Plant Reproduction

Do plants have sex?

Do plants have sex?

STAMEN The male sexual organ of a flower.

ANSWER: They may not go on blind dates or join online dating sites, but plants are among the most “flirtatious” and sexually active organisms on earth. The many bright colors, provocative shapes, and alluring fragrances of flowers are the plant equivalents of lipstick, muscle shirts, and perfume—evolutionary novelties designed to attract pollinating partners.

POLLEN Small, thick-walled structures that contain cells that will develop into sperm.

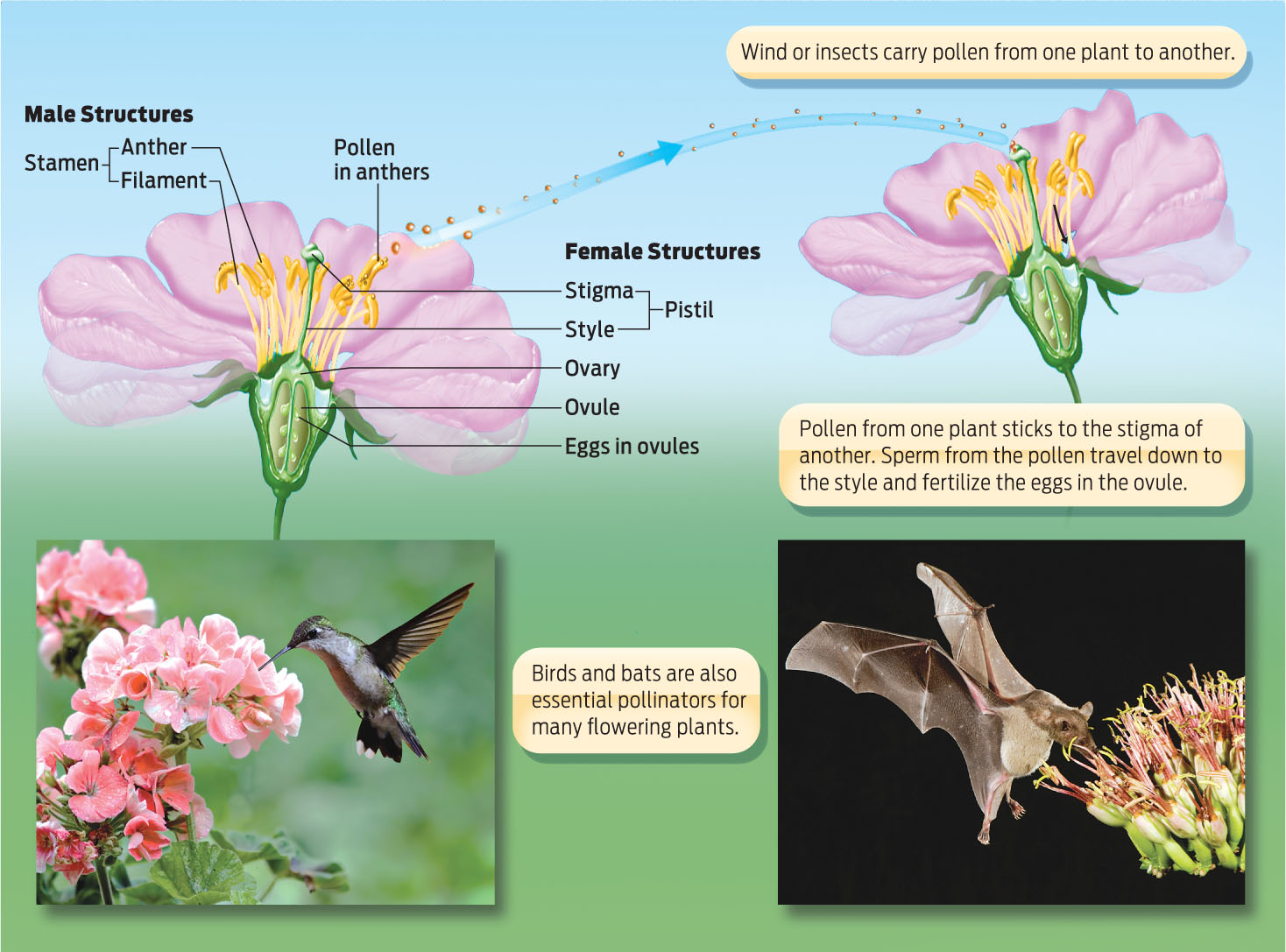

Like other sexually reproducing creatures, plants have distinct male and female reproductive organs that produce haploid gametes: sperm and egg. In flowering plants, male and female sexual organs are housed within a plant’s flowers. The male sexual organ, called the stamen, consists of a stalklike filament that supports a structure, the anther, that contains pollen. Pollen grains contain cells that will develop into sperm. The female structure, called a pistil, consists of a tubelike structure (called the style) topped with a sticky stigma, a “landing pad” for pollen. At the base of the pistil is a plump ovary stuffed with egg-containing ovules. Transfer of pollen from a male stamen to a female pistil results in pollination, which may then lead to fertilization. To fertilize eggs, sperm from the pollen must travel down the pistil to the ovary, where the eggs are located. When a haploid sperm fuses with a haploid egg, the result is a diploid plant zygote, which divides to form the embryo.

PISTIL The female reproductive organ of a flower.

POLLINATION The transfer of pollen from a male stamen to a female pistil.

727

In some flowering plant species, male and female organs are found on separate male and female plants. Ginkgo trees and holly bushes are examples of such unisexual plants. More commonly, however, flowering plants—everything from dandelions to lilies—are hermaphrodites: their flowers contain both male and female reproductive parts. A few such hermaphroditic plants can self-pollinate—transferring pollen from stamen to pistil within the same flower or plant. But most hermaphroditic plants have evolved ways to prevent self-pollination and to encourage out-crossing instead. They may have pistils and stamens of different heights, for example, or their pollen may be chemically rejected by eggs of the same plant.

Plants have evolved many elaborate ways to spread their pollen from plant to plant. For many flowering plants, pollinators such as bees and hummingbirds transfer pollen grains from the anther of one flower to the stigma of another. To these animal pollinators, a flower’s scent is a potent aphrodisiac, irresistibly attracting them to the blossom. Other plants rely on wind to transfer pollen (INFOGRAPHIC 32.6).

In the flowering plants, pollen grains produced by male flower parts land on female flower parts, where fertilization occurs.

Not all plants are so sexually adventurous. Some are asexual, or have asexual phases, and can produce new individuals through underground root runners or bulbs that develop into whole new plants. Asexual reproduction, in the form of cuttings and grafting, is especially important in agriculture. A cutting taken from one plant can be planted in soil to form a new plant; sugar cane and pineapples are often reproduced this way. A cutting taken from a plant can also be surgically grafted to the root system of a different plant—a procedure commonly used to perpetuate vineyard grapes.

728