THE FOSSIL HUNT

Shubin and Daeschler began their hunt for fossils in the Canadian Arctic in 1999, after stumbling upon a map in an old geology textbook. The map showed that the region contained large swaths of exposed rock dating back 375–380 million years—just the period of time the researchers were interested in.

Why was this period so important to the scientists? They knew that there are no land-dwelling vertebrates in the fossil record before 385 million years ago. By 365 million years ago, organisms easily recognizable as amphibians are well documented in the fossil record. The scientists hypothesized that if they looked at rocks sandwiched in between these two time periods—around 375 million years old—they might find one of Darwin’s elusive “intermediates.” Moreover, Ellesmere is one of only three places on Earth where rocks of this time period are exposed, yet to Shubin and Daeschler’s knowledge, no other paleontologists had explored the area, which meant it was a potential fossil gold mine.

Knowing exactly where to look for fossils was tricky, since Ellesmere Island covers 75,000 square miles. To locate the most promising dig site, the scientists first studied aerial photographs. Once on the ground, the scientists and their team split up and spent the first two seasons just walking the rocky exposures, prospecting for bits and pieces of fossils that had eroded out from the rock. When they found something interesting on the surface, they would start to dig.

It was while walking these rocky exposures in 2002 that Daeschler and his team found the first piece of what would turn out to be a Tiktaalik fossil—“basically part of the snout,” he says. At first, they didn’t think much of the find, but collected it anyway along with other fossil pieces. Back in Philadelphia, researchers cleaned the fossil, removing the remaining rock. Even then, says Daeschler, it wasn’t clear what the snout belonged to. Not until a visiting graduate student remarked on the resemblance of the skull to one from the earliest known amphibians did the researchers realize what they had found. If ever there was a “lightbulb” moment, he says, this was it. But, alas, they had only one small piece of the creature.

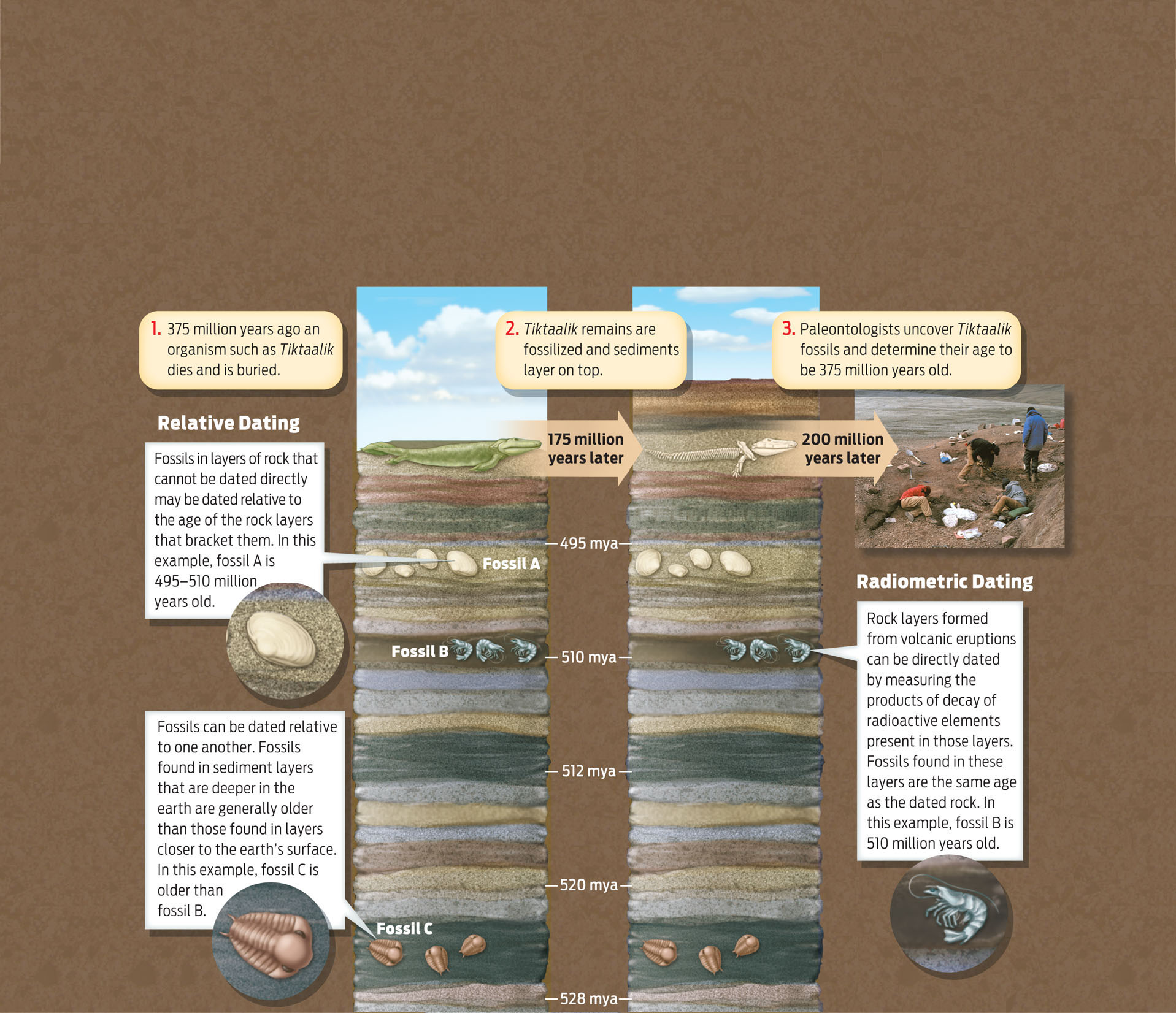

RADIOMETRIC DATING The use of radioactive isotopes as a measure for determining the age of a rock or fossil.

The team returned to Ellesmere in 2004 for another round of hunting and digging. It didn’t take long for their patience to be rewarded: “Literally inches,” Daeschler says, from where they’d been excavating before, they hit pay dirt.

RELATIVE DATING Determining the age of a fossil from its position relative to layers of rock or fossils of known age.

The fossils they found looked like the elusive intermediate creature the team had been hunting for. But how could they be sure it was the right age? Logically, fossils are at least as old as the rocks that encase them, so if you know the age of the rocks, then you know the age of the fossils, too. Some types of rocks can be dated directly by a method known as radiometric dating, which uses the proportion of certain radioactive isotopes in rock crystals as a geologic clock (see Chapter 17). Fossils found in or near these layers can be dated quite precisely. If fossils are found in rock layers that cannot be directly dated, they can be dated indirectly by their position with respect to rocks or fossils of known age, either deeper or shallower, a technique called relative dating. Generally speaking, the deeper the fossils, the older they are. Using a combination of both methods, scientists have determined that the rocks where Tiktaalik was found are 375 million years old, which means Tiktaalik is that old as well (INFOGRAPHIC 16.3).