ARCTIC MELTDOWN

Predictably, snow- and ice-covered regions such as the Arctic stand to suffer most immediately from a warming climate, as frozen habitats start to melt. But the situation is worse than one might imagine. As Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado, Boulder, notes, the Arctic has warmed, on average, twice as much as the rest of the planet. This phenomenon is known among climate scientists as Arctic amplification, and it has to do with the way sea ice affects temperature. As Serreze explains, sea ice both reflects solar radiation and insulates the ocean. As global temperatures rise, ice begins to melt. With less sea ice, more solar radiation is absorbed by the ocean and more of the relatively warm ocean is exposed to air, raising the air temperature even more. It’s a positive feedback loop: as additional ice is lost, temperatures rise at an accelerated pace.

According to the extensive Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, the result of 4 years’ work by more than 300 scientists around the world, Arctic temperatures are projected to rise by an additional 4°−7°C (7°–13°F) over the next 100 years (INFOGRAPHIC 23.7).

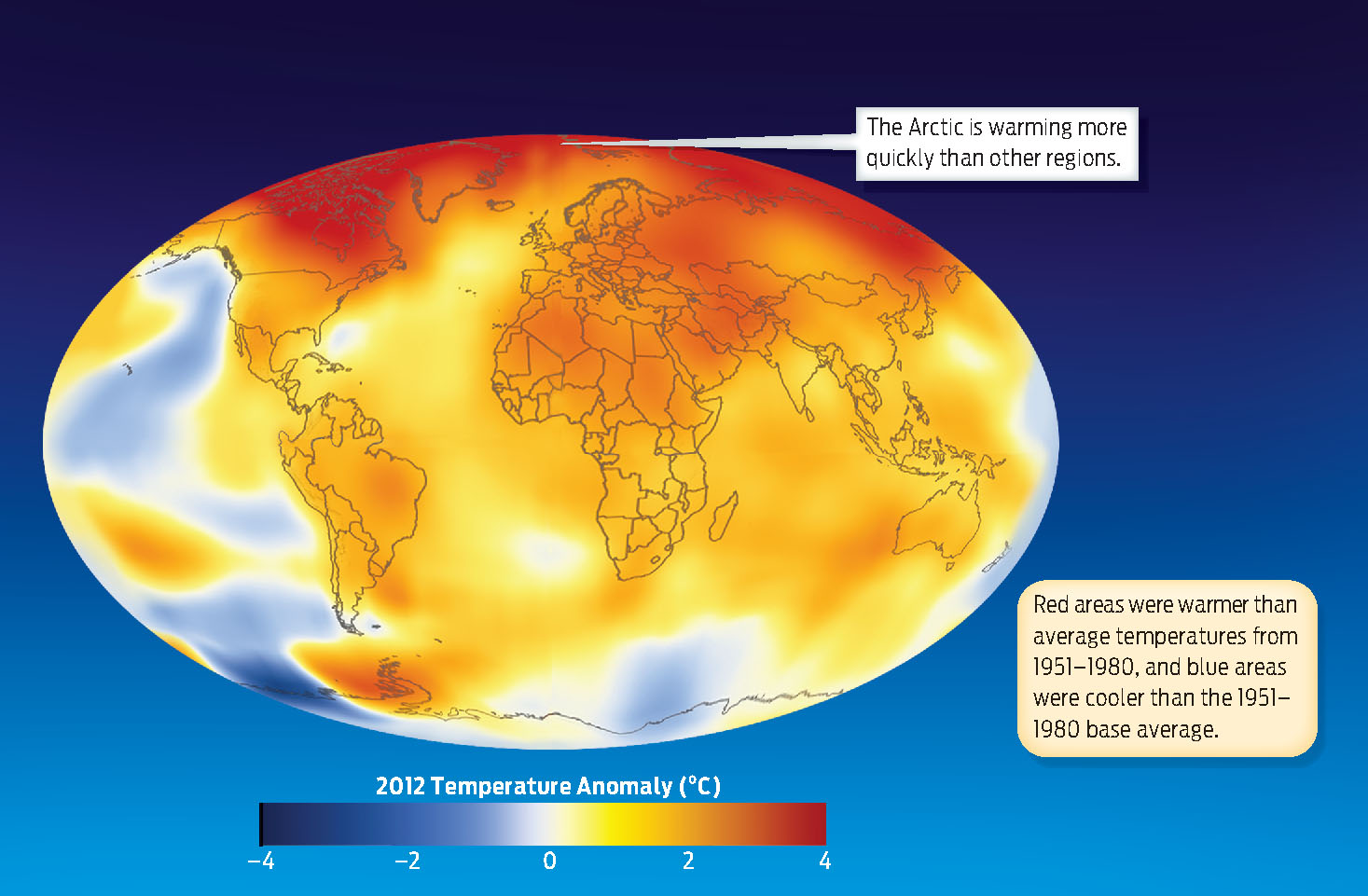

Current measurements suggest that the Arctic is warming faster than other parts of Earth. The year 2012 was the ninth warmest year on record (since measurements began in 1880). Much of Earth was warmer in 2012 than average temperatures from 1951 to 1980. The Arctic was notably warmer in 2012.

Warming temperatures could spell disaster for species that call the Arctic their home. Polar bears, for example, spend most of the year roaming the Arctic on large swaths of floating sea ice that blanket a good portion of the Arctic Ocean from September through March. The massive mammals travel on sea ice to hunt for seals, which periodically pop up through “whack-a-mole”–like breathing holes in the ice and are nabbed by the bears. The size of this frozen habitat has been shrinking, greatly reducing the bears’ ability to obtain food.

