IT AIN’T EASY BEING GREEN

Billman says she and her colleagues were largely successful in realizing a green agenda in Greensburg because they had significant buy-in from the town. But going green is not always easy for cities to do, and there are many factors to consider besides environmental impact.

One is your audience. You have to know where people are coming from and use language that speaks to their core values, says Billman. If leaders had tried to push a green agenda on citizens by stressing only environmental benefits, it would likely have fallen flat. Indeed, while environmental concerns were important to city leaders, they carried less weight with many ordinary citizens. “It was negative for us to bring up climate change,” says Billman. “So we didn’t.”

Instead, she says, they stressed the two angles that resonated most with this community: cost savings and resiliency—building things to last. Ultimately, the same goal was achieved: a town that saw the value of renewable energy.

From an ecological standpoint, the appeal of renewable sources of energy such as wind and solar is undeniable: they are plentiful, powerful, and environmentally neutral in their carbon emissions. Solar power alone could theoretically provide more than enough clean energy to supply the needs of everyone on the planet many times over-assuming we could adequately and inexpensively harvest it.

The major problem with wind and solar power is that the technologies to harness them are currently much more expensive to build and operate than ones based on oil, coal, and natural gas. What makes fossil fuels such convenient and inexpensive sources of energy is the fact that the difficult work of harvesting the energy of sunlight has already been done by the photosynthetic organisms that were compressed over millions of years into oil, coal, and gas. (In a way, we are already using the energy of sunlight to power our lifestyles, but indirectly.) New natural gas and oil harvesting technologies, like hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”), have upped the ante even more since they deliver products that are cheaper than coal.

Of course, when you consider the environmental and human costs of obtaining and burning fossil fuels—from coal-mine explosions to air and water pollution to oil spills—they aren’t actually that cheap. Think of the 2010 disaster in the Gulf of Mexico: an oil rig exploded and sank, spewing 4.9 million barrels of oil into the Gulf and costing 11 lives and more than $40 billion in cleanup. Or consider that hydraulic fracturing can lead to serious water pollution, including contaminated drinking wells that pump out flammable water. These downstream costs of fossil fuels, which are not reflected in their market price, are known among economists as externalities. If externalities were included in the price, as some economists and environmentalists suggest they should be, then the playing field with other forms of energy would be more level.

Moreover, explains Billman, the government subsidizes fossil fuel use in lots of ways that aren’t as obvious to the public. According to a 2009 study by the nonpartisan Environmental Law Institute, the U.S. government provided $72 billion in tax breaks and subsidies to the fossil fuel industry over the years 2002–2008 versus $29 billion to renewable energy companies over the same period. Such hidden subsidies can create disincentives to change.

But as Greensburg shows, there are ways to make renewables more competitive. First and foremost, there’s the approach of emphasizing cost savings: when energy savings over time are considered in the math, the economic calculations look pretty good. As Mike Estes, owner of the local John Deere dealership, experienced firsthand, renewables make up for their initial higher price by saving money in the long term.

There are also ways to capitalize on the desire of companies that want to become better stewards of the environment. The Greensburg wind farm, for example, was funded in part with money provided by Vermont-based NativeEnergy, a company that sells “carbon offsets” to businesses that want to counterbalance their fossil fuel use (but may not be able to implement substantial carbon reductions of their own). Current purchasers of NativeEnergy carbon offsets include Ben & Jerry’s, Stonyfield Farm, Clif Bar, and Green Mountain Coffee Roasters.

