IMMUNOLOGICAL MEMORY

Not everyone who became infected with the 1918 flu died, despite its virulence. In fact, while there were approximately 50 to 100 million deaths, experts estimate that some 525 million people were infected–about 30% of the entire world population. How so many people were able to fight the infection while others died remains mostly a mystery. But scientists do have some clues.

Of those who became infected and then recovered, some may have had partial immunity from an earlier infection. Such long-lasting immunity is conferred by the adaptive immune system.

B CELLS White blood cells that mature in the bone marrow and produce antibodies during the adaptive immune response.

Whereas the innate immune system is always ready to fight, the adaptive immune system must be primed over time. From birth into adulthood, our bodies are continuously assaulted by a barrage of pathogens. With repeated exposure, our bodies develop a memory of every pathogen we encounter that gets past our innate defenses. Should we confront the same pathogen again, immunological memory helps our bodies fight off infection before it can take hold.

THYMUS The organ in which T cells mature.

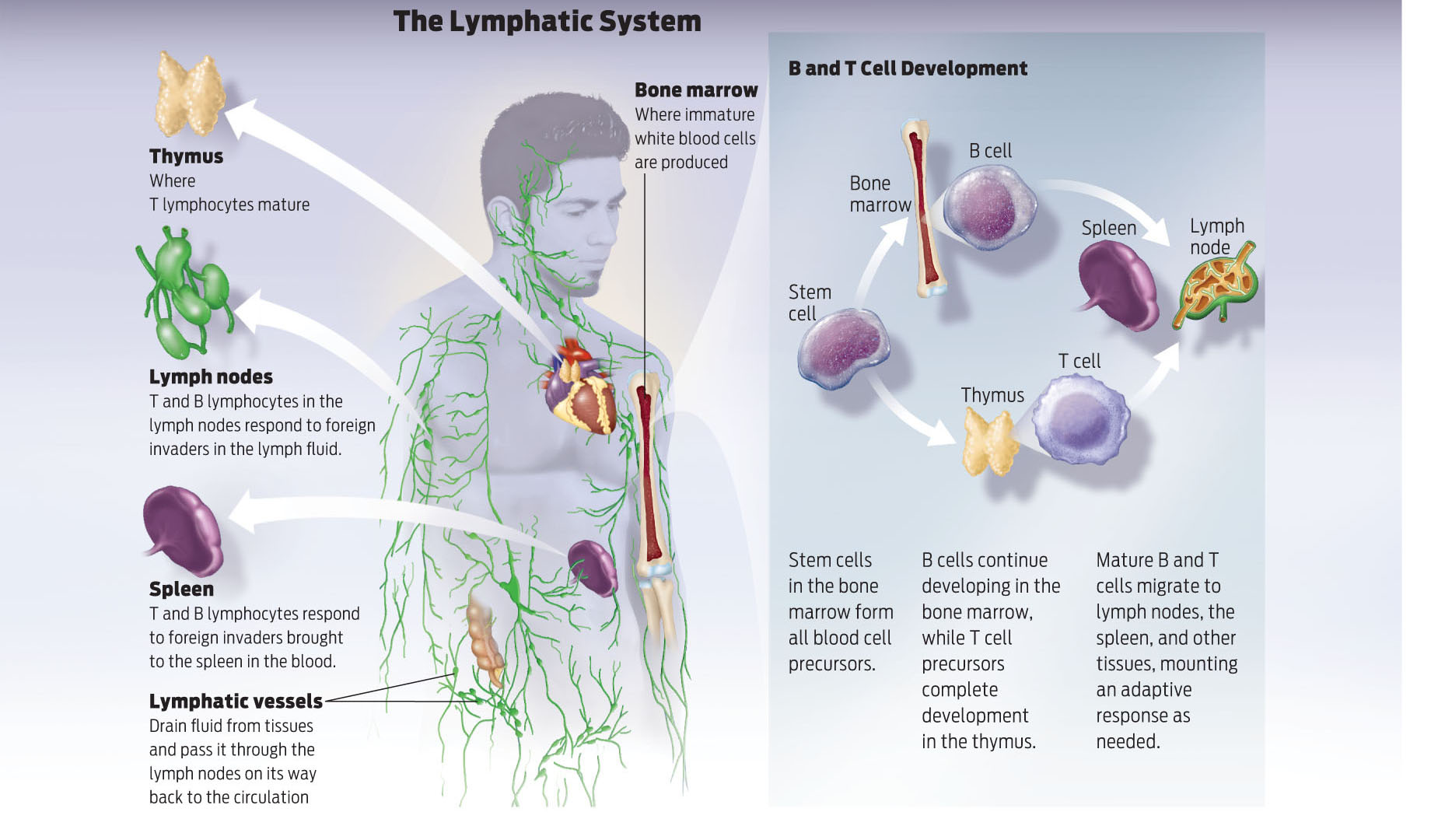

Two types of lymphocyte play crucial roles in adaptive immunity: B cells and T cells. Like all blood cells, B and T cells develop from precursor cells made in the bone marrow. Some immature lymphocytes in bone marrow become B cells (think “B” for “bone”). Other lymphocytes migrate from the bone marrow to the thymus, a gland in the chest, where they become T cells (think “T” for “thymus”). Both B cells and T cells eventually travel to the lymph nodes and other organs of the lymphatic system, where they hunt for pathogens (INFOGRAPHIC 31.6).

T CELLS White blood cells that mature in the thymus and can destroy infected cells or stimulate B cells to produce antibodies, depending on the type of T cell.

LYMPH NODES Small organs in the lymphatic system where B and T cells may encounter pathogens.

LYMPHATIC SYSTEM The system of vessels and organs that works with the immune system, allowing B and T cells to respond to pathogens.

The immune system is made up of specialized cells called lymphocytes that develop, mature, and act in a variety of tissues, including the bone marrow, thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes, which are part of the lymphatic system.

HUMORAL IMMUNITY The type of adaptive immunity that fights free-floating pathogens in the blood and lymph fluid.

ANTIBODY A protein produced by B cells that binds to antigens and either neutralizes them or flags other cells to destroy pathogens.

