INTO THIN AIR

HYPOXIA A state of low oxygen concentration in the blood.

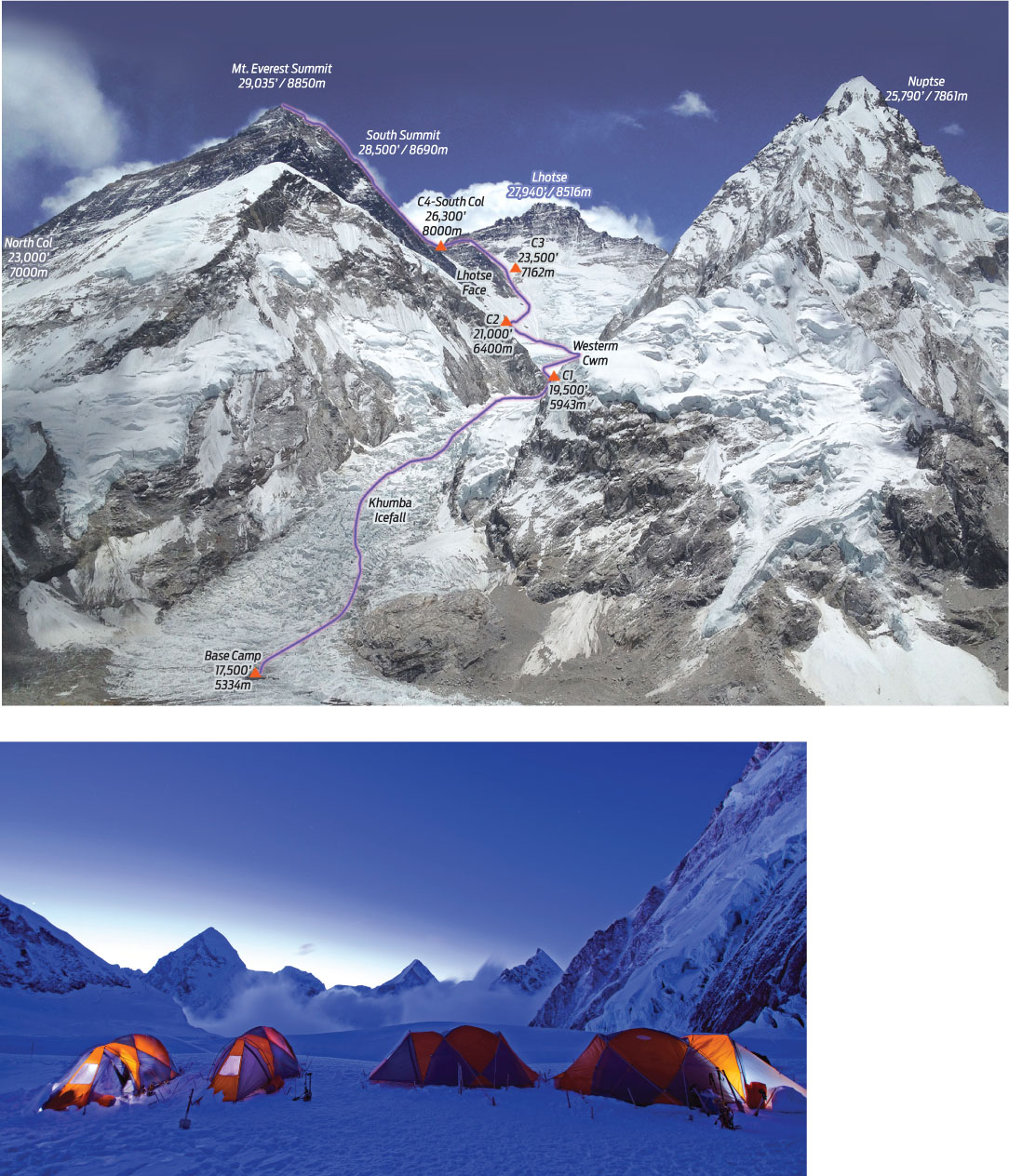

The 15-member team left camp shortly after 11 P.M. Night climbing is necessary on Everest in order to arrive at the most difficult parts of the climb during daylight hours and still have enough time to get back down to camp before nightfall. Krakauer led the pack that night, along with the team’s head Sherpa, Ang Dorjee.

