CURIOUS ABOUT CHEMISTRY

As one of the scientists behind Curiosity, McKay’s main job is figuring out the best way to look for life on Mars. He was part of the team responsible for packing Curiosity’s scientific toolkit.

In many ways, says McKay, Curiosity is the sequel to Viking, picking up where Viking left off. In terms of technological prowess, though, it’s light-years ahead. Curiosity is equipped with 10 scientific instruments, including a laser that can identify the chemical composition of rocks at a distance. It can also move around, which is a huge advantage over Viking.

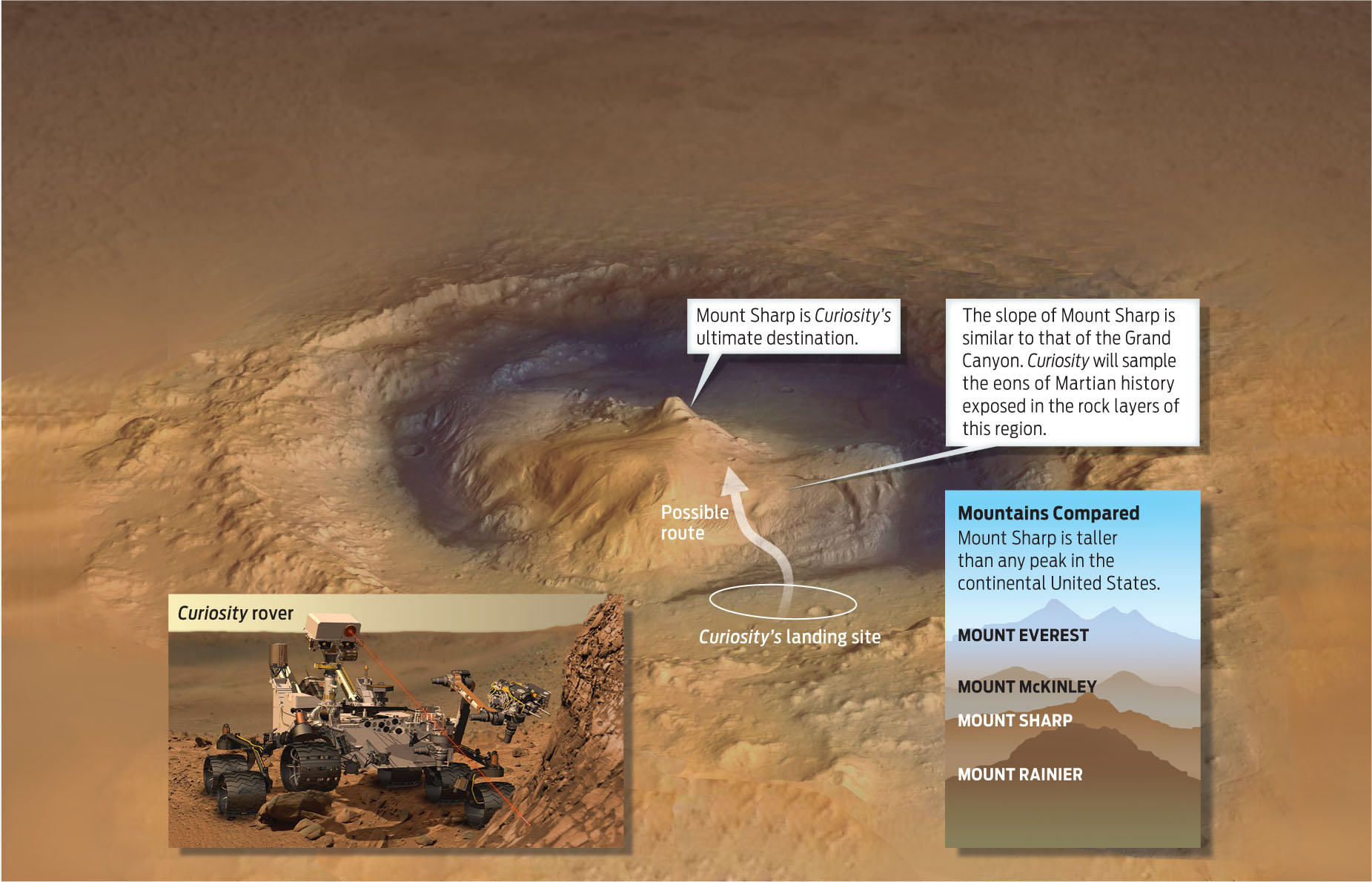

NASA set Curiosity down in a large canyon called Gale Crater. The rover’s ultimate destination, which it will travel to over weeks and months, is the slope of a steep peak dubbed Mount Sharp, located at the crater’s center. Geologically, the region is similar to the Grand Canyon, with exposed strata of past eons layered one on top of the other, like a many-layered cake. NASA thinks that this is the best spot to try to reconstruct the past history of Mars, as well as to look for signs of fossilized life-much in the way that scientists look for evidence of life in fossils that have been discovered in the clay and sandstone of the Grand Canyon (INFOGRAPHIC 2.2).

Curiosity set down in Gale Crater, and will navigate up Mount Sharp, where it will look for evidence of life.

