DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What are the prokaryotic domains of life?

- What are the features of bacteria and of archaea?

- What are the challenges faced by organisms living at Lost City, and how do they face them?

In-Class Activity

Click here to access Lecture ppt specifically designed for chapter 18.

Click here to access Clicker Questions specifically designed for chapter 18.

RETCHEN FRÜH-GREEN’S HEART HAD NEVER BEAT SO fast. Late on a December evening in 2000, she was hunkered down in the control room of the research ship Atlantis, monitoring live video streaming up to the ship from a camera swimming half a mile below. Strange white shapes began to appear in the blackness of her screen. As the camera panned, an underwater landscape of ghostly white towers suddenly came into focus. The huge limestone structures, which resembled the stalagmites found in caves, loomed above an otherwise empty seafloor. Früh-Green, a geologist with the Institute for Mineralogy and Petrology in Zurich, Switzerland, knew immediately that she was looking at something special and raced to tell her colleagues. “It was really quite exciting,” she said. “It was late at night and kind of woke us all up.”

RETCHEN FRÜH-GREEN’S HEART HAD NEVER BEAT SO fast. Late on a December evening in 2000, she was hunkered down in the control room of the research ship Atlantis, monitoring live video streaming up to the ship from a camera swimming half a mile below. Strange white shapes began to appear in the blackness of her screen. As the camera panned, an underwater landscape of ghostly white towers suddenly came into focus. The huge limestone structures, which resembled the stalagmites found in caves, loomed above an otherwise empty seafloor. Früh-Green, a geologist with the Institute for Mineralogy and Petrology in Zurich, Switzerland, knew immediately that she was looking at something special and raced to tell her colleagues. “It was really quite exciting,” she said. “It was late at night and kind of woke us all up.”

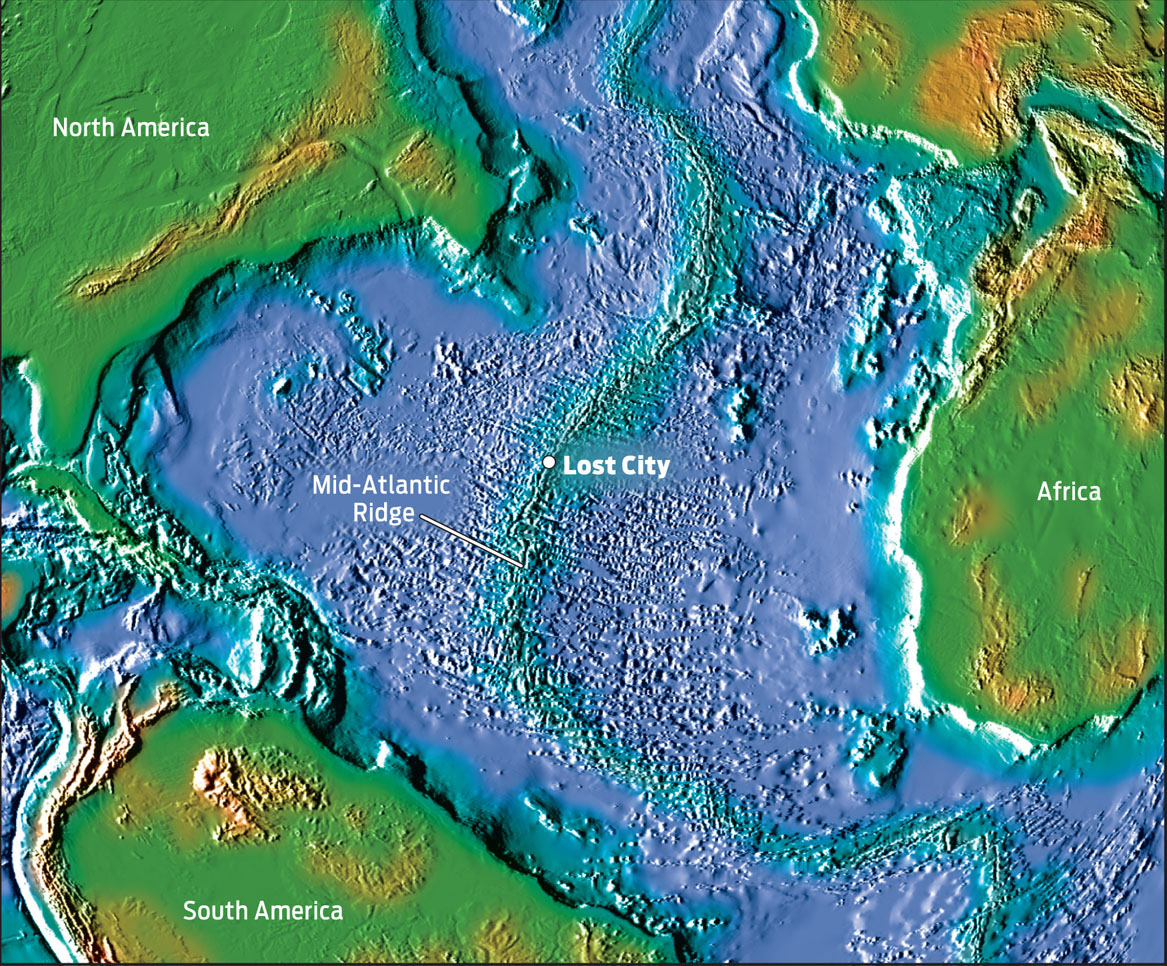

The next day, the mission’s chief scientist, Deborah Kelley, and two members of the team climbed into a submersible craft that dived 2,600 feet down to the site, which sits on an undersea mountain in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. There they found a dense “cityscape” of rocky spires, stretching across roughly six football fields of dark seafloor. It was an uncharted world no one had known existed. Kelley named the undersea world “Lost City.” The tallest tower, measuring 200 feet, she dubbed “Poseidon,” after the Greek god of the sea.