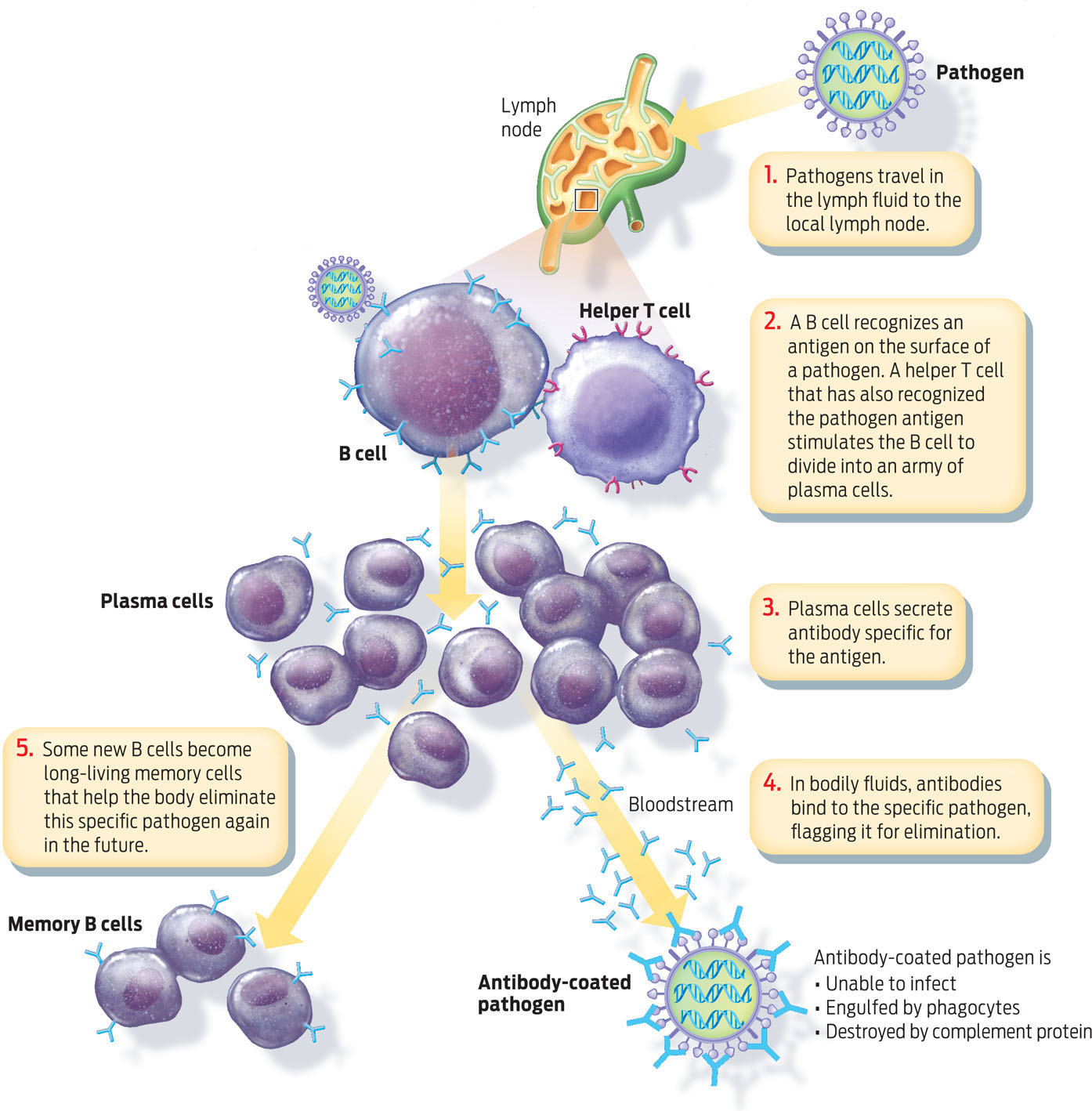

B and T cells cooperate to produce two main types of adaptive immunity. One type, called humoral immunity, targets free-floating pathogens in body fluids (“humoral” refers to the “humors,” an old name for the liquids in the body). Humoral immunity produces antibodies–proteins that circulate in body fluids and help to fight infections. Antibodies are produced by B cells, but specialized T cells called helper T cells are needed to jumpstart the process. Both B cells and helper T cells recognize bacterial and viral antigens, which are specific identifying structures on the surface of pathogens. Antigens are like unique molecular fingerprints, alerting the immune system to the presence of invaders. When a B cell and a helper T cell recognize the same antigen, the B cell becomes activated. That B cell will divide repeatedly to create an army of plasma cells–cells that secrete many copies of an antibody specific to that particular antigen. Some of the plasma cells will become memory cells, which remain the bloodstream and “remember” the infection; they can be called on in the future to secrete antibodies in response to an infection.

HELPER T CELL A type of T cell that helps activate B cells to produce antibodies.

ANTIGEN A specific molecule (or part of a molecule) to which specific antibodies can bind, and against which an adaptive response is mounted.

PLASMA CELL An activated B cell that divides rapidly and secretes an abundance of antibodies.