Moreover, over the past few decades the ice has been breaking up earlier and earlier in spring. The sea ice in Hudson Bay, Canada, for example, now breaks up nearly 3 weeks earlier than it did in the 1970s. In the absence of sufficient summer sea ice, the polar bears are stuck on land (where there are no seals), or are forced to swim long distances to reach sea ice. Some, exhausted by the journey, drown. Those that do survive have fewer opportunities to hunt. Canadian polar bears now weigh on average 55 pounds less than they did 30 years ago, a loss that seriously compromises their reproductive ability.

Scientists have monitored sea ice daily by satellite since 1979. Over the past three decades, the area of Arctic sea ice has shrunk by more than 1 million square miles, an area roughly four times the size of Texas, according to Walt Meier, a research scientist with the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Arctic sea ice hit a record low in September 2012, at the end of the summer melt season, shrinking to a level that climate change models had predicted wouldn’t happen until at least 2050. Scientists now fear that nearly all of the polar bear’s summer sea ice could vanish by 2040—possibly sooner (INFOGRAPHIC 23.8).

Rising temperatures have caused the Arctic sea ice to melt and break apart earlier in the season. The reduction in the extent of summer sea ice is threatening the survival of polar bears, which require the sea ice to hunt for seals.

Warming temperatures are also causing glaciers and ice caps on land to melt. Unlike sea ice, which, like an ice cube in a glass of water, doesn’t raise the water level as it melts, melting glaciers and ice caps do. How much will seas rise? “By 2100, you’re looking at probably about a meter,” says Serreze. “Here in Boulder we’re at 5,400 feet—we’re not worried about that. But if you’re living in Miami, this is something that should concern you.”

It’s important to note that much of the data we have on climate change relates to global, long-term trends. From year to year, there may be slight variations—slightly warmer summers and less sea ice one year, slightly cooler summers and more sea ice the next. And indeed, from a low in 2007, sea ice did indeed bounce back a bit in 2008 and 2009. But the overall trend is still unmistakably downward—toward less sea ice. By 2030 or 2040, says Serreze, there could be no summer ice to speak of. “You could take a ship across the north pole.”