WARNING SIGNS

Hypothermia isn’t only a danger for death-defying mountain climbers: it’s a leading cause of death during outdoor recreation like rafting and skiing, and is the number one way to lose your life while outdoors in cold weather. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that hypothermia causes more than 1,000 deaths each year in the United States.

Wilderness medicine experts say the best way to prevent hypothermia—in addition to dressing appropriately and carrying plenty of food and water—is to be aware of its signs. In particular, watch for the “umbles”: stumbles, mumbles, fumbles, and grumbles, which show changes in motor coordination and altered brain function. If you experience any of these signs in cold conditions, it’s time to seek shelter.

FOR COMPARISON How Do Other Organisms Thermoregulate?

| FOR COMPARISON | How Do Other Organisms Thermoregulate? |

In the face of extreme cold, humans strive to maintain a constant body temperature. Although we may pile on warm clothes or sit by a fire, most of our heat is coming from metabolic reactions occurring inside our bodies. Because we use internal metabolic heat to thermoregulate, humans are classified as endotherms (“endo” meaning “inside”). We expend a great deal of energy maintaining a warm body temperature in a cold environment.

ECTOTHERM An animal that relies on environmental sources of heat, such as sunlight, to maintain its body temperature.

Like us, whales are mammals and endotherms. As you can imagine, whales face a great challenge in maintaining a sufficiently warm body temperature in the cold ocean depths. They are protected from this cold by a thick layer of fat tissue called blubber. Not only is blubber an excellent insulator that helps prevent heat loss to the environment, it does not have many surface blood vessels—an adaptation that prevents heat loss from blood to the environment. Many endothermic animals rely on feathers, fur, or fat as insulation.

In contrast to endotherms, other animals must obtain their body heat from the environment and are therefore known as ectotherms (“ecto” meaning “outside”). While these animals are commonly referred to as “cold-blooded,” their body temperature actually mimics that of their environment. By using behavioral adaptations, many ectotherms also maintain a relatively stable body temperature (although by definition not as stable as that of endotherms’). For example, lizards bask in the sun to warm up and seek out shade or a protected burrow to prevent overheating. Through these behaviors, lizards keep their bodies in a temperature range compatible with their metabolism.

