FOOD FIX

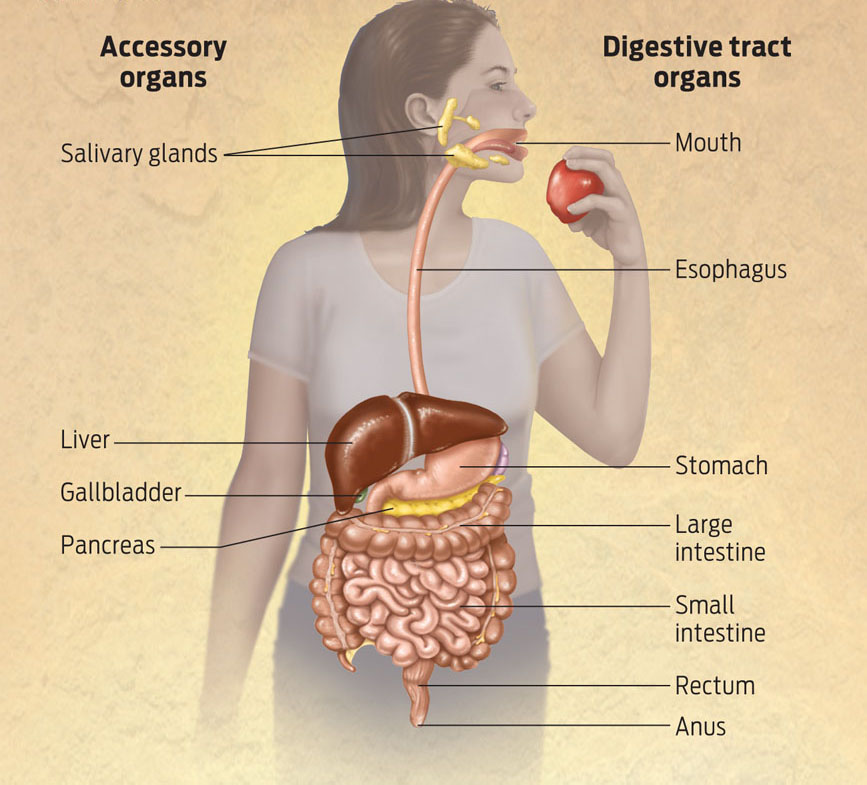

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM The organ system that breaks down food molecules into smaller subunits, absorbs nutrients, and eliminates waste; it is composed of the digestive tract and accessory organs.

The rationale behind bariatric surgery is simple: by reducing the amount of food the stomach can hold, the surgeries prevent a person from overeating. Reducing the amount of food a person takes in means less food is digested, fewer Calories are absorbed into the body, and the patient eventually loses weight.

DIGESTIVE TRACT The central pathway of the digestive system; it is a long muscular tube that pushes food between the mouth and the anus.

The stomach is an easy target for a surgical fix to overeating because it’s relatively simple to reduce its size surgically. The two most common types of bariatric surgery are gastric bypass and adjustable gastric banding (“gastric” means “of the stomach”). In gastric bypass, the stomach is surgically made smaller using staples. In adjustable gastric banding, a surgeon wraps an adjustable band around the stomach to make it smaller so that it holds less food.

The stomach is a key part of the digestive system, which breaks down food molecules into smaller subunits, absorbs nutrients, and eliminates waste. The digestive system is composed of a central digestive tract—essentially a long tube lined with muscles that extends from the mouth to the anus—as well as accessory organs that assist in digestion. As the muscles of the digestive tract alternately relax and contract, food is pushed along; accessory organs located along the length of the tract secrete enzymes and other chemicals into the tract to help break down food molecules. Through these coordinated actions, the digestive system transforms the food we eat into a form our bodies can use and rids the body of the waste left over once usable nutrients are removed from food we have taken in (INFOGRAPHIC 26.1).

The digestive system consists of a long tube with specialized sections and accessory organs that secrete enzymes and other chemicals into the digestive tract. As food travels down the digestive tract, macromolecules are broken into subunits, nutrients are absorbed, and waste is eliminated.

DIGESTION The mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into subunits, enabling the absorption of nutrients.

INGESTION The act of taking food into the mouth.

