WARMING PLANET, DIMINISHING BIODIVERSITY

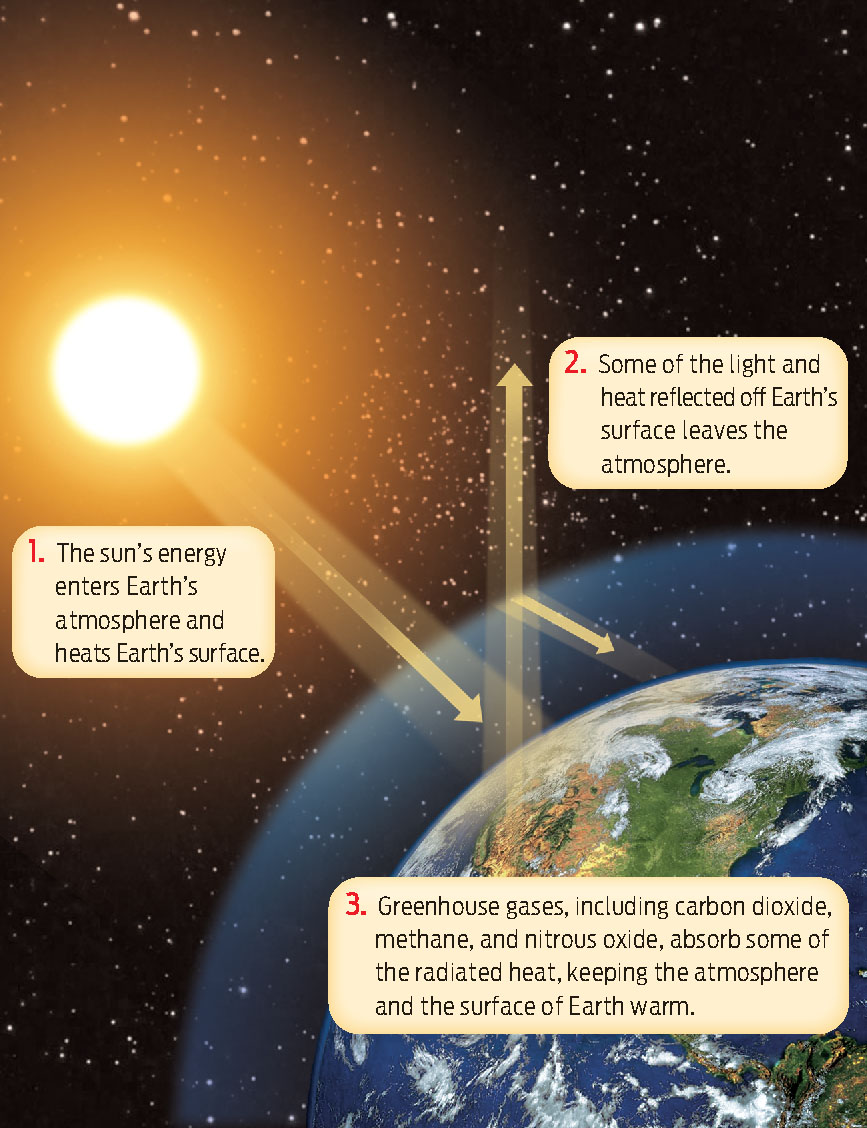

GREENHOUSE EFFECT The normal process by which heat is radiated from Earth’s surface and trapped by gases in the atmosphere, helping to maintain Earth at a temperature that can support life.

