DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What structures make up the cardiovascular system, and how does blood flow through the system?

- What is the structure of the heart and of the different types of blood vessel?

- What is the composition of blood, and what does blood do?

- What is cardiovascular disease, and what are some of the risk factors for developing cardiovascular disease?

In-Class Activity

Click here to access Lecture ppt specifically designed for chapter 27.

Click here to access Clicker Questions specifically designed for chapter 27.

OME DIED IN CAR ACCIDENTS. OTHERS DROWNED, OR WERE STRICKEN with pneumonia. Still others were slain by bullets. The victims were as young as 2 and as old as 39. Together, they transformed our understanding of heart disease.

OME DIED IN CAR ACCIDENTS. OTHERS DROWNED, OR WERE STRICKEN with pneumonia. Still others were slain by bullets. The victims were as young as 2 and as old as 39. Together, they transformed our understanding of heart disease.

Some scientific discoveries begin in a laboratory. This one begins in a funeral home, in 1978. Under glaring lights, in the back room of the Cook-Richmond Funeral home in Bogalusa, Louisiana, two pathologists hover over the lifeless body of a young African-American male. There is no morgue in Bogalusa, so an autopsy is being conducted here, with newspapers spread beneath the body. The pathologists slice through skin and muscle with scalpels, looking for the usual suspects—internal bleeding, broken bones—then write up their report for the coroner.

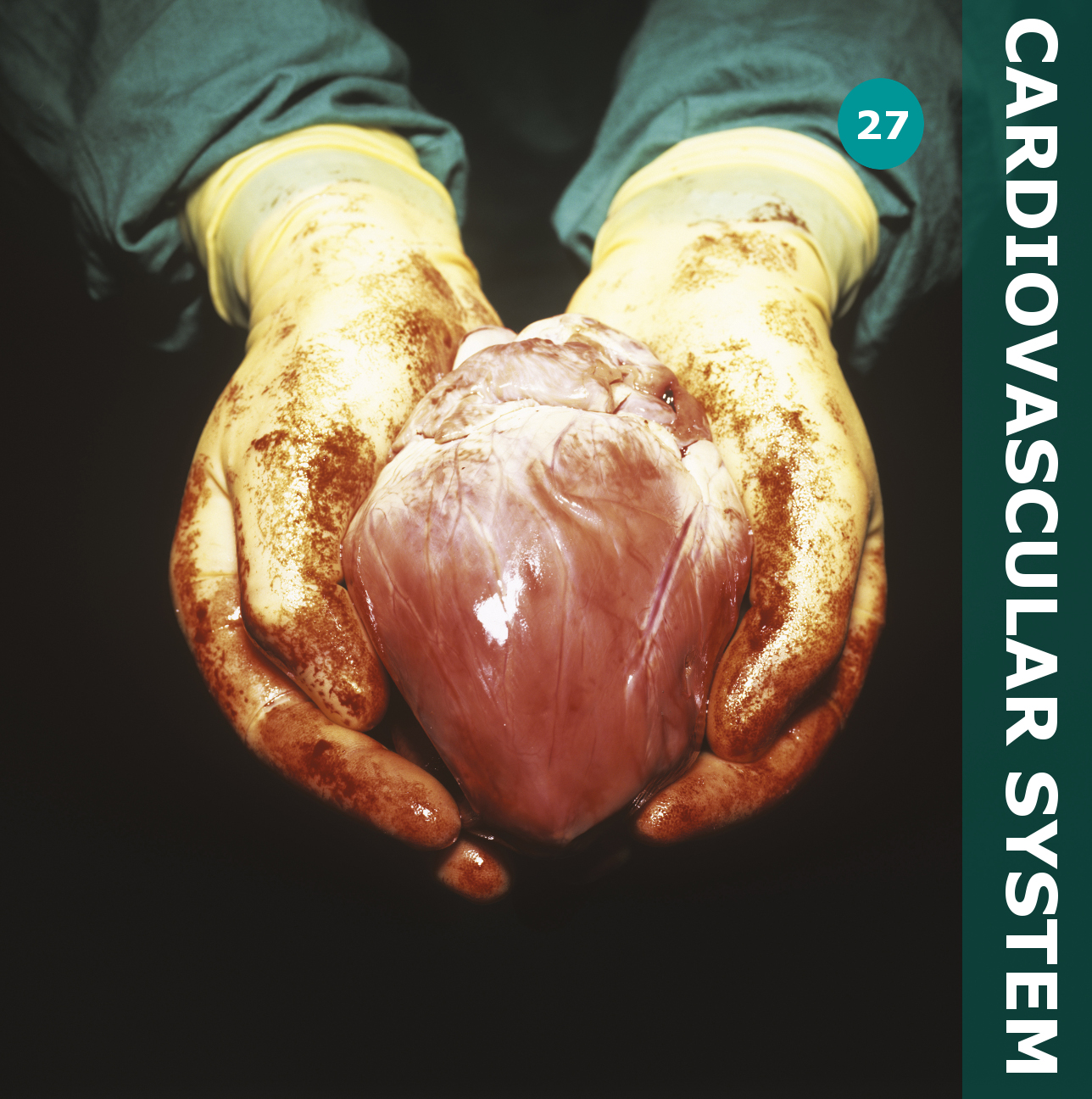

The pathologists aren't quite done, however. Before closing up, they carefully remove the victim's heart, package it in saline, and prepare it for a trip to a medical school in New Orleans. It was an unusual step, not standard for an autopsy. But the pathologists were heeding the instructions of a prominent local physician, who had the blessing of the family.

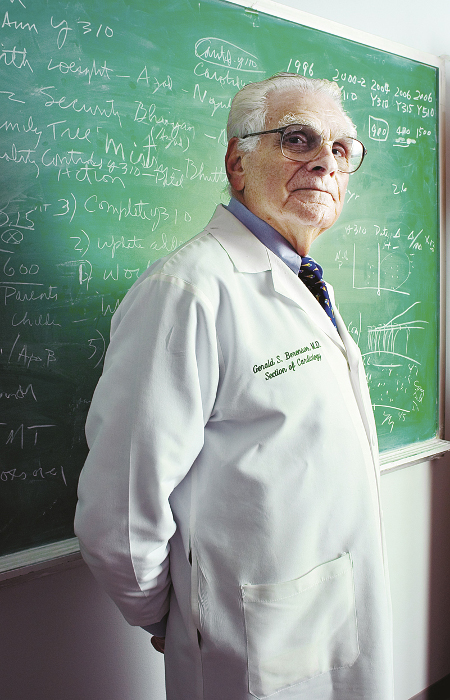

Gerald Berenson, a cardiologist with the Louisiana State University School of Medicine, had a passionate interest in heart disease. Since 1972, he had spearheaded what was then a novel study: an epidemiological study of heart disease in Bogalusa, a rural town of about 16,000 people located 60 miles north of New Orleans.

The study began with a pretty simple idea: follow a large group of children over a period of time and correlate their physical and lifestyle attributes with their risk for developing heart disease in adulthood. The biggest hurdle was a logistical one—how to enlist the thousands of children necessary to produce a robust data set, and keep them coming back for evaluation year after year.

But Berenson wanted to do more than make statistical correlations. He also wanted to document the progression of heart disease directly. And for that he needed a different type of evidence.

The heart that Berenson obtained in 1978 was one of more than 200 such organs collected from young people in Bogalusa over the next 20 years. In fact, nearly every young person who died, of whatever cause, was autopsied and had the heart removed. From this medical detective work has emerged a detailed understanding of heart disease in young people, and the evidence needed to clinch the case against a cold-blooded killer.