DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What is the structure of a virus, and how do viruses cause disease?

- What is innate immunity?

- What is adaptive immunity, and how does vaccination rely on adaptive immunity?

- What are specific features of influenza virus that allow it to cause worldwide outbreaks?

In-Class Activity

Click here to access Lecture ppt specifically designed for chapter 31.

Click here to access Clicker Questions specifically designed for chapter 31.

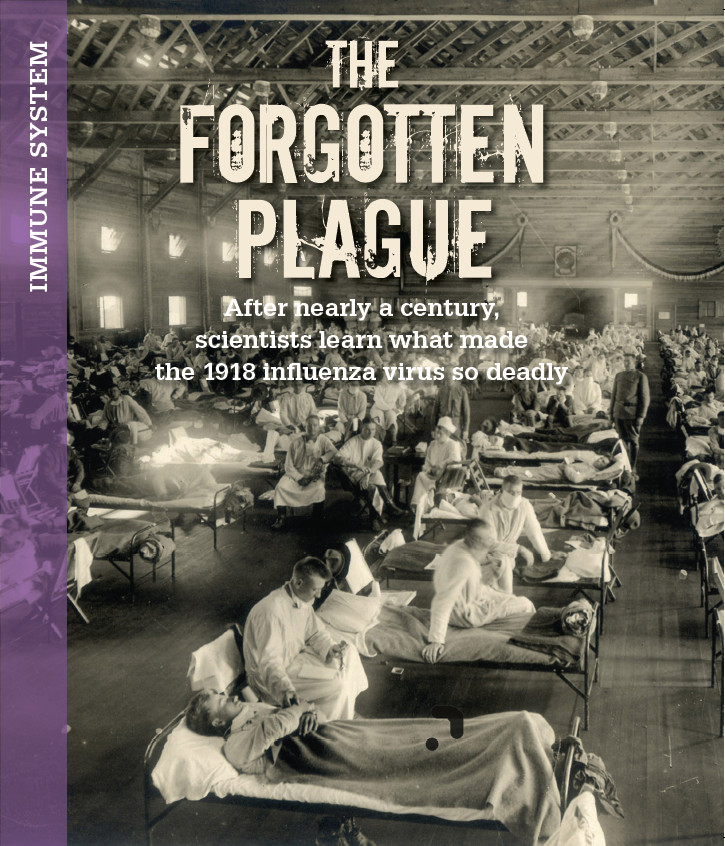

N THE FALL Of 1918, WORLD WAR I WAS COMING TO AN END—but another, insidious, threat was surfacing. In communities around the world, a deadly illness was gaining momentum, spreading like wildfire from person to person.

N THE FALL Of 1918, WORLD WAR I WAS COMING TO AN END—but another, insidious, threat was surfacing. In communities around the world, a deadly illness was gaining momentum, spreading like wildfire from person to person.

At first the disease seemed much like a bad case of influenza, or “flu.” High fevers and body aches were common. But some patients also developed more severe symptoms, such as coughing so intense that they spat up blood. Many died so quickly after falling ill that doctors began to suspect they were witnessing something far worse than ordinary flu.

Stories were told of victims who were completely healthy in the evening but were dead by morning. An army physician stationed at Camp Devens in Massachusetts wrote to a friend that patients with what seemed like ordinary flu would rapidly “develop the most vicious type of pneumonia that has ever been seen” and later would “struggle for air until they suffocated.” Patients “died struggling to clear their airways of a blood-tinged froth that sometimes gushed from their nose and mouth,” recalled Isaac Starr, a physician who was a third-year medical student in Philadelphia during the war and who published his recollections of the illness in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 1976.