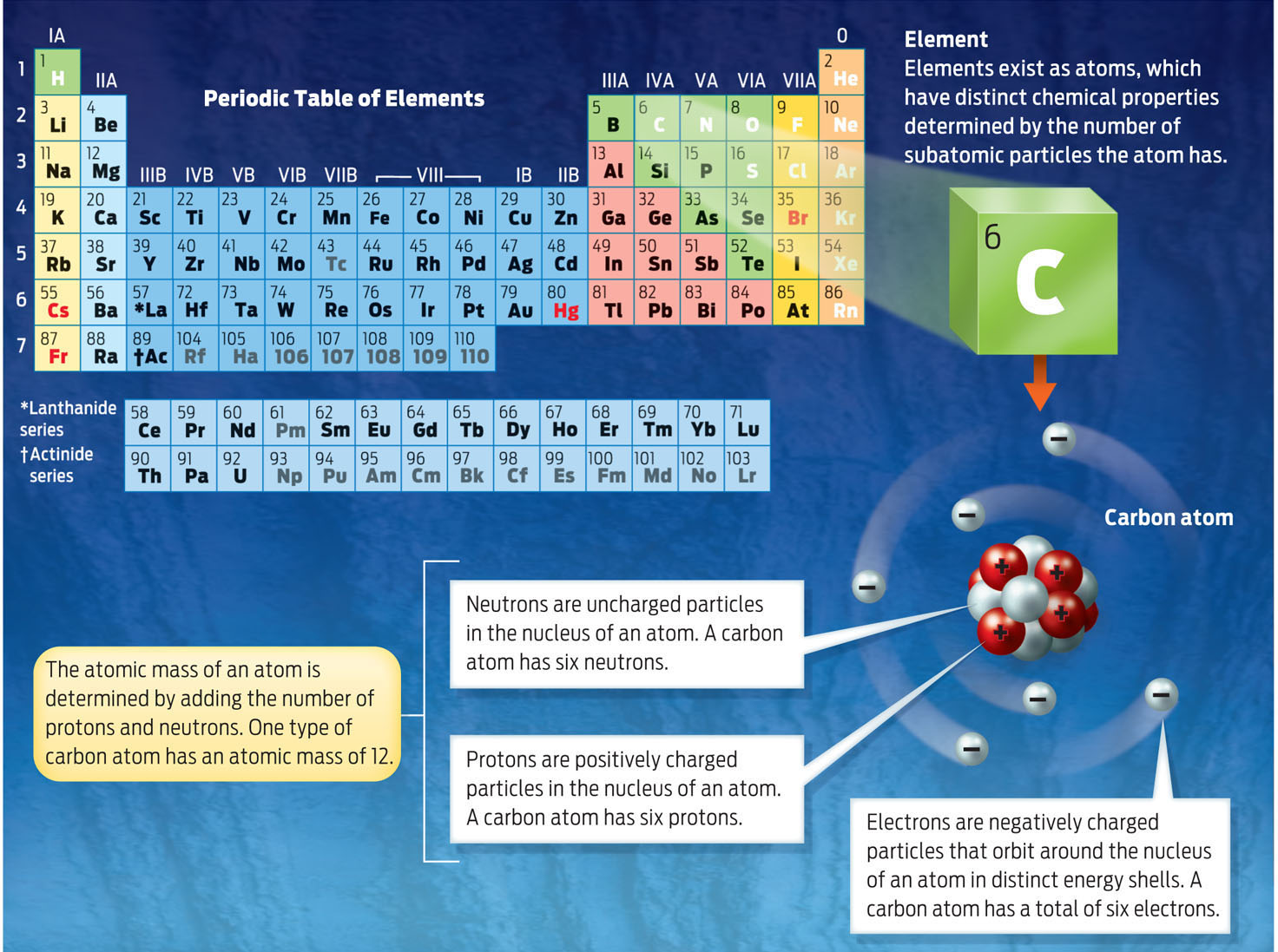

ELEMENT A chemically pure substance that cannot be chemically broken down; each element is made up of and defined by a single type of atom.

Unlike Viking, Curiosity will not actually test for living organisms (by monitoring carbon dioxide emissions, for example). Instead, it will look for other evidence of life: the chemical building blocks necessary to assemble it.

MATTER Anything that takes up space and has mass.

All life we know of-from amoeba to zebra-uses the same basic chemical recipe: a stew of carbon-based ingredients floating in a broth of water. Carbon (C) is one of approximately 100 different elements in the universe. Elements are substances that cannot be broken down by chemical means into smaller substances. They are themselves considered the fundamental components of anything that takes up space or has mass-the matter in the universe. Elements make up both living and nonliving things. The rocky surface of Mars, for example, appears red because of an abundance of the element iron (Fe) that has long since rusted.

ATOM The smallest unit of an element that cannot be chemically broken down into smaller units.

PROTON A positively charged subatomic particle in the nucleus of an atom.

The smallest unit of an element that still retains the property of that element is an atom. What gives each atom its identity is its specific number of positively charged protons, negatively charged electrons, and neutral neutrons. A carbon atom, for example, has six protons, six electrons, and six neutrons. The relatively heavy protons and neutrons are packed into the atom’s dense core, or nucleus, while the tiny electrons orbit around it (INFOGRAPHIC 2.3).

