Chapter Introduction

DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- How are the bodies of living organisms organized?

- How do humans and other organisms regulate body temperature?

- What physiological systems are regulated by homeostatic feedback loops?

In-Class Activity

Click here to access Lecture ppt specifically designed for chapter 25.

Click here to access Clicker Questions specifically designed for chapter 25.

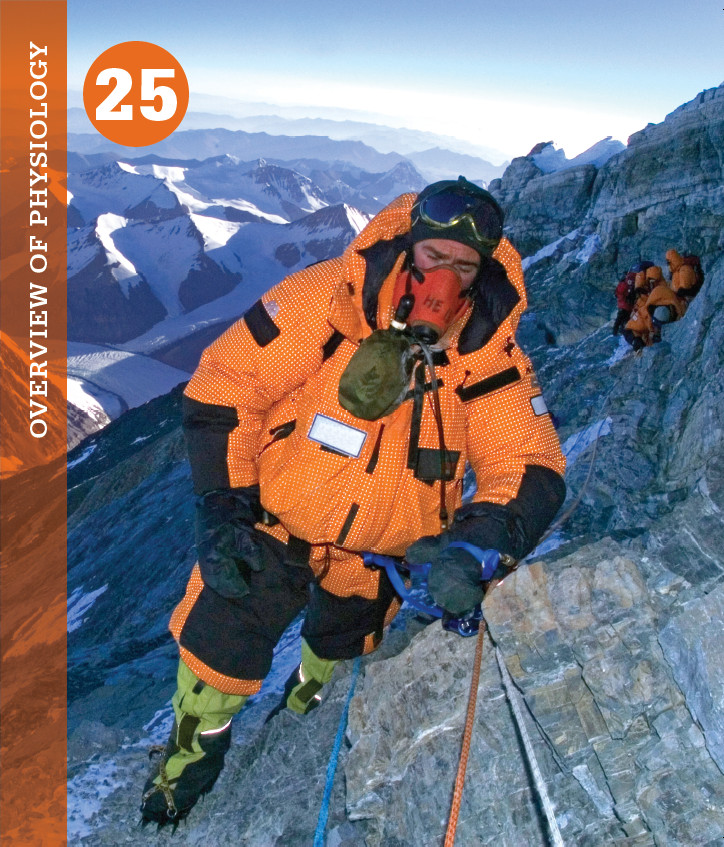

T 1:17 P.M., ON MAY 10, 1996, JON KRAKAUER PLANTED ONE FOOT IN CHINA, the other in Nepal, and stood on the roof of the world. He was at the highest point above sea level that any human has ever reached—short of standing on the moon. Yet he didn’t feel like celebrating. It had taken him 6 long weeks to climb to the top of Mount Everest, and now that he was here his toes ached in the subzero cold, his breath came in short, painful bursts, and his head pounded from the altitude. It was a struggle just to stay upright. “I cleared the ice from my oxygen mask, hunched a shoulder against the wind, and stared absently at the vast sweep of earth below,” wrote Krakauer in an account of his climb for Outside magazine later that year.

T 1:17 P.M., ON MAY 10, 1996, JON KRAKAUER PLANTED ONE FOOT IN CHINA, the other in Nepal, and stood on the roof of the world. He was at the highest point above sea level that any human has ever reached—short of standing on the moon. Yet he didn’t feel like celebrating. It had taken him 6 long weeks to climb to the top of Mount Everest, and now that he was here his toes ached in the subzero cold, his breath came in short, painful bursts, and his head pounded from the altitude. It was a struggle just to stay upright. “I cleared the ice from my oxygen mask, hunched a shoulder against the wind, and stared absently at the vast sweep of earth below,” wrote Krakauer in an account of his climb for Outside magazine later that year.

Krakauer’s journey to Everest was a lifetime in the making. While other kids were idolizing astronaut John Glenn and baseball pitcher Sandy Koufax, Krakauer’s childhood heroes were Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld—two men from his hometown in Oregon who, in 1963, became the first climbers to scale the daunting western ridge of Everest. As a teenager, Krakauer became a skilled climber, vanquishing many of the world’s most difficult peaks, and he dreamed of one day climbing Everest himself. By his mid-twenties, though, he had largely abandoned the idea as a boyhood fantasy. But old dreams die hard.

In 1995, Krakauer was working as a journalist when the opportunity came to shadow an Everest climb and report on it for Outside magazine. The 42-year-old writer-adventurer jumped at the chance. He would join a team headed by the celebrated climbing guide Rob Hall, whose company, Adventure Consultants, had successfully put 39 amateur climbers on top of Everest. Reaching the summit himself would mean enduring a weeks-long ascent from Base Camp, giving his body time to adjust to the high altitude.

It would also mean risking his life on a daily basis.

The icy tip of Mount Everest sits at 29,035 feet above sea level; cruising altitude of most commercial jetliners is 30,000 feet. A human plucked from sea level and deposited at this altitude would quickly lose consciousness and die. A climber who has spent weeks adjusting to the altitude can function better at the summit, but not very well, and not for very long. Everest is not only the highest place on Earth, it is also one of the coldest. At the summit, where windchill temperatures average −53°C (−63°F), freezing to death is a real possibility.

Despite these dangers—or perhaps because of them—about 150 fearless men and women try to climb Everest every season. And every season, some of them don’t come back. Ten people died on Everest in 2012. In the first half of 2013 alone, nine climbers perished. There are many reasons for these disasters—poor training, unforeseen accidents, raw egotism—but among the most important is basic biology: the human body is not equipped to survive at such extreme altitude, and such extreme temperature, for long.

At the summit, where windchill temperatures average −53°C (−63°F), freezing to death is a real possibility.