MEMORY CELL A long-lived B or T cell that is produced during an immune response and that can “remember” the pathogen.

Antibodies fight infections in several ways. First, by binding to antigens, they may physically block the infectious organism from infecting other cells, rendering it harmless. Second, they can flag a pathogen to be digested by phagocytes. Finally, they can mark the pathogen so that complement proteins will bind to it and destroy it. In other words, antibodies that bind to antigens are like giant red flags, alerting the body’s immune system to take action.

Each B cell produces only one type of antibody. And antibodies produced against one antigen are usually ineffective against any other antigen—they are highly specific. But because the body can produce more than a billion unique B cells, there are that many different kinds of potential antibodies—a very large war chest indeed (INFOGRAPHIC 31.7).

B cells and helper T cells recognize antigens on pathogens that are free-floating between cells. When a B cell and a helper T cell recognize the same antigen, the T cell can activate the B cell to divide and become plasma cells. Plasma cells secrete antibodies that bind specifically to antigens on pathogens to inactivate and destroy them. Specific memory B cells are also produced and spring into action if the same pathogen is encountered again in the future.

CELL-MEDIATED IMMUNITY The type of adaptive immunity that rids the body of infected, cancerous, or foreign cells.

CYTOTOXIC T CELL A type of T cell that destroys infected, cancerous, or foreign cells.

