Y-Chromosome Analysis

Y-CHROMOSOME ANALYSIS Comparing sequences on the Y chromosome to examine paternity and paternal ancestry.

Did Thomas Jefferson father children with a slave?

Did Thomas Jefferson father children with a slave?

ANSWER: Thomas Jefferson was the third president of the United States, the principal architect of the Declaration of Independence, and founder of the University of Virginia. He was also a slave holder. Historians have long debated the meaning of this and other seeming contradictions in the founding father’s life and politics. For example, although Jefferson’s writings clearly show that he did not believe in the institution of slavery, he owned at least 200 slaves. He made disparaging comments about slaves, yet maintained close relationships with those living in his house.

In some cases, very close. Jefferson was rumored to have fathered at least six children with Sally Hemings, a slave who tended to his family. For decades, historians discredited the rumor as unreliable oral history. In 1998, scientists attempted to find out by testing the DNA of both Hemings’s and Jefferson’s descendants with a technique called Y-chromosome analysis.

Y-chromosome analysis is commonly used to study ancestry and to identify paternity. It is just one of several ways in which science can complement history. Scientists can use Y-chromosome analysis to verify or discredit accepted history, or to fill in missing pieces of historical information.

During Jefferson’s own time, people commented on the resemblance of Hemings’s children to the president.

