94

95

DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What are the photosynthetic organisms on the planet, and why are they so important?

- What are the different types of energy and what transformations of energy do organisms carry out?

- How do plants and algae convert the energy in sunlight into energy-rich organic molecules? (And why can’t humans do this?)

- How do algal biofuels compare to other fuels in terms of costs, benefits, and sustainability?

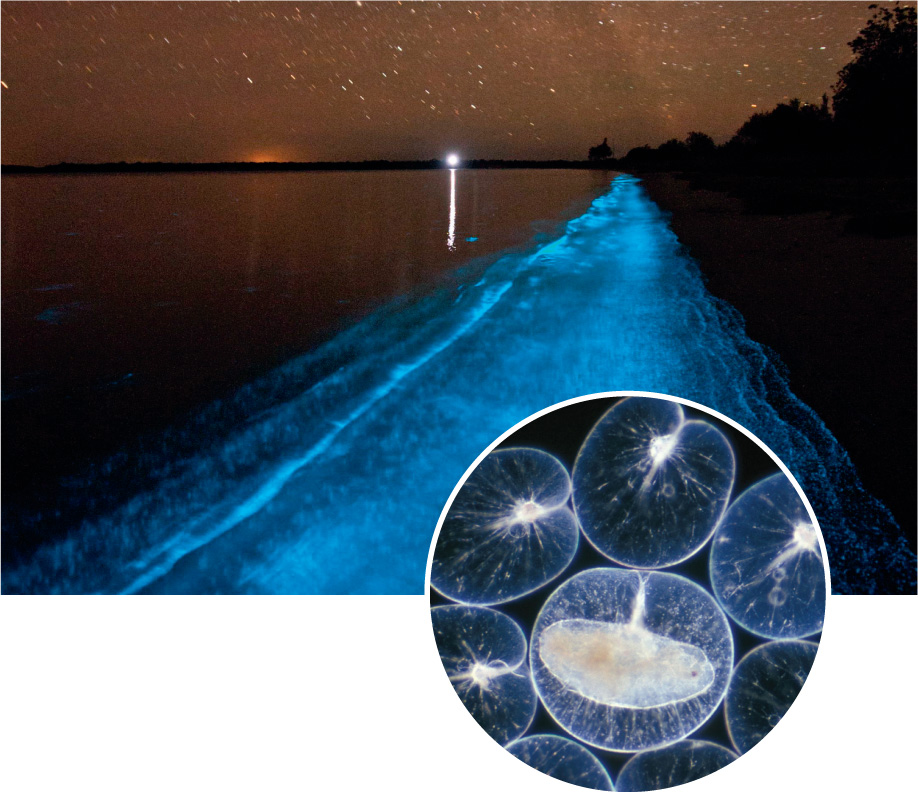

S AN ENGINEER WORKING FOR the Navy Seals in 1978, Jim Sears took a nighttime scuba dive off the coast of Panama City, Florida–one of many he took to do underwater research. The dive started out routinely, but then, suddenly, glowing phosphorescent algae appeared as if out of nowhere. When Sears put his hands out in front of him, sparkling streamers of microbes came off his fingertips. “It was magical,” he recalls.

S AN ENGINEER WORKING FOR the Navy Seals in 1978, Jim Sears took a nighttime scuba dive off the coast of Panama City, Florida–one of many he took to do underwater research. The dive started out routinely, but then, suddenly, glowing phosphorescent algae appeared as if out of nowhere. When Sears put his hands out in front of him, sparkling streamers of microbes came off his fingertips. “It was magical,” he recalls.

Sears is an inventor with many and varied devices to his credit. When working for the Navy in the 1970s and 1980s, he built an underwater speech descrambler and a portable mine detector, among other things. Later he moved on to more creative ventures, including a “hump-o-meter” that could tell farmers when their animals were in heat or mating.

96

But the seeds of his real claim to fame weren’t sown until 2004, when Sears was working on agricultural electronics. That’s when he began to turn his attention toward what he felt was the world’s biggest problem: dwindling fossil fuel reserves. After he did some thinking and a little research, the tiny, glowing organisms that had wowed him during his dive more than two decades earlier came to mind, in part because of a website he stumbled across that discussed the unique properties of algae. He realized suddenly that they might be able to help.