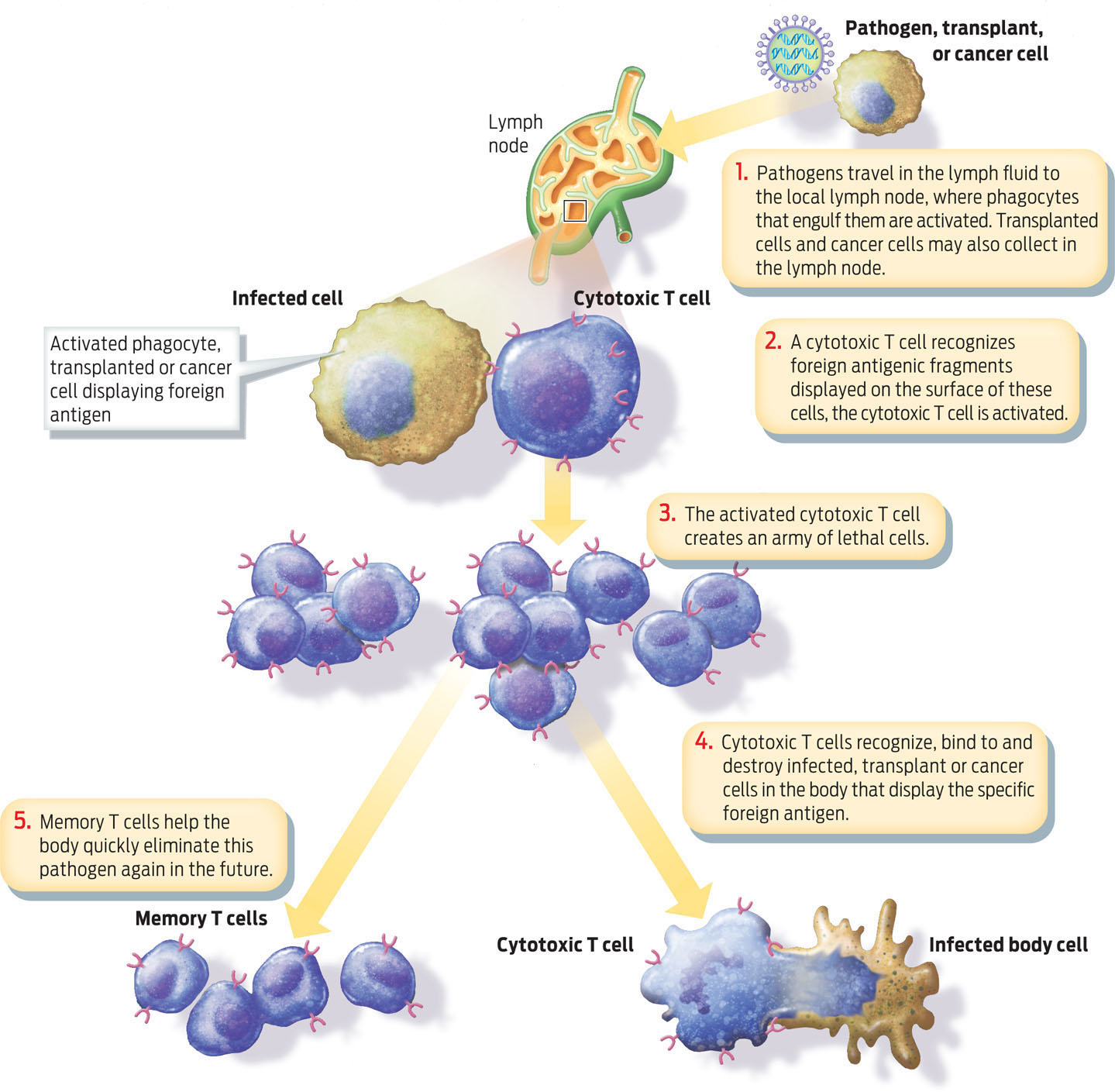

The second type of adaptive immunity, called cell-mediated immunity, targets infected or altered body cells. This response requires a type of T cell called a cytotoxic T cell. Cytotoxic T cells are activated by foreign (viral or bacterial) antigens on the surface of phagocytes that have engulfed pathogens. Helper T cells can also help activate cytotoxic T cells. The activated cytotoxic T cells then patrol the body, on the lookout for infected cells displaying these distinguishing antigens. In addition to infected body cells, cytotoxic T cells also target foreign cells (from a transplanted organ or tissue, for example) and even cancer cells that the body recognizes as altered. The activated cytotoxic T cells bind to antigens on these target cells and release cytotoxic chemicals that cause the rogue cells to self-destruct (INFOGRAPHIC 31.8).

Cytotoxic T cells can be activated by cells displaying foreign (viral or bacterial) antigen on their surface. They can also be activated by cells of a transplanted organ and cancer cells. Cytotoxic T cells bind to these altered cells and release chemicals that destroy them. They also divide to produce memory cytotoxic T cells.

Note that while both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses destroy invading pathogens, there is a key difference between them: humoral immunity acts by releasing antibodies that bind to antigens on free-floating pathogens in lymph and blood; in a cell-mediated immune response, cytotoxic T cells bind to and destroy infected or altered cells in body tissues.

ALLERGY A misdirected immune response against environmental substances such as dust, pollen, and foods that causes discomfort in the form of physical symptoms.

With its billions of potential lymphocytes, each adapted to recognize a particular antigen, the adaptive immune system enables our bodies to fight off countless numbers of pathogens. Occasionally, however, for reasons that are not entirely clear, the system runs amok and immune cells become active even against antigens that aren’t harmful to us, or worse, they begin attacking healthy cells in the body.

AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE A misdirected immune response in which the immune system attacks healthy cells.

When the immune system attacks harmless antigens from outside the body, like dust or certain types of food, an allergy is the result. Allergies are quite common, often accompanied by a runny nose, watery eyes, and sneezing—all triggered by histamine, the same chemical involved in inflammation. When the immune system attacks the body’s own healthy cells, a more serious autoimmune disease can result. Multiple sclerosis, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis are all autoimmune diseases, caused by a body at war with itself.