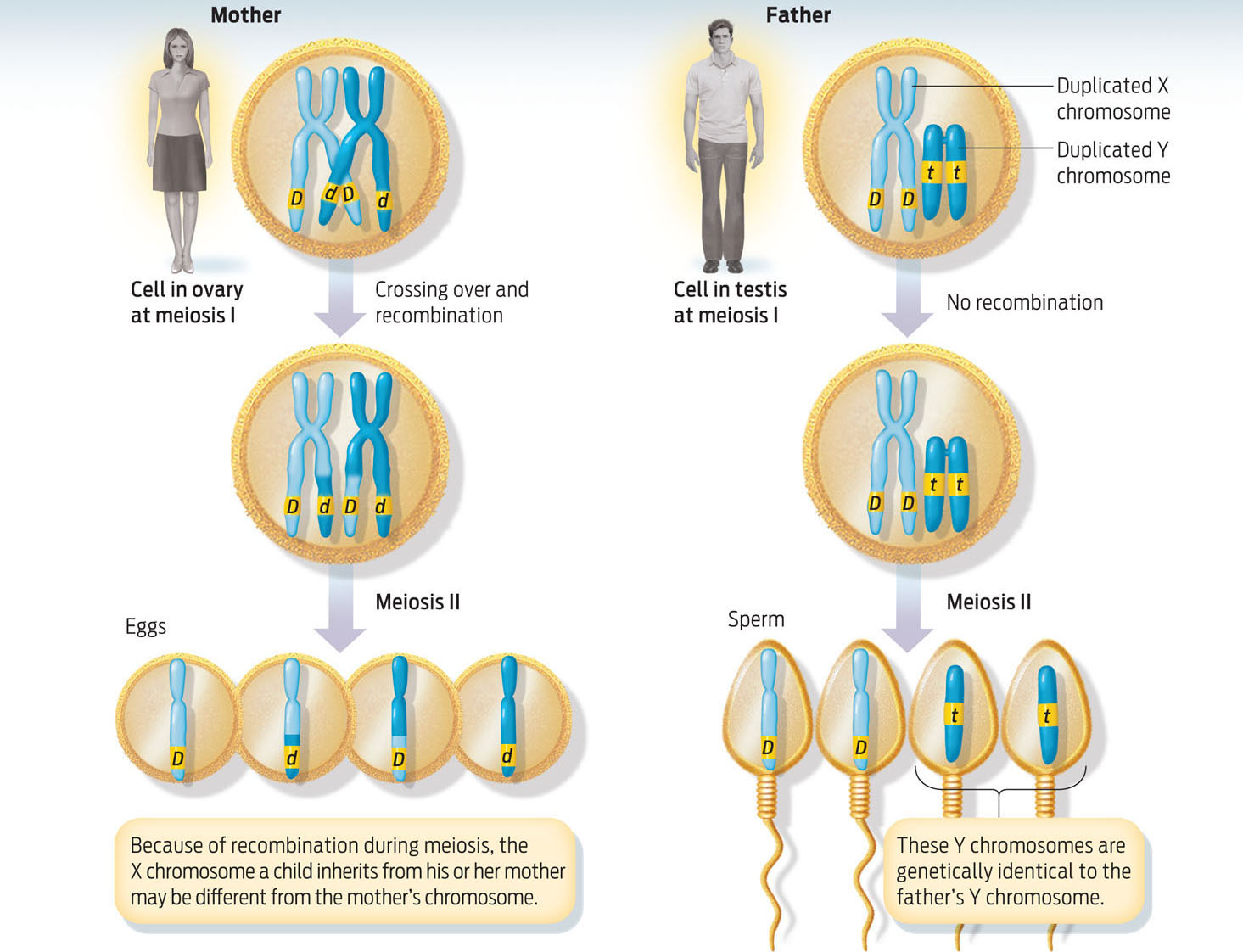

How does Y-chromosome analysis work? As the name implies, in this technique researchers examine the Y-chromosome, which is very small and contains few genes. Sons inherit their Y chromosome from their fathers. These Y chromosomes are passed through generations, from fathers to sons, largely unchanged. That’s because Y chromosomes have no homologous partner chromosome with which to pair and exchange DNA during meiosis (see Chapter 11). In other words, the Y chromosome rarely undergoes genetic recombination. Consequently, the Y chromosome that a son inherits from his father is almost identical to the Y chromosome that his father inherited from his father (INFOGRAPHIC 12.4).

Y-chromosome analysis for paternity testing relies upon the fact that the Y chromosome does not undergo recombination during meiosis and so passes unchanged from the father to his sons.

Comparing DNA sequences on Y chromosomes can reliably establish paternity and help to establish a line of ancestry. For example, scientists have used Y-chromosome analysis to show that 90% of the Cohanim—members of the historic Jewish priesthood—are related, supporting oral and written histories claiming the Cohanim (the Hebrew plural from which we derive the name “Cohen”) are all descended from Aaron, brother of Moses. They’ve also used Y-chromosome analysis to support the oral history of the Lemba, an African tribe, who claim they are descended from Jews. And Y-chromosome analysis suggests that about 8% of Eastern European and Asian men are descended from Genghis Khan or his family.

During Jefferson’s own time, people commented on the resemblance of Hemings’s children to the president. But later historians either explained the resemblance away or proposed other explanations—for example, that one of Jefferson’s nephews had fathered her children.