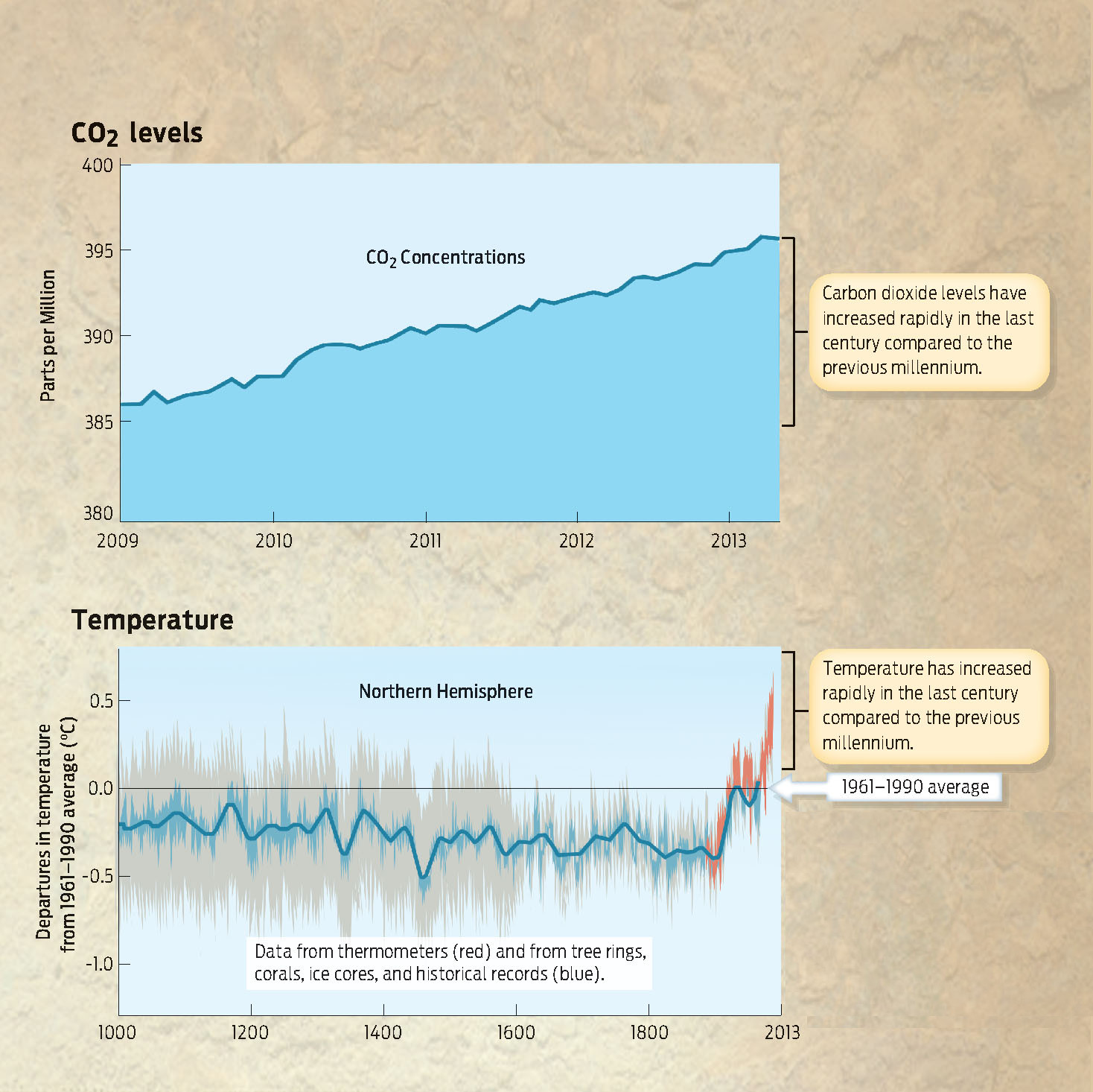

Although temperature swings and shifts in the ranges of organisms are natural phenomena, the amount of warming in recent years is unprecedented, and evidence suggests that the change is not merely part of a natural cycle. From 1880 until 2012, Earth’s surface has warmed, on average, by about 0.8°C (1.4°F), according to a 2013 report by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. That may not sound like a lot. But consider this: the difference in average global temperatures between today and the last ice age—10,000 years ago, when much of North America was buried under ice—is only about 5°C (9° F). Where global temperatures are concerned, even a 1° change is significant.

GREENHOUSE GAS Any of the gases in Earth’s atmosphere that absorb heat radiated from Earth’s surface and contribute to the greenhouse effect; for example, carbon dioxide and methane.

