DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- How does the fossil record reveal information about evolutionary changes?

- What features make Tiktaalik a transitional fossil, and what role do these types of fossil play in the fossil record?

- What can anatomy and DNA reveal about evolution?

In-Class Activity

Click here to access Lecture ppt specifically designed for chapter 16.

Click here to access Clicker Questions specifically designed for chapter 16.

OR 5 YEARS, BIOLOGISTS NEIL SHUBIN AND TED DAESCHLER spent their summers trekking through one of the most desolate regions on Earth. They were fossil hunting on remote Ellesmere Island, in the Canadian Arctic, about 600 miles from the north pole. Even in summer, Ellesmere is a forbidding place: a windswept, frozen desert where sparse vegetation grows no more than a few inches tall, where sleet and snow fall in the middle of July, and where the sun never sets. Only a handful of wild animals survive here, but those that do make for dangerous working conditions: hungry polar bears and charging herds of muskoxen are known hazards of working in the arctic, says Daeschler, who carried a shotgun for protection.

OR 5 YEARS, BIOLOGISTS NEIL SHUBIN AND TED DAESCHLER spent their summers trekking through one of the most desolate regions on Earth. They were fossil hunting on remote Ellesmere Island, in the Canadian Arctic, about 600 miles from the north pole. Even in summer, Ellesmere is a forbidding place: a windswept, frozen desert where sparse vegetation grows no more than a few inches tall, where sleet and snow fall in the middle of July, and where the sun never sets. Only a handful of wild animals survive here, but those that do make for dangerous working conditions: hungry polar bears and charging herds of muskoxen are known hazards of working in the arctic, says Daeschler, who carried a shotgun for protection.

VERTEBRATE An animal with a bony or cartilaginous backbone.

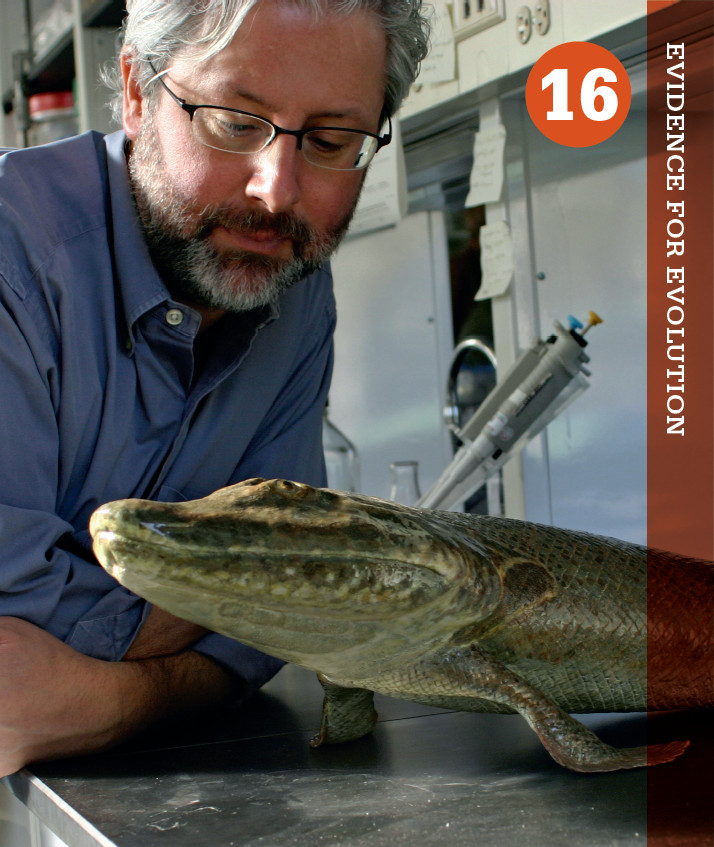

When not looking over their shoulders, the researchers drilled, chiseled, and hammered their way through rocks looking for fossils. Not just any rocks and fossils, but ones dating from 375 million years ago, when animals were taking their first tentative steps on land. For three summers, they scoured the site of what was once an active streambed but found little of interest. Then, in 2004, the team made a tantalizing discovery: the snout of a curious-looking creature protruding from a slab of pink rock. Further excavation revealed the well-preserved remains of several flat-headed animals between 4 and 9 feet long. In some ways, the animals resembled giant fish—they had fins and scales. But they also had traits that resembled those of land-dwelling amphibians—notably, a neck, wrists, and fingerlike bones. The researchers named the new species Tiktaalik roseae; tiktaalik (pronounced tic-TAH-lick) is a native word meaning “large freshwater fish.” This ancient hybrid animal no longer exists, but it represents a critical phase in the evolution of four-legged, land-dwelling vertebrates—including humans.

Tiktaalik “splits the difference between something we think of as a fish and something we think of as a limbed animal,” says Daeschler, a curator of vertebrate zoology at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. “In that sense, it is a wonderful transitional fossil between two major groups of vertebrates.”

Today, of course, four-legged animals roam far and wide over land. But 400 million years ago it was a different story. Life was mostly aquatic then, restricted to oceans and freshwater streams. How life made the jump from water to land is a question that has long intrigued evolutionary biologists. In fact, scientists have been searching for evidence of this milestone ever since Charles Darwin first proposed that all life on the planet is related by a tree of common descent. According to Shubin, a professor of biology at the University of Chicago and the Field Museum of Natural History, Tiktaalik is the most compelling example yet of an animal that lived at the cusp of this important transition. Not only does it fill a gap in our knowledge, the discovery also provides persuasive evidence in support of Darwin’s theory.

Tiktaalik “splits the difference between something we think of as a fish and something we think of as a limbed animal.

Tiktaalik “splits the difference between something we think of as a fish and something we think of as a limbed animal.

— TED DAESCHLER