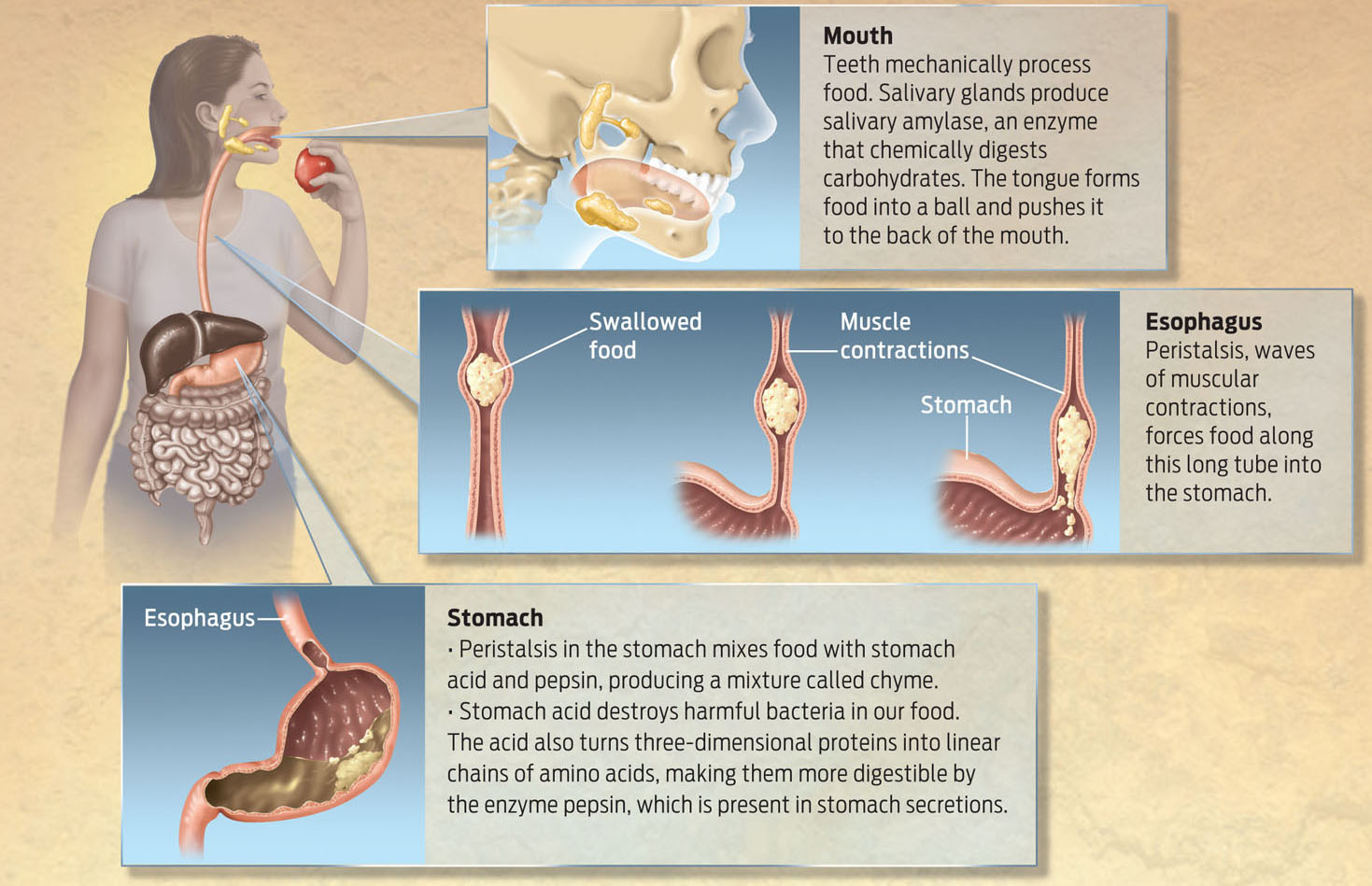

SALIVARY GLANDS Glands that secrete enzymes, including salivary amylase, which digests carbohydrates, into the mouth.

Digestion, the process of breaking down food molecules so they can be absorbed by the body, begins as soon as we put food into our mouths—ingest it. The act of chewing mechanically breaks food down into smaller pieces, while salivary glands in our mouth secrete enzymes into saliva that chemically dismantle macromolecules into their subunits. Salivary amylase, for example, breaks down carbohydrates into simpler sugars. The tongue compresses the food into a ball and works it to the back of the mouth.

ESOPHAGUS The section of the digestive tract between the mouth and the stomach.

PERISTALSIS Coordinated muscular contractions that force food down the digestive tract.

STOMACH An expandable muscular organ that stores, mechanically breaks down, and digests proteins in food.

When we swallow, food is propelled along the esophagus, the section of the digestive tract between the mouth and the stomach, by rhythmic waves of contracting muscles in a process called peristalsis. Food then enters the stomach, where stomach acid—which has a pH of close to 1, approximately the same as battery acid—destroys harmful bacteria and protects us against food-borne diseases. Stomach acid also causes proteins in food to lose their three-dimensional shapes, turning them into linear chains of amino acids. This makes it easier for the enzyme pepsin, which is produced in the stomach, to chemically break proteins apart into individual amino acids.

PEPSIN A protein-digesting enzyme that is active in the stomach.

CHYME The acidic “soup” of partially digested food that leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine.

Like the esophagus, the stomach is muscular, expanding and contracting as it accepts food and churns it. Each time it contracts, stomach acid mixes with food, producing a soupy mixture called chyme (INFOGRAPHIC 26.2).

The upper digestive tract includes the mouth, esophagus, and stomach, as well as enzymes and other chemicals secreted by the salivary glands and the stomach.

Stomach acid is strong and can dissolve most foods. But despite so much acid churning inside, the stomach itself remains intact. This is possible because the stomach is lined with a thick layer of protective mucus. Occasionally, this mucus layer is damaged—by a bacterial infection, for example—and the stomach lining becomes more vulnerable to gastric juices; the result is a painful sore called an ulcer.

While the stomach can absorb some substances, such as water, ethanol, and certain drugs, directly into the bloodstream, most of the chyme is pushed farther down the digestive tract, primarily into the small intestine, where it is further processed.

Although the stomach is only a small part of the upper digestive tract, it plays a large part in weight gain. Evolutionarily speaking, the reason we have a stomach in the first place is to enable us to store food. Without a stomach, we would have to eat constantly to fuel our activities. When we eat a large meal, the stomach expands greatly to accommodate and store all that food. It’s partly because of this elasticity that we can eat enough to sustain us for hours. But we can also eat more than our bodies need.