BUILDING A LINE OF DEFENSE

PRIMARY RESPONSE The adaptive response mounted the first time a particular antigen is encountered by the immune system.

SECONDARY RESPONSE The rapid and strong response mounted when a particular antigen is encountered by the immune system subsequent to the first encounter.

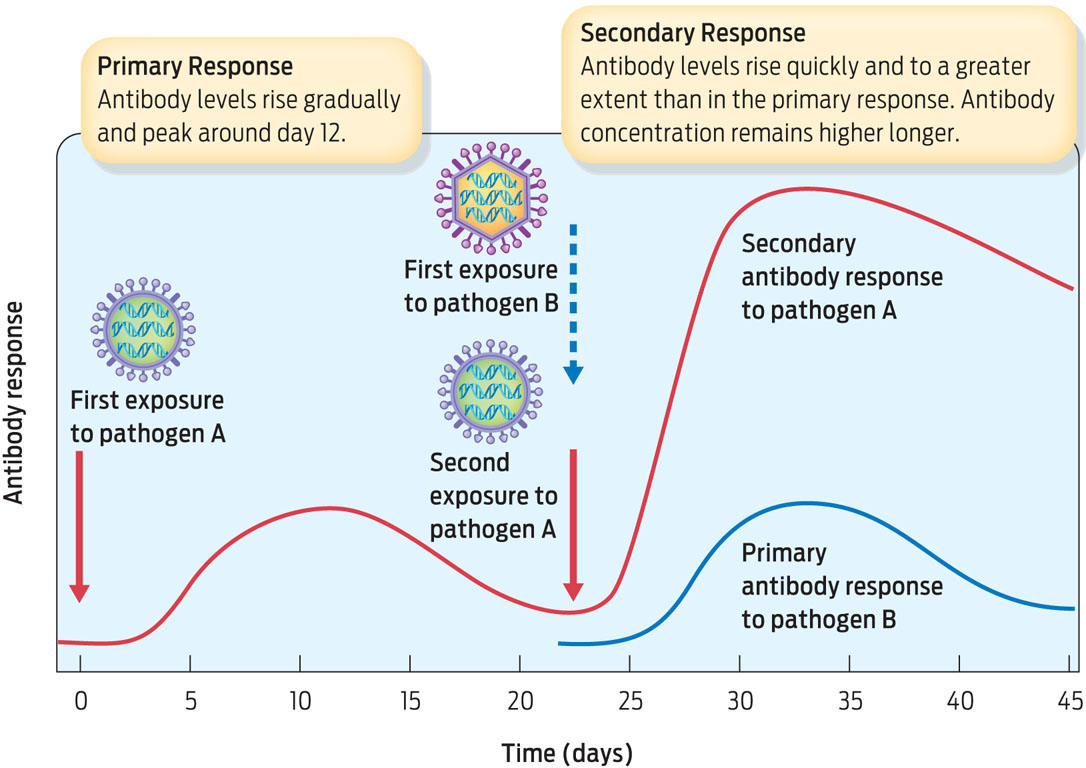

The advantage of adaptive immunity is that it learns to respond to new invaders and targets them specifically. The downside is that it takes a while for it to kick in. First-time exposure to a pathogen will almost certainly cause illness, because the adaptive response takes 7 to 10 days to develop. Over time an exposed individual will recover as T and B cells are activated and antibody levels increase. This initial slow response is the primary response. As B and T cells are churned out, some of them become memory cells. These memory cells remain in the bloodstream and “remember” the infection. The next time the same pathogen is encountered, memory B and T cells become active, dividing rapidly and leading to the production of very high levels of antibodies. They fight the specific pathogen so quickly that the illness usually doesn’t occur a second time. This rapid reaction is called the secondary response (INFOGRAPHIC 31.9).

The adaptive immune system’s primary humoral response is slow and produces low levels of antibodies. Upon subsequent exposures, memory cells produced during the primary response respond quickly and trigger B cells to produce high levels of antibodies. This secondary response is so rapid and effective that illness does not occur. The secondary response of cell-mediated immunity and cytotoxic T cells is also quick and effective.

VACCINE A preparation of killed or weakened microorganisms or viruses that is administered to people or animals to generate an immune response.

The secondary response is what confers immunity to a particular infection. It’s also how vaccines work. Vaccines are essentially dead or weakened versions of a pathogen administered to a patient to elicit an immune response. The goal is to create a primary response in the body that’s strong enough to create memory cells, yet weak enough so as not to cause disease symptoms. Thus, if the pathogen is subsequently encountered naturally, the secondary response is already primed. Vaccination is like being infected with a pathogen but not having the disease.

Similarly, people exposed to a pathogen that is similar to a pathogen with which they were previously infected may be partly protected from the disease caused by the new pathogen. Memory B and T cells may still respond, although only partially–in which case the illness may occur, but mildly.

Evidence suggests that such partial immunity may have helped some of those infected survive the 1918 flu pandemic. Statistical data from the time show that people over 65 accounted for the fewest influenza cases, suggesting that they might over the years have acquired immunity or partial immunity from earlier infection. Partial immunity might have helped these people fight off the virus before it dug deep into the lungs.