THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON CAFFEINE

Caffeine is a stimulant. It is in the same class of psychoactive drugs as cocaine, amphetamines, and heroin (although less potent than these, and acting through different mechanisms). Caffeine boosts not just memory and mental performance but physical performance as well. Sports physiologists agree that consuming caffeine before a workout can boost stamina—a fact that is no secret among athletes. A 2004 study found that 33% of 193 track and field athletes and 60% of 287 cyclists said they consumed caffeine to enhance their performance. Recognizing that caffeine is a performance-enhancing drug, the International Olympic Committee prohibited athletes from using it until 2004 (when the committee decided to allow it, presumably because it had become too common a substance to regulate).

While the exact mechanisms are not fully understood, scientists think that caffeine exerts its energizing effect primarily by counteracting the actions of a chemical in the brain called adenosine, which is a type of neurotransmitter. Adenosine is the body’s natural sleeping pill—its concentration increases in the brain while we are awake and by the end of the day promotes drowsiness. Caffeine blocks the effect of adenosine in the brain, thereby delaying fatigue and keeping us more alert.

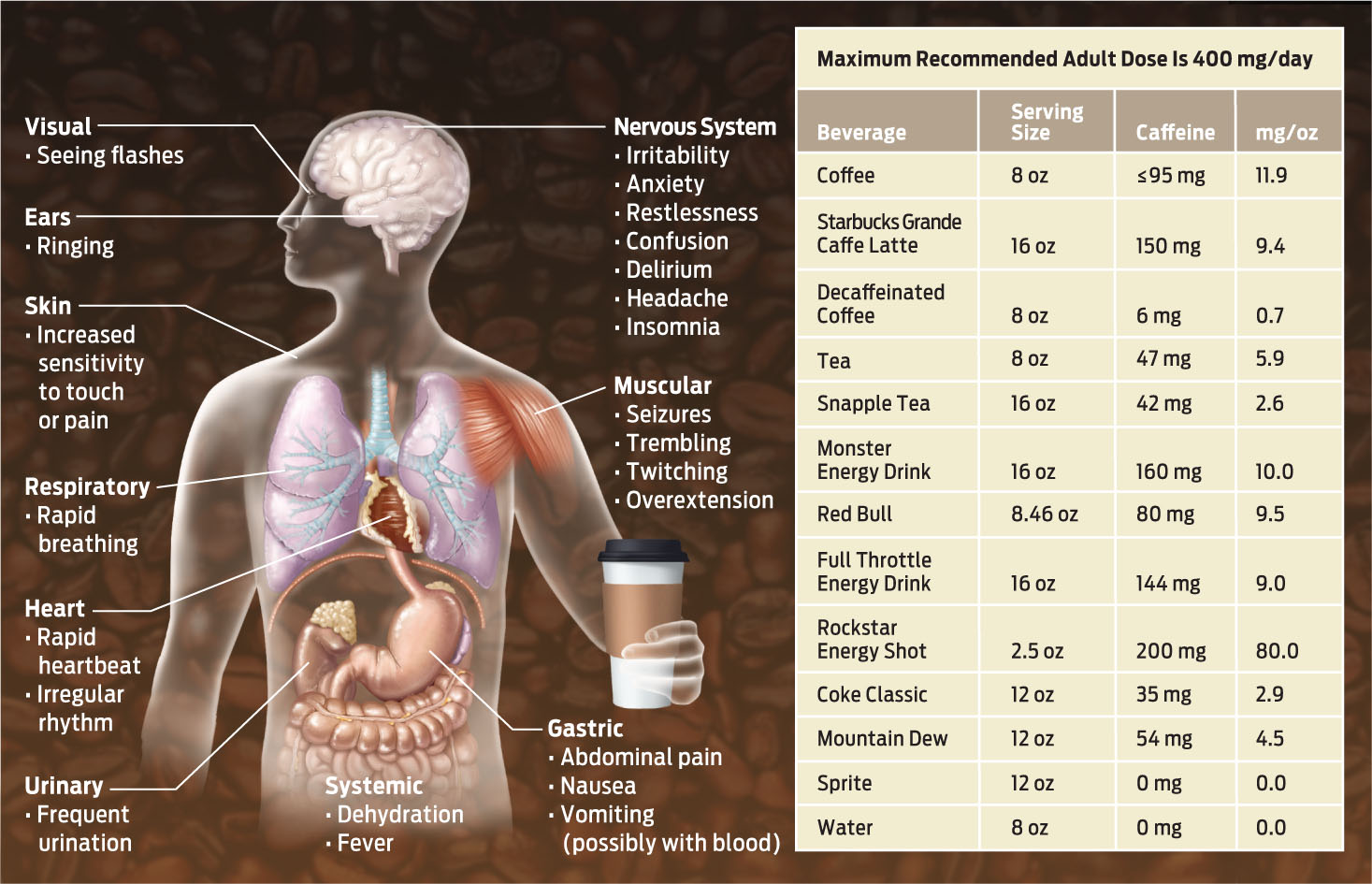

Consumption of caffeinated beverages has skyrocketed in the past 25 years, especially among young people. A 2009 study in the journal Pediatrics found that teenagers in a Philadelphia suburb consume anywhere from 23 mg to 1,458 mg of caffeine a day—the equivalent of nearly 10 cups of coffee, and more than three times the recommended safe dose for an adult of 400 mg/day or less. In excess, caffeine can cause anxiety, jitters, heart palpitations, trouble sleeping, dehydration, and more serious symptoms as well—especially in people who are sensitive to it. Of the 4,852 caffeine overdoses reported to poison control centers in the United States in 2008, 49% occurred in those younger than 19, according to a 2011 study in Pediatrics. In 2012, a 14-year-old Maryland girl died of cardiac arrhythmia after drinking two 24-ounce Monster Energy drinks (240 mg of caffeine each) in a 24-hour period, prompting U.S. Senator Dick Durbin to call for greater federal oversight of energy drinks (INFOGRAPHIC 1.6).