The rate of warming has increased as well. Ten of the warmest years on record have occurred since 1998. The last decade, from 2000 through 2010, was the hottest decade so far, with 2010 tying 2005 for the title of hottest year on record. For the continental United States, 2012 broke the heat record. Much of this warming is attributable to the greenhouse effect, the trapping of heat in Earth’s atmosphere. As sunlight shines on our planet, it warms Earth’s surface. This heat radiates back to the atmosphere, where it is absorbed by greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide. The heat trapped by greenhouse gases raises the temperature of the atmosphere, and in turn, Earth’s surface (INFOGRAPHIC 23.4).

The greenhouse effect is a natural process that helps maintain steady and life-sustaining surface temperatures on Earth. Sunlight heats Earth’s surface and that heat radiates back to the atmosphere. While some of the heat escapes to space, certain gases in Earth’s atmosphere, known as greenhouse gases, trap heat within the atmosphere. This trapped heat warms the atmosphere and Earth’s surface.

The greenhouse effect is a natural process that helps maintain life-supporting temperatures on Earth. Without this greenhouse effect, the average surface temperature of the planet would be a frigid −18°C (0°F). In recent years, however, rising levels of greenhouse gases have increased the strength of the greenhouse effect, a phenomenon known as the enhanced greenhouse effect. As the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has increased, so have temperatures. The result is global warming, an overall increase in Earth’s average temperature (INFOGRAPHIC 23.5).

As measured directly by thermometers and as documented by historical records and other biological indicators (including tree rings, corals, and ice cores) the temperature on Earth has increased rapidly in the past 140 years. This is paralleled by an increase in greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide.

For ecologist Hector Galbraith, director of the Climate Change Initiative at the Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences, in Plymouth, Massachusetts, the most worrying thing about climate change is how quickly it is happening and how sensitive species are to the changes. “Most people think of climate change as something that’s 30 years out,” says Galbraith. But that’s simply not true, he notes. “We began seeing responses in ecosystems 20 years ago. The ecosystems knew about it before we did.”