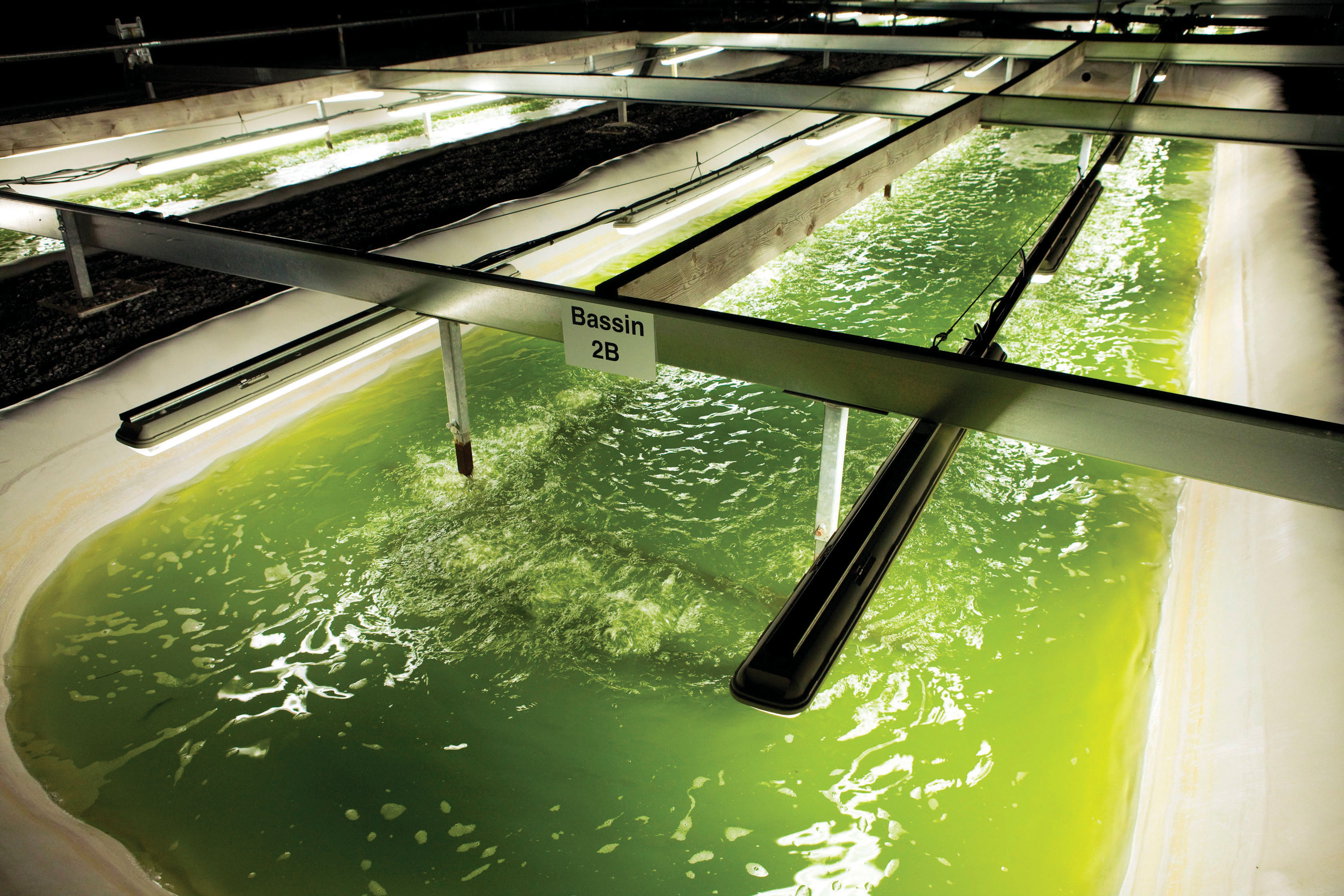

Algae are perhaps best known for the green, red, or brown hues they give to the surfaces of ponds and swimming pools, but they have other unique characteristics, too. The evolutionary ancestors of plants, algae were among the first eukaryotic life forms to appear on our planet. There are large multicellular forms, like seaweed, and microscopic single-cell forms called microalgae. Both types share with green plants the impressive ability to capture the energy of sunlight and convert it into forms of energy usable by other organisms. Even more remarkable, much of that usable energy is in the form of oils ideally suited to making fuel. The oil that microalgae produce is very similar to common vegetable oil. It accumulates inside the microbes’ tiny cells, and once extracted, it can be processed to make biodiesel, gasoline, or jet fuel. “The more I looked into them, the more amazing they were,” Sears says.