ELECTRON A negatively charged subatomic particle with negligible mass.

NEUTRON An electrically uncharged subatomic particle in the nucleus of an atom.

NUCLEUS The dense core of an atom.

The periodic table of elements represents all known elements in the universe. Each element is placed in order on the table by its atomic number, the number of protons found in the nucleus of its corresponding atom.

Carbon is the fourth most common element in the universe and the second most common element in the human body. In fact, just six elements make up the bulk of you: oxygen (65%), carbon (18%), hydrogen (10%), nitrogen (3%), calcium (1.5%), and phosphorus (1%).

We don’t see any other element that has the sort of flexibility and utility that carbon has.

We don’t see any other element that has the sort of flexibility and utility that carbon has.

— CHRIS MCKAY

When astrobiologists (and science fiction writers) talk about “carbon-based life forms,” they are referring to the fact that carbon forms the backbone of nearly every chemical making up living things. Just as humans have a backbone made of a chain of interconnected vertebrae, the chemicals making up living things have a backbone of interconnected carbon atoms. The backbone can be linear, like our spine, or circular-in which case the first carbon in the chain binds to the last carbon in the chain.

“Carbon is very cool, very flexible, very useful,” says McKay. “We don’t see any other element that has the sort of flexibility and utility that carbon has.” That’s the main reason why scientists are so interested in it.