Despite potential benefits as a memory-enhancer, the caffeine in coffee has some powerful side effects.

For regular coffee drinkers who crave their morning buzz, such side effects are unlikely to persuade them to kick the habit. This may be because, like many other psychoactive substances, caffeine is addictive. Those who drink a significant amount of coffee every day may notice that they don’t feel quite right if they skip a day; they may be cranky or get a headache. These are symptoms of withdrawal. In fact, some researchers contend that coffee’s mind-boosting effects are an indirect result of the cycle of dependency. Improvement in mood or performance following a cup of coffee, they say, may simply represent relief from withdrawal symptoms rather than any specific beneficial property of coffee.

To test this dependency hypothesis, scientists could conduct an experiment. They could compare the effects of drinking coffee in two groups: one group of regular coffee drinkers who had abstained from coffee for a short period, and another group of non-coffee drinkers. Does coffee give both groups a boost, or only the regular coffee drinkers looking for their fix?

This very experiment was done in 2010 by a group of researchers at the University of Bristol in England. Their study, published in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, looked at caffeine’s effect on alertness. Researchers gave caffeine or a placebo to 379 participants and asked them to take a test that rated their level of alertness. The study found that caffeine did not boost alertness in non-coffee drinkers compared to those drinking a placebo (although it did boost their level of anxiety and headache). Heavy coffee drinkers, on the other hand, experienced a steep drop in alertness when given the placebo.

“What this study does is provide very strong evidence for the idea that we don’t gain a benefit in alertness from consuming caffeine,” the study author, Peter Rogers, said. “Although we feel alert, that’s just caffeine bringing us back to our normal state of alertness.”

For those of us who rely on coffee to perk us up, the results of this one study are unlikely to change our minds—or our habits. Yet even if confirmed, these results don’t really explain why people get hooked on coffee in the first place.