A SWARM OF PROBLEMS

The United States is home to approximately 1,000 commercial beekeepers, who together cultivate about 2.5 million bee colonies. To a beekeeper–essentially a small business owner–losing 30% of his or her colonies represents an unsustainable financial loss. The sudden bee disappearances of 2006 were a serious worry for Dave Hackenberg and other beekeepers.

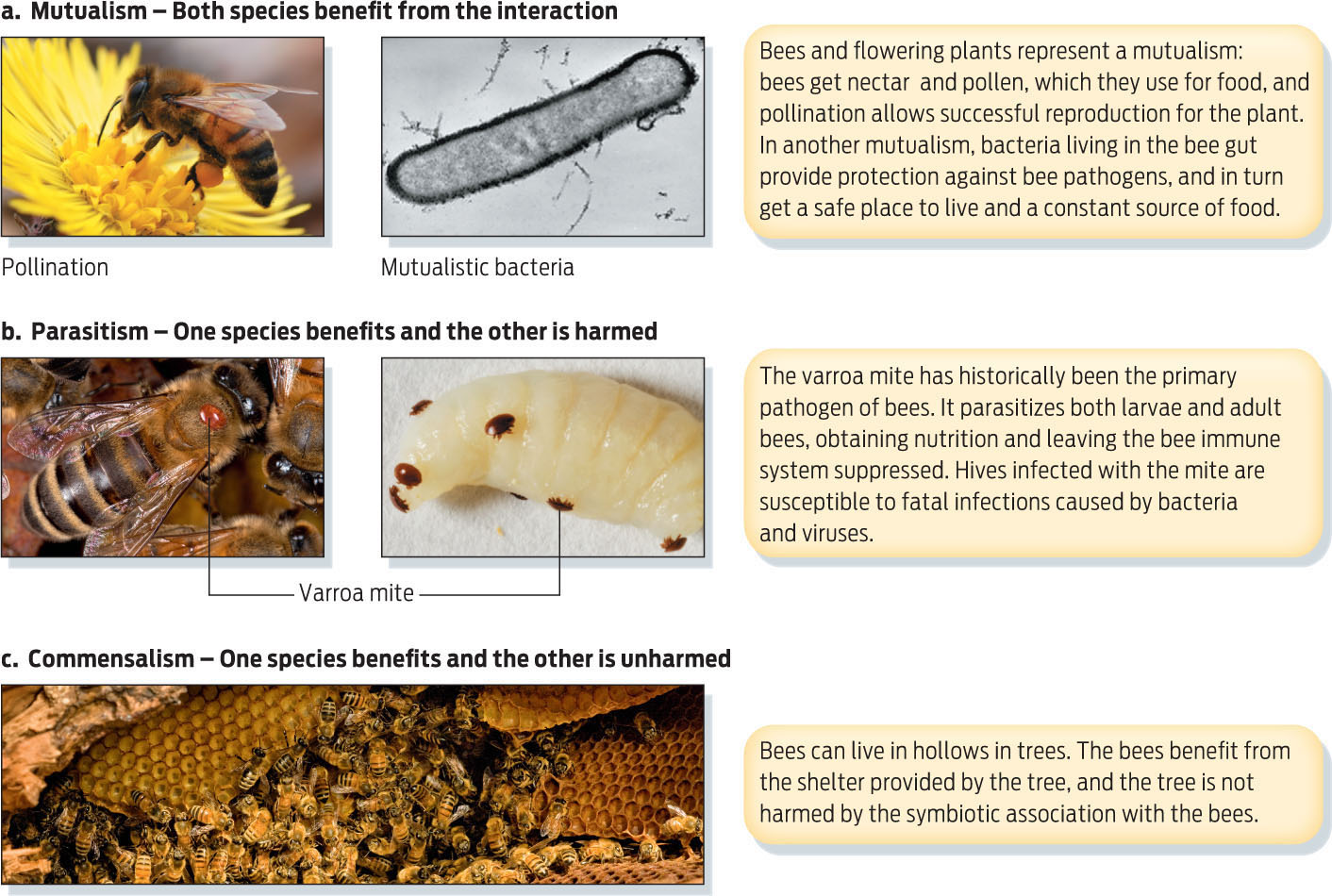

PARASITISM A type of symbiotic relationship in which one member benefits at the expense of the other.

While the losses from CCD have indeed been considerable, this was actually not the first time that beekeepers’ livelihood has been hit hard. Since 1987, beekeepers have had to battle significant annual losses from an aggressive pest: the blood-sucking varroa mite.

SYMBIOSIS A relationship in which two different organisms live together, often interdependently.

An invasive species, the varroa mite was likely introduced into the United States on the backs of imported bees. The sesame seed–size freeloader is a parasite that feeds on bees’ blood, weakening their immune systems and spreading viruses. Parasitism is a type of symbiosis–a close relationship between two species–in which one species (in this case, the mite) clearly benefits, and one species (the honey bee) clearly loses. Because it involves one species feeding on another, parasitism is also a form of predation.

MUTUALISM A type of symbiotic relationship in which both members benefit; a “win-win” relationship.

Not all symbiotic relationships are harmful to one of the partners; they can sometimes be mutually beneficial. Bees and flowering plants are a perfect example of one such mutualism. Bees can’t survive without the flowers, which provide food, and plants depend on the bees to help them reproduce. Honey bees have other mutualistic symbioses, as well, including with bacteria that live safely inside the bees and benefit their hosts by helping them combat disease.

COMMENSALISM A type of symbiotic relationship in which one member benefits and the other is unharmed.

A third type of symbiotic relationship is commensalism, a relationship in which one species benefits while the other is unaffected or unharmed–bees living in a hollowed-out oak tree, for example (INFOGRAPHIC 22.6).

Symbioses are relationships in which different species live together in close association. These associations can provide benefits, harm, or have no effect on the partners involved.

As devastating as the parasitic varroa mite infestation has been, it is unlikely to be the sole or even primary factor responsible for the most recent colony collapses. Research by apiarist vanEngelsdorp, and others has shown that levels of mite infections in collapsing colonies are no higher than they had been in previous years. Moreover, a mite infestation does not explain the most curious aspect of the condition: the sudden disappearance of entire hives.

Honey bees are a colonial species: they live in hives of thousands of individuals, in which worker bees collectively support all the juvenile larvae. In collapsing colonies, the worker bees (all female) abandon the hive. With no workers to help larvae reach maturity, the colony dies.

According to vanEngelsdorp, the worker bees may be practicing what’s called “altruistic suicide.” “The worker bee knows she’s sick,” he explains. “She knows, ‘Well, I better fly out of here and die away from the hive and maybe preserve my nest mates.’” But that altruistic practice can spiral out of control, he says, and the result is a collapsing colony.

Alternatively, the sick bees may simply have trouble finding their way back to the hive.

Not surprisingly, the sudden disappearances have fueled intense speculation among beekeepers and laypeople alike about what’s going on. Hypotheses have included everything from pesticides, viruses, and genetically modified crops to cell phone radiation, global warming, and even alien abduction. It’s a baffling who-done-it with many suspects but no smoking gun.