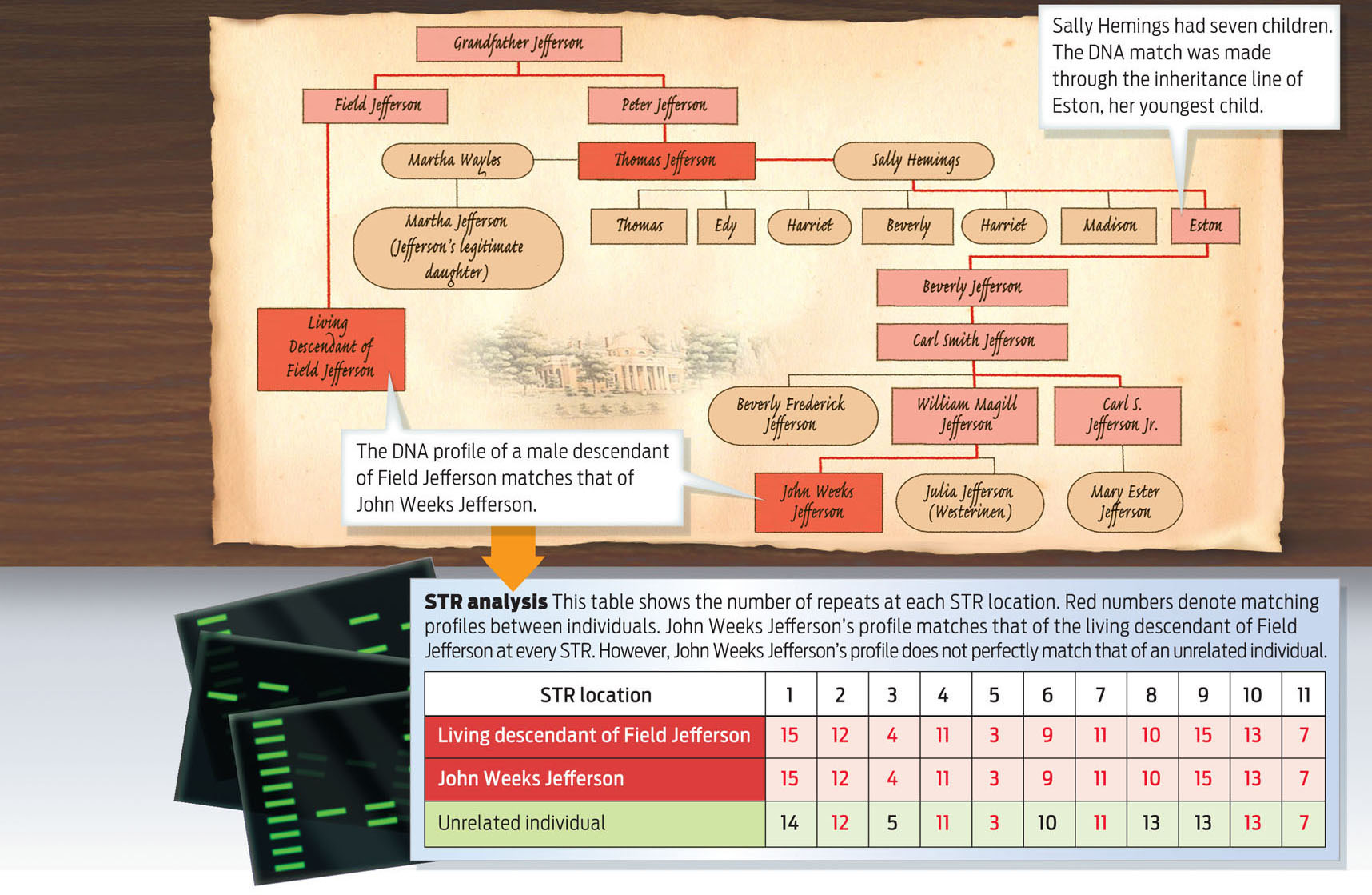

To set the record straight, in 1998 a team of geneticists led by Eugene A. Foster compared the Y chromosomes of three groups of men: descendants of Thomas Jefferson’s paternal uncle Field Jefferson; one male descendant of Eston Hemings, Sally Hemings’s son; and descendants of Jefferson’s sister’s sons. Since Jefferson’s only surviving child from his wife was a daughter, he did not have any direct male descendants, which is why scientists tested descendants of Jefferson’s uncle.

The team analyzed 11 short tandem repeats (STRs) on the Y chromosome. (Recall from Chapter 7 that STRs are short regions of DNA that are repeated a different number of times in different people, and are used in DNA profiling.) They made some startling discoveries: the results clearly showed that descendants of Thomas’s nephews have a different Y chromosome from the man descended from Eston Hemings, thus ruling out Thomas’s nephews as the father of Sally’s children. The results also clearly showed that Eston’s descendant—John Weeks Jefferson—has the same Y chromosome as the descendants of Field Jefferson. Consequently, Thomas Jefferson could have fathered Eston Hemings. The study does not prove that he is the father, but it does show that the father was definitely a male Jefferson (INFOGRAPHIC 12.5).

Scientists compared DNA sequences on the Y chromosome of Sally Hemings’s and Thomas Jefferson’s grandfather’s descendants. The DNA sequences match at the 11 different STR locations analyzed.

Some historians have argued that Thomas’s younger brother Randolph Jefferson could have fathered Eston. (Or, indeed, that any of the other seven Jefferson males who periodically visited Monticello, where Thomas and Sally lived, could be the father.) But other experts have argued that historical evidence—for example, records of the president’s travels—place him rather than Randolph under the same roof as Sally at the time of her conceptions. A 2000 report by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation concludes that the preponderance of historical and biological evidence points to a “strong likelihood” of a sexual relationship between Thomas and Sally.

For the descendants of Eston Hemings, the DNA study was powerful vindication, even if debate continues. They had long argued that they were descended from Thomas Jefferson, but without hard evidence, most historians disregarded their claims. “I feel wonderful about it,” Julia Jefferson Westerinen, a Staten Island artist and Eston’s great-great-granddaughter told the New York Times when the study results were published. “I feel honored.”

As for the relationship between Jefferson and Sally Hemings, historians continue to debate whether it was consensual or forced. “I was a history major,” said Jefferson Westerinen, “And we learned not to say, ‘I feel this, I think that,’ without knowing the facts. They had a relationship of 38 years. I would like to think they were in love, but how would I know?”

We’ll likely never know the truth. Neither Thomas Jefferson nor Sally Hemings left any written evidence of their relationship.