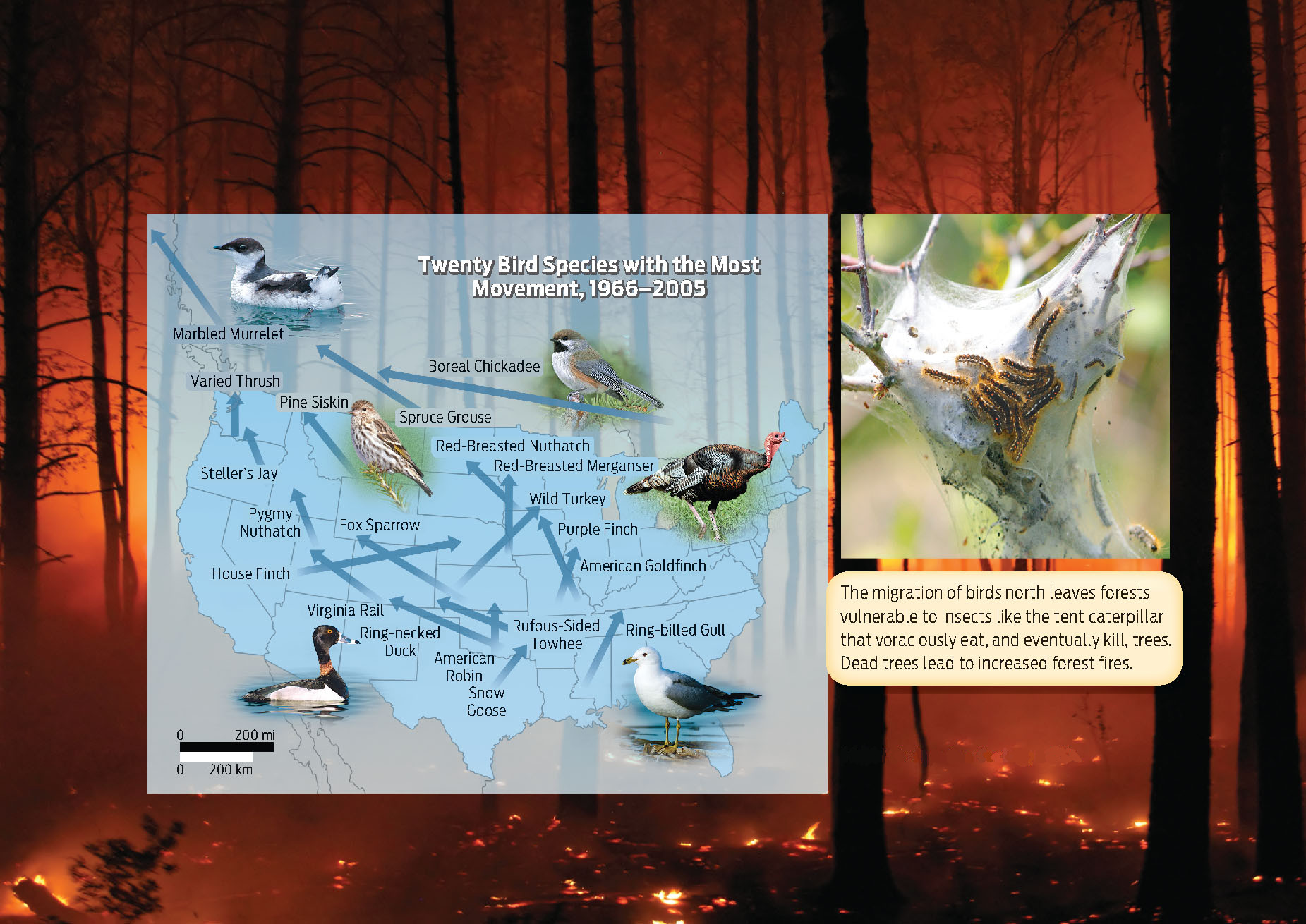

Plants, of course, are slower to adapt than animals; they cannot simply get up and move (although they may change their range over time by dispersing seeds into more favorable habitats). But some animals can change their ranges quite quickly. “A bird can simply open its wings, and within 2 hours it’s 50 miles farther north,” says Galbraith.

What will be the outcome of all these changes? We don’t really know. “We’re seeing changes to systems that have been relatively stable for thousands of years,” says Galbraith. “The really scary thing about climate change is it’s very difficult to predict the ecosystem effects of these changes.”

Nevertheless, there are disturbing scenarios. Take the relationship between birds and insects. Many forests are susceptible to insect attacks. Given their insect-rich diet, birds are a natural form of pest control in these forests. If the birds move north, as evidence suggests they are doing, the forests they leave behind will be more vulnerable to threats from insects that thrive in warmer, drier weather. The maple-tree-loving pear thrip and the forest tent caterpillar are just two examples of insects that might be happy to see the birds go. More insects means more dead trees, which in turn means more fuel for forest fires (INFOGRAPHIC 23.6).

Climate change is having dramatic impacts on entire ecosystems. The Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count has shown that 58% of 305 bird species studied have shifted their winter ranges significantly northward, and that this shift correlates with increasing temperature. This has implications for insect control, leaving forests vulnerable to fire when insects are not eaten by birds.

Not all species will be negatively affected by climate change—some may actually benefit. But one species’ success in coping with climate change may contribute to another’s demise. For example, the adaptable red fox (Vulpes vulpes), found throughout the northern hemisphere, is venturing into the range of the endangered Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), whose habitat—the Arctic tundra—has become warmer. When the two species share a range, the Arctic fox inevitably suffers because the red fox out-competes it for food and also preys on Arctic fox pups.

While some species can adapt to a changing climate by shifting range, future climate change will likely exceed the ability of many species to adapt, as hospitable habitats can no longer be found or accessed. According to a 2011 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1 in 10 species could be driven to extinction by 2100 because of climate change. The natural residents of mountaintops are especially vulnerable: as temperatures rise, species may move up to higher, colder elevations, but eventually they will have nowhere left to go.