DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What contributes to human skin color, and why is there so much variation in skin color among different populations?

- Where did the earliest humans evolve, and how do we know?

- What can we learn about human evolution from the fossil record?

In-Class Activity

Click here to access Lecture ppt specifically designed for chapter 20.

Click here to access Clicker Questions specifically designed for chapter 20.

HEN BARACK OBAMA WAS ELECTED FOR HIS FIRST term in 2008, he was hailed as America’s first black president. When Tiger Woods won the Masters Golf Tournament in 1997, he was lauded as the first black man to win. When Halle Berry won an Oscar in 2001 for best actress, she was commended as the first black woman to win in that category.

HEN BARACK OBAMA WAS ELECTED FOR HIS FIRST term in 2008, he was hailed as America’s first black president. When Tiger Woods won the Masters Golf Tournament in 1997, he was lauded as the first black man to win. When Halle Berry won an Oscar in 2001 for best actress, she was commended as the first black woman to win in that category.

Why was skin color so significant? A 250-year history of slavery and racial discrimination in the United States has left a bitter legacy. Almost 150 years after slavery was legally abolished in the United States, people of color are still underrepresented in positions of power and prestige. Although the reasons for this underrepresentation are complex, the recognition of the achievements of Obama, Woods, and Berry signaled a major change: barriers to social advancement were beginning to come down.

To shoehorn any of these three people into a simple racial category, however, is misleading: Barack Obama was born to a white mother and a black African father; Tiger Woods’s background includes African, Chinese, Dutch, and Thai forebears; Halle Berry was born to a white mother and an African-American father. So what does the term “black” mean?

Historically, racial categories were employed by one group to maintain power over another and to justify forms of oppression, including slavery. In the United States, racial categories were reinforced by laws like the “one drop” rule adopted by several states in the 1920s, which held that any American with one drop of African blood was to be considered black. People then continued to use these categories and their connotations to justify racial discrimination and, in some places, racial segregation.

Though social and political attitudes have changed, people continue to invoke racial categories like “black” or “white” for various reasons, including simple physical description. From a biological perspective, however, it is increasingly clear that racial categories have little meaning. Research on human genetics shows that race is a social, not a biological, category. Groups of people can and do share similar physical characteristics, such as skin color and other features, but these superficial differences obscure how fundamentally similar human beings are.