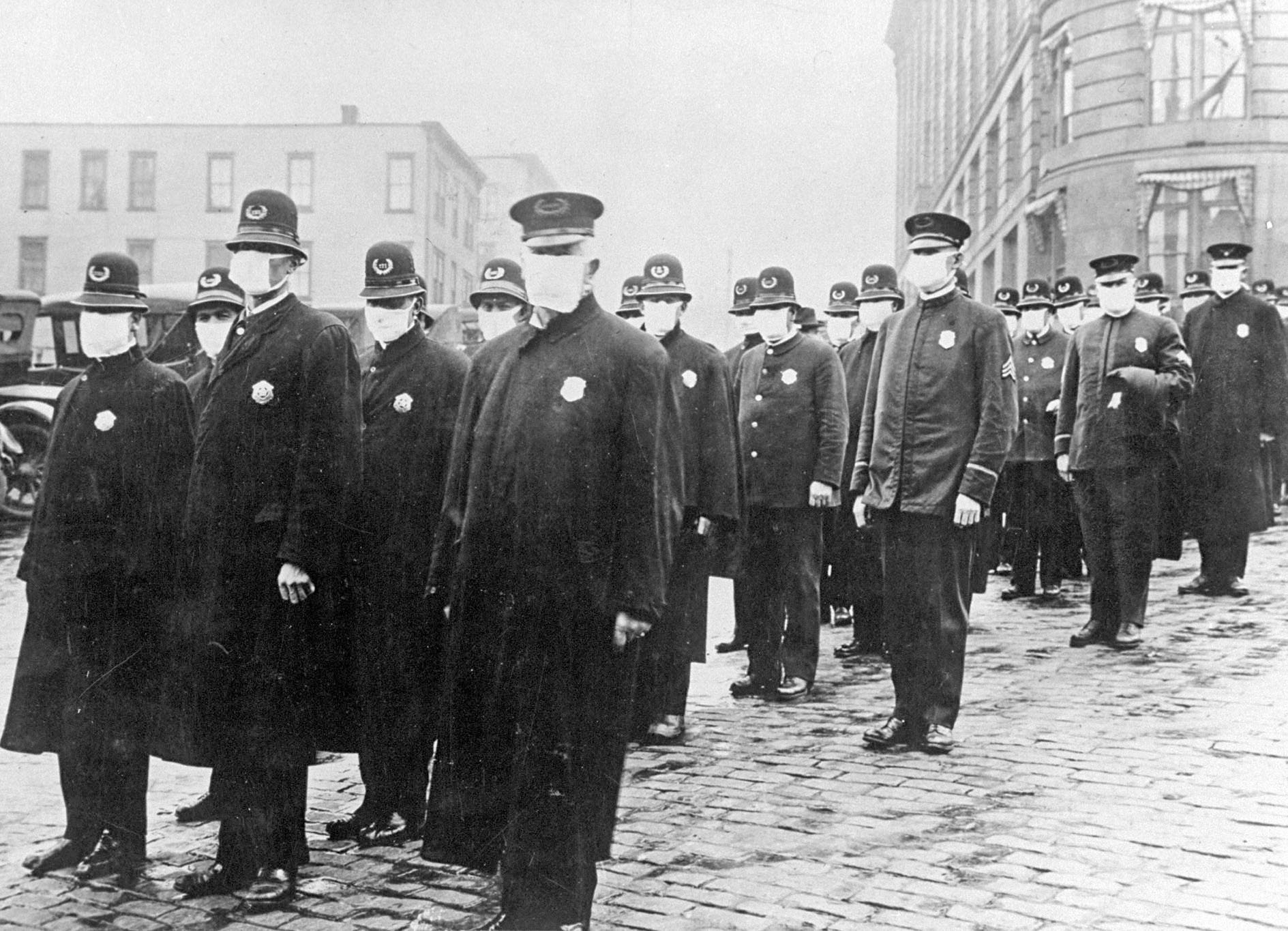

Between 1918 and 1920, the disease swept around the globe. Had the world not been at war, the pandemic might never have happened. Troops carried the illness with them across Europe and back to the United States, infecting relatives, friends, and strangers along the way.

The result was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. According to historian John Barry, the 1918 flu pandemic killed more people in 1 year than the Black Death killed in the 14th century; it killed more people in 25 weeks than AIDS has killed in 25 years. By the time it was over, between 50 and 100 million people around the world had perished–more than the total number killed in World War I.

Why this particular strain of flu inflicted so much more devastation than any pandemic that came before or after, scientists of the time couldn’t say. For decades after the pandemic had subsided, it seemed it would never be possible to explain the flu’s severity, since the virus itself was lost to history. But recent discoveries have made it possible to peer into the viral past, and scientists have begun to uncover what made the 1918 virus so deadly.

The 1918 flu pandemic killed more people in 1 year than the Black Death killed in the 14th century; it killed more people in 25 weeks than AIDS has killed in 25 years.