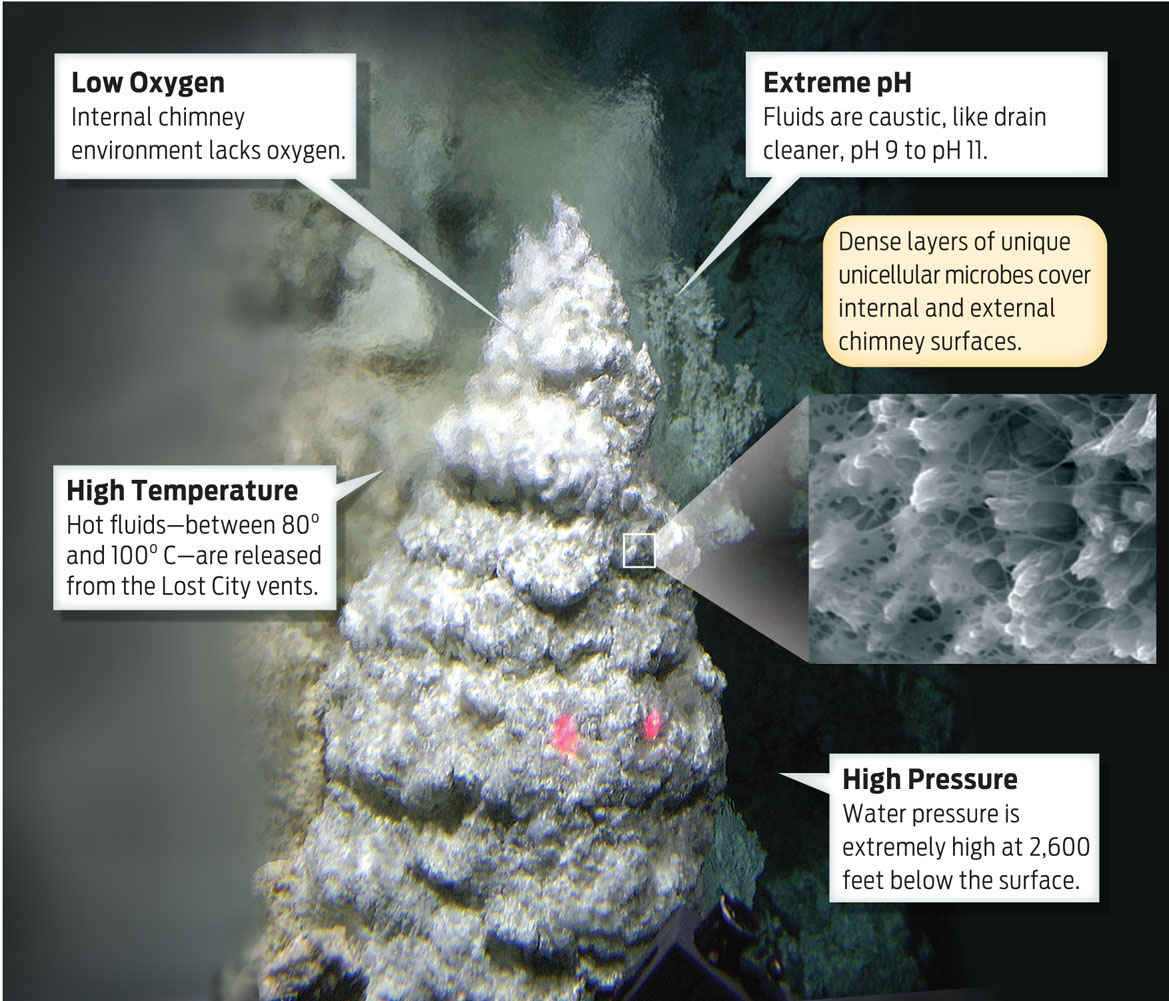

Subsequent research has shown that each tower is a type of underwater chimney, or spring, known as a hydrothermal vent. As rocks beneath Earth’s crust come in contact with seawater, they react chemically, giving off a steady stream of heat and combustible gas that seeps out of each vent. The resulting fluid is highly caustic, with a pH of 9 to 11—similar to that of drain cleaner—and temperatures as hot as 100°C (212°F).

Though deep-sea hydrothermal vents had been discovered before, the ones at Lost City were unique in their chemistry and in the type of life they support. Nothing like them had ever been seen. “Rarely does something like this come along that drives home how much we still have to learn about our own planet,” said Kelley, an oceanographer at the University of Washington in Seattle, who now leads the international team of scientists who are exploring Lost City’s mysteries.

An extreme and seemingly inhospitable environment, the towers of Lost City are nonetheless home to a surprising number of life forms. The most prevalent living creatures are dense layers of unicellular microbes that coat the towers, inside and out (INFOGRAPHIC 18.1). Microbial life exists pretty much everywhere on Earth—in frozen glaciers, in radioactive dirt, in the intestines of animals—yet the microbes at Lost City have earned the fascination of scientists.

The hydrothermal vents of Lost City are huge rock chimneys. Scalding fluid with an extremely basic pH flows out of the tops of these chimneys. The towering size and range of environments within and around a single Lost City spire mean it can host a variety of unique microbial communities.

“They’re living in boiling toilet bowl cleaner full of flammable gas,” says Bill Brazelton, a postgraduate researcher with NASA and the University of Washington, who studies the microbes. The extreme conditions of this environment resemble what researchers think the ancient Earth was like, some 3.8 billion years ago, when life was getting started. Scientists have long wondered how life managed to emerge and flourish in such inhospitable conditions. At Lost City, they are finding some tantalizing clues.