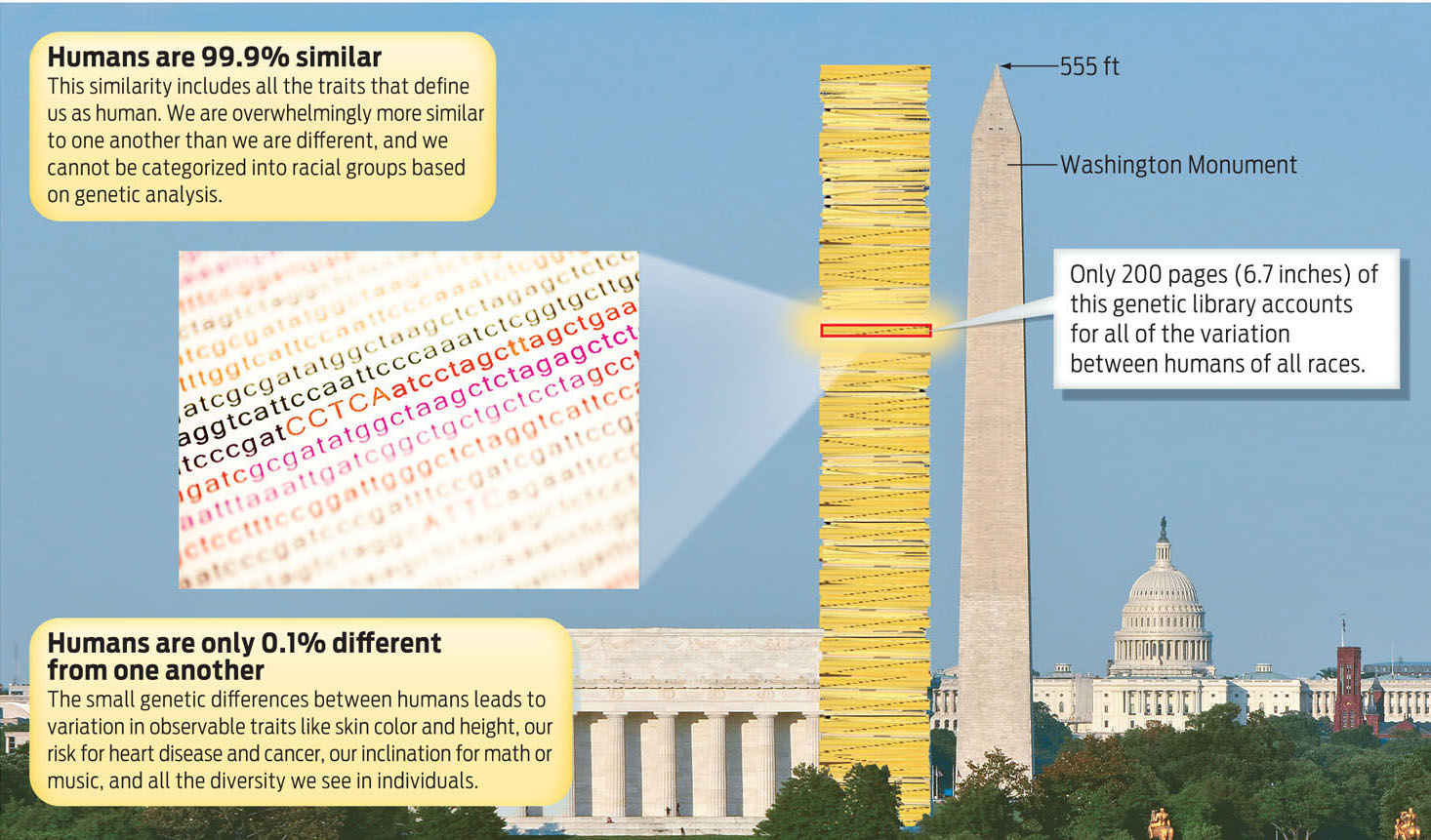

All humans are members of a single biological species, Homo sapiens. Biologically, we are far more similar to one another than we are different. In fact, genetic studies comparing regions of the human genome from person to person show that each person’s DNA is 99.9% identical to that of any other unrelated person. It is only in the remaining 0.1% of our DNA that we differ, and it is this tiny fraction that accounts for the diversity of traits we see from person to person (INFOGRAPHIC 20.1).

The human genome includes 3 billion nucleotide base pairs. Its entire sequence of A, G, T, and C nucleotide bases would fit into 200 phone books, each 1,000 pages long. When stacked, the phone books would reach to the top of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C. That’s 200,000 pages of genetic code!

If people are so fundamentally similar on a biological level, why is there so much variation in human skin tone? And how did these differences come about? The answers lie in the evolution and migration of our earliest ancestors. Humans are a recent species, first walking the Earth a mere 200,000 years ago. Since that time, humans have evolved many traits that helped them survive the environments they encountered as they migrated around the globe. People with African ancestry, for example, carry with high frequency an allele that helps them resist malaria. An allele common among Northern Europeans enables them as adults to digest milk better than other populations do, an indication that at some point in history, dairy products provided an important source of nutrition and those who could digest them were more likely than others to survive. Tibetans carry in high frequency an allele that helps their red blood cells compensate for the low oxygen level in their high-altitude environment.

Skin color is another example of human evolution. For many years, scientists had wondered why humans differ in their skin color. But it wasn’t until the work of Nina Jablonski, an anthropologist at Pennsylvania State University, that they found a convincing answer.