Curbing Culture

Given the relationship between Calorie intake and our expanding waistlines, many people are interested in altering the way we eat to reduce the amount of Calories that make it into our bloodstream. Food industry scientists, for example, have developed diet drugs that keep the body from absorbing some of the fat molecules in food. (You may have heard of potato chips made with olestra, a fat substitute that is not absorbed by the intestines and so passes through the body as waste, with famously unpleasant effects.) And, of course, many food manufacturers specialize in low-fat and fat-free foods, which are less Calorie dense.

But these efforts to curb obesity offer temporary solutions at best. Studies have shown that 90% of dieters regain most of their lost weight within 2 to 3 years. That’s because most people find it terribly difficult to stick to the food restrictions prescribed by diets and tend to revert to their former eating habits. And in some cases, losing weight actually makes people hungrier, and hunger is one of the most powerful biological signals.

A change in eating culture, say some experts, offers a more sustainable fix because it emphasizes a change in eating habits, not the type of food itself. In fact, Americans didn’t always consume large portion sizes. Lisa Young and Marion Nestle, both of the Department of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University, documented in a 2002 study that the current sizes of fries, hamburgers, and soda at restaurants were two to five times larger than they were before the 1970s, when portion size began to creep up. Single servings of pasta, muffins, steaks, and bagels today exceed the government-recommended serving sizes by 480%, 333%, 224%, and 195%, respectively. And cookies exceed the standard by a factor of 8, according to Nestle’s research. In America, bigger is better.

130

TRANS FAT A type of vegetable fat that has been hydrogenated, that is, hydrogen atoms have been added, making it solid at room temperature.

The French are eating more, too, and the results are evident: the number of obese French people grew from 8.6% in 1997 to 13.1% in 2006, according to a 2008 study by Marie-Aline Charles published in the journal Obesity. As American music, movies, and clothing have become pervasive in other countries, so, too, have our eating habits. More and more French people are eating large amounts of nutritionally poor, energy-dense foods. And as jobs increasingly place people in front of computers, they have become less physically active. More French people are eating on the go, eating fast food, and spending less time enjoying formal meals. Much to the dismay of public health experts, French eating culture is tipping toward unhealthful.

SATURATED FAT An animal fat, such as butter; saturated fats are solid at room temperature.

Meanwhile, studies suggest that the rate of obesity in the United States may be leveling off. A 2010 study by Katherine Flegal at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found no significant increase in the rate of obesity in the United States from 2003 through 2008. Nevertheless, at 30% the prevalence of obesity in the United States is still high and remains higher than in most European countries (and more than double the prevalence in France).

UNSATURATED FAT A plant fat, such as olive oil; unsaturated fats are liquid at room temperature.

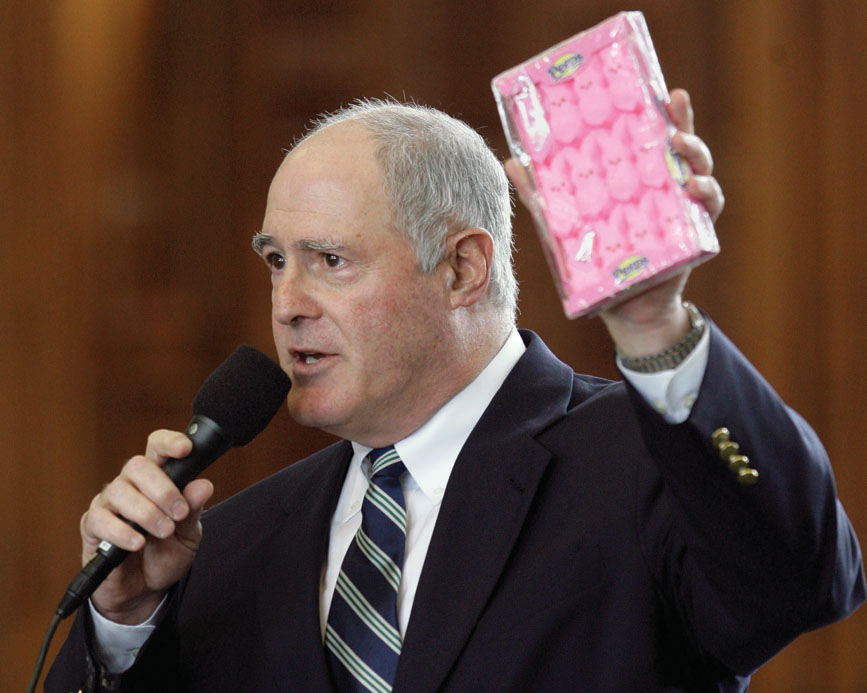

Because of this statistic, there is a growing trend in the United States to legislate changes in the foods people eat. Some cities, for example, have banned the use of trans fat, a type of hydrogenated vegetable fat that studies have shown contributes to heart disease. Commercially prepared cookies, French fries, doughnuts, and margarine often contain trans fat, which food manufacturers add to their products to give them a longer shelf life or a pleasing texture. Hydrogenated fat behaves in the body much like saturated fat, the type of fat found in butter and other animal products. Studies have shown that eating large amounts of saturated fat can clog arteries (see Chapter 27). By contrast, unsaturated fats, which come from plants and are liquid at room temperature, are considered more healthful (although they are still high in Calories). In New York City, restaurants are now required to post their foods’ Calorie content, and in 2012, Mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed a ban on the sale of sugary beverages larger than 16 ounces in restaurants, from street carts, and in movie theaters in the city.

131

Studies have shown that 90% of dieters regain most of their lost weight within 2 to 3 years.

“Actions by governments are the only way conditions will change enough to have a major public health impact,” says Kelly Brownell. For America’s obesity woes, Brownell blames the food industry for its relentless marketing of unhealthful foods, agricultural and trade policies that promote unhealthful diets, and economic policies that make unhealthful foods cheaper than healthful ones.

Not everyone agrees, however, that it is the government’s job to restrict our food choices. Americans equate choice in food with democracy, argues Paul Rozin. “We could also over-respond to what many perceive as an obesity epidemic and that could be dangerous. It would restrict individual freedom.”

Besides, while such government legislation would restrict what we eat, it wouldn’t really affect how we eat. Rozin hopes people change their behavior voluntarily. For example, people could fit more movement into their daily routines, climbing stairs instead of using an elevator or parking their cars farther away from the entrance to the mall. To combat large portion sizes in restaurants, Rozin advocates ordering less, sharing dishes, or, as Mireille Guiliano recommends, relearning how to savor our food.

The U.S. eating culture can change, Rozin says, but not overnight. Look at cigarette smoking: “It took 50 years to get cigarette smoking to decline and [cigarettes] are much more harmful to health.”

132