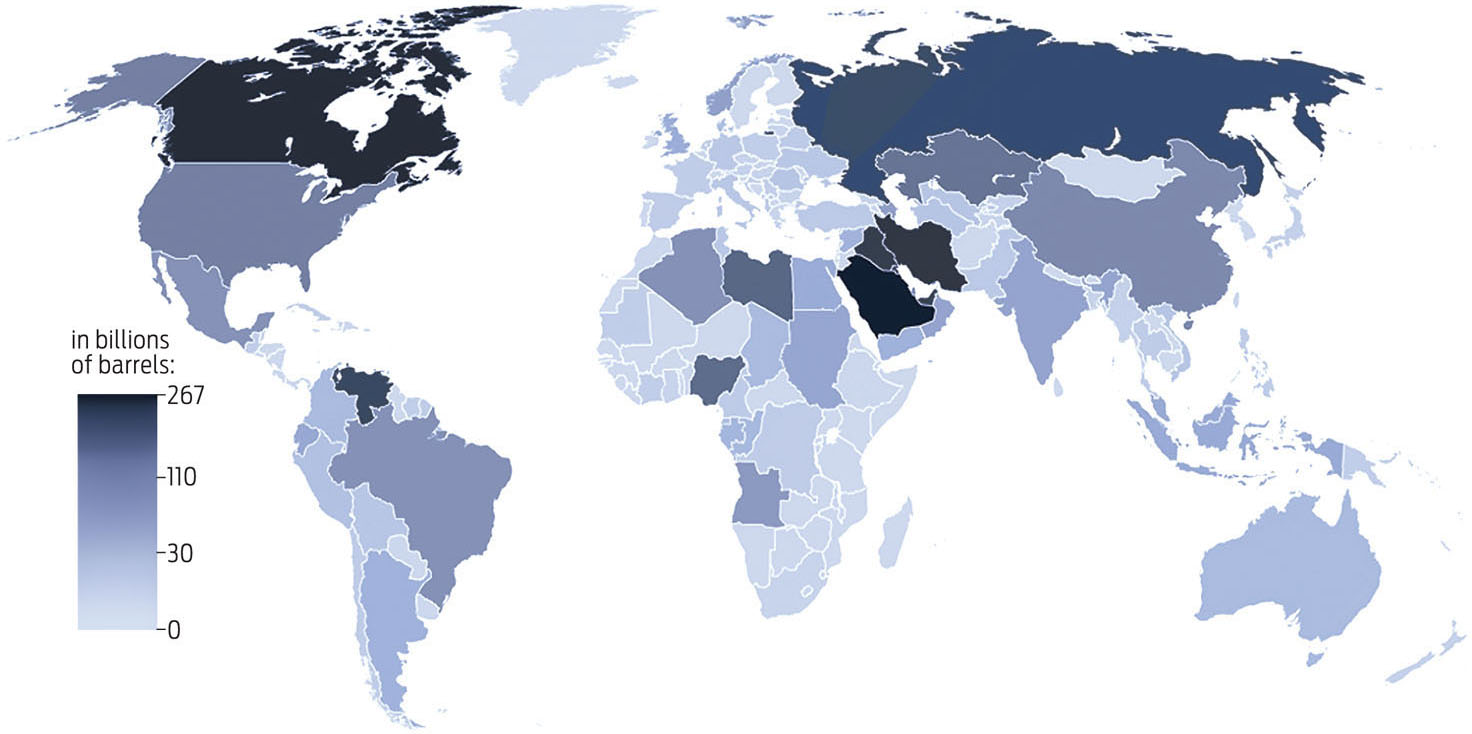

And that’s good news, because America is desperate for new fuels. After all, Americans burn through 378 million gallons of gasoline a day, enough to fill about 540 Olympic-size swimming pools. And despite the fact that our demand will likely increase over the course of the next 25 years, the sources of our precious gasoline—oil reserves buried deep underground—are finite, take millions of years to replenish, and largely lie outside U.S. borders (INFOGRAPHIC 5.1) .

The gasoline used to power cars begins as oil formed deep in the ground over millions of years. The United States depends heavily on oil recovered from other countries for its fuel supply.

97

BIOFUELS Renewable fuels made from living organisms (e.g., plants and algae).

Confronted with this looming crisis, scientists and politicians are now turning toward alternatives such as biofuels—renewable fuels made from living organisms. In an effort to end our addiction to oil, in 2007 President George W. Bush signed the Energy Independence and Security Act, which requires the United States to produce 36 billion gallons of renewable fuels by 2022, of which 21 billion gallons must be advanced biofuels (and not corn-based ethanol).

Convinced of the promise of algae biofuels, in 2006, Sears founded Solix, one of the first biotechnology companies working to mass-produce biodiesel from algae. Though he is no longer involved with Solix, the company is still going strong. In 2009, it began commercially producing its algae-based fuel, with the goal of making the equivalent of 3,000 gallons of oil per acre of cultivated algae. Other companies are getting on the algae bandwagon—as of 2012, there were more than 150 companies dedicated to making fuel from algae. In January 2009, Continental Airlines flew its first plane powered in part by jet fuel made from algae. In September of that year, a modified Toyota Prius dubbed Algaeus drove 3,750 miles across the country powered by a fuel mix of algal and conventional gasoline, plus batteries. And in November 2012, California gas stations began pumping algae-derived biodiesel. Algae, many say, are the fuel source of the future.

Americans burn through 378 million gallons of gasoline a day, enough to fill about 540 Olympic-size swimming pools.

Americans burn through 378 million gallons of gasoline a day, enough to fill about 540 Olympic-size swimming pools.