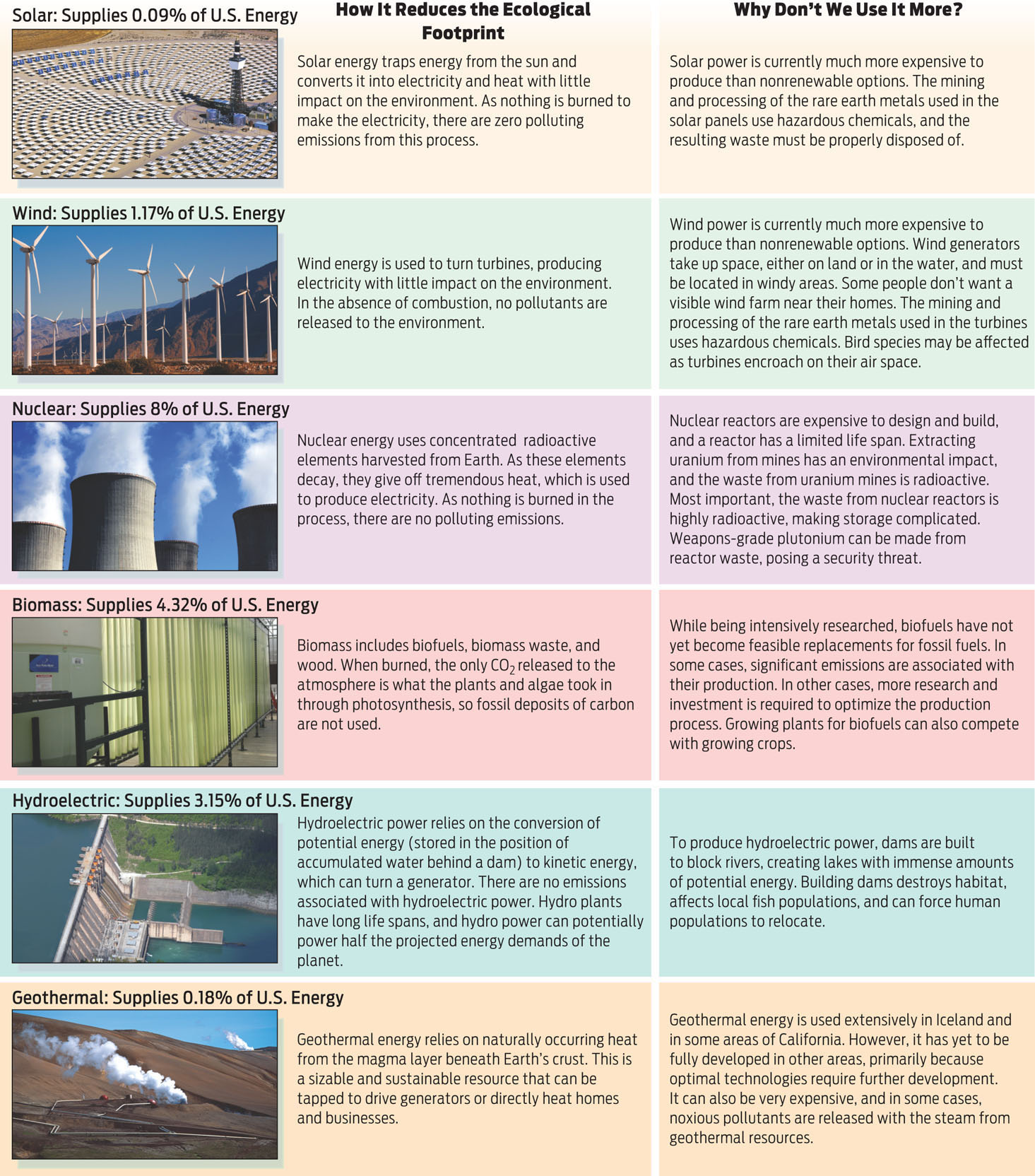

Yet there are factors besides cost that limit how much we can rely on renewables at present. The most significant are technological problems of storing and transmitting energy produced from wind and solar. Threats posed by wind farms and solar panels to native animal habitat also complicate the picture. Given these limitations, says Billman, “wind and solar still are a ways from sweeping over the country.” The same goes for algae-based biofuels (see Chapter 5) and other renewables. At least for the next decade, we cannot take fossil fuels out of our energy mix (INFOGRAPHIC 24.7).

While many renewable resources are available to us, economic, technological, and environmental considerations currently limit their use as alternatives to fossil fuels.