The pair reached the Southeast Ridge, the second to last stop before the summit, at 5:30 A.M., just as the sun was peering over the eastern peaks. By this time, Krakauer’s hands and feet felt like unwieldy blocks of ice, nearly useless in performing the delicate work of laying ropes and scaling ice. But it wasn’t just the cold he had to deal with. His brain and body were also showing the effects of altitude: “Plodding slowly up the last few steps to the summit,” wrote Krakauer in Into Thin Air, his 1997 book about the expedition, “I had the sensation of being underwater, of life moving at quarter speed.”

At high altitudes, there is lower barometric pressure, which means there are fewer air molecules banging around in the atmosphere—including fewer molecules of oxygen. The percentage of oxygen in the air is the same as at sea level (about 20%), but since there are many fewer air molecules overall, the pressure of oxygen is much less, and therefore fewer oxygen molecules are taken in per breath of air (see Chapter 28). The lower pressure means that fewer oxygen molecules bind to the hemoglobin in blood, which means that blood is less saturated with oxygen, a condition called hypoxia. Since all cells require oxygen to function, hypoxia has many bodily consequences. The most serious and immediate occur in the brain. “I’ve been at 19- and 20,000 feet climbing myself,” says physiologist Kenefick, “and I can tell you that doing simple tasks like tying your shoes—even though you’ve tied your shoes many times—is much more difficult.” For the hikers on Everest, he says, each step would have been a struggle.

ACCLIMATIZATION The process of physiologically adjusting to an environmental change over a period of time. Acclimatization is generally reversible.

To help cope with conditions of low oxygen, climbers spend about 6 weeks acclimatizing their bodies to the conditions, spending a few nights at progressively higher elevations. Their bodies respond by increasing the production of red blood cells, the cells that contain hemoglobin and carry oxygen. The physiological adjustment of acclimatization allows a climber to carry more oxygen than could someone coming straight from sea level. But even well-acclimatized climbers usually need bottled oxygen to reach the summit successfully.

At 1:17 P.M., after more than 12 hours of climbing, Krakauer finally reached the summit. It was smaller than he expected—a patch of ice the size of a picnic table, with Buddhist prayer flags tied to a pole and flapping noisily in the wind. He stood and took in the 360° view. The towering peaks of the surrounding Himalayas, which had once loomed so large, now sat below him, draped in low-lying clouds. Beyond the mountain range, endless miles of continent stretched to the horizon.

Standing on top of the world, Krakauer was surprised by his lack of elation. He had just cleared a huge personal hurdle, yet the victory felt hollow. Partly, he was too exhausted to truly care: he hadn’t slept soundly in more than 50 hours, and the only food he had been able to choke down in 3 days was a bowl of ramen soup and some peanut M&Ms (sleep disturbances and digestive difficulties are additional side effects of high elevation). But another thought lurked in his brain: the oxygen tank he had slung on his back to help him breathe was running low, and he still had to get down the mountain.

“With enough determination, any bloody idiot can get up this hill,” guide Rob Hall had famously said. “The trick is to get back down alive.” Keenly aware of the clock, Krakauer snapped a few perfunctory photos, and within 5 minutes was headed back down the mountain toward Camp IV on the Col.

Fifteen minutes later, after scaling the steep ice fin of the Southeast Ridge, he arrived at the pronounced notch in the mountain known as the South Summit, just below the main peak. As he prepared to rappel over the edge, he caught a glimpse of an alarming sight: a queue of 20 climbers, from three separate expeditions, waiting to come up. They were backed up at the notorious Hillary Step—a 40-foot wall of rock and ice named for Sir Edmund Hillary, who, with Tenzing Norgay, was the first to scale it successfully, in 1954. Getting up the Step requires ropes, so climbers must go up one by one, and on this day there was a traffic jam.

While waiting for his turn to get down the Step, Krakauer peered into the distance and saw something he hadn’t noticed before: on the horizon, dark clouds were sweeping in from the south, filling up a corner of what had been a clear blue sky. A storm was brewing.

By this point, it was well past the agreed-upon turnaround time of 1 P.M. set by Hall. The climbers who were still headed up the mountain at this hour were willfully flouting safety rules. Not only that, weather conditions were getting worse. Snow had started to fall, and it had become hard to see where mountain ended and sky began. The lower Krakauer got on the mountain, the worse the weather became.

Krakauer made it back to Camp IV on the Col just before 6 P.M. The bedraggled climber fell into his tent and quickly passed out. He was delirious, shivering uncontrollably, and exhausted. But he was alive.