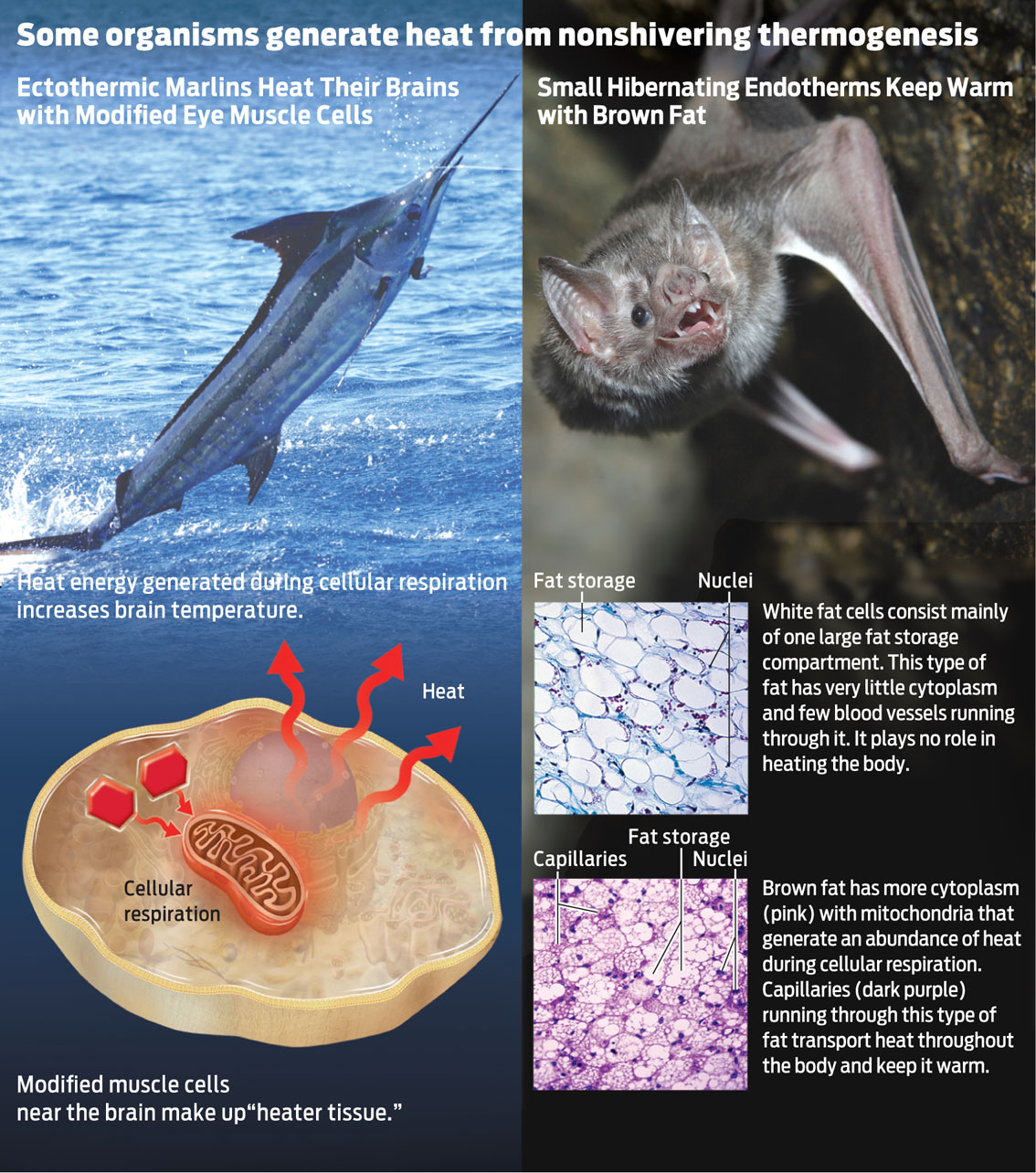

While basking in the sun works well for terrestrial ectotherms, this is not an option for certain fish, such as marlins. The surrounding water absorbs most of the heat of the sun, so marlins cannot heat themselves by swimming in sunny waters. Their brains would be dangerously close to freezing if not for specialized “heater tissue” that generates heat to keep their brains warm. In this case, the heater tissue is modified eye muscle that acts to generate heat rather than force or movement. This form of heating is a type of “non-shivering thermogenesis.”

Another form of nonshivering thermogenesis, used by bats (and human babies), occurs in a tissue known as brown fat. Brown fat is located in the neck and shoulders areas and is several degrees Celsius warmer than the rest of the body. In brown fat, specialized mitochondria convert energy to heat rather than to ATP, and the many blood vessels in brown fat deliver that heat to other parts of the body.

None of the climbers who died on Everest in 1996 was an inexperienced climber—three of them, in fact, were professional guides. Why didn’t they heed these physiological warning signs? Part of the reason is that there was simply no time. The swift-moving storm made the decision for them. But the climbers had also made questionable choices earlier that affected their fate. Whether from over-confidence or brain-addled thinking, they continued climbing toward the summit even when the hour was late. In the end, the climbers made a fatal wager with biology: in their race to the summit, they pushed themselves beyond the breaking point, overestimating, in Krakauer’s words, “the thinness of the margin by which human life is sustained above 25,000 feet.”

Not long after the disaster, Krakauer returned to climbing mountains. In a 1997 interview with Bold Type magazine, he was asked whether he was fearful of climbing again after the trauma he experienced on Everest. The chastened climber replied: “It wasn’t like ‘Am I afraid of this?’ It was more like ‘Is this right? Is it too selfish?’ I won’t go back to Everest—I’m afraid of that.”