EMPTYING THE WARDS

By the time Manary began seriously thinking about home–based therapy, he had been working in Malawi for about 5 years, witnessing the failure of the standard WHO treatment, and he had spent time in villages. In his head, he'd been tossing around the idea of something new and different. Out of the blue, he got an e–mail from a doctor in France, André Briend, who was also thinking about home–based therapy as a treatment for malnutrition.

The two scientists corresponded for about a year by e–mail, weighing the pros and cons of various foods that could be eaten at home yet still pack a nutrient wallop. After considering various options—they considered biscuits, pancakes, even Nutella—the two researchers eventually decided on peanut butter as the best choice. In 2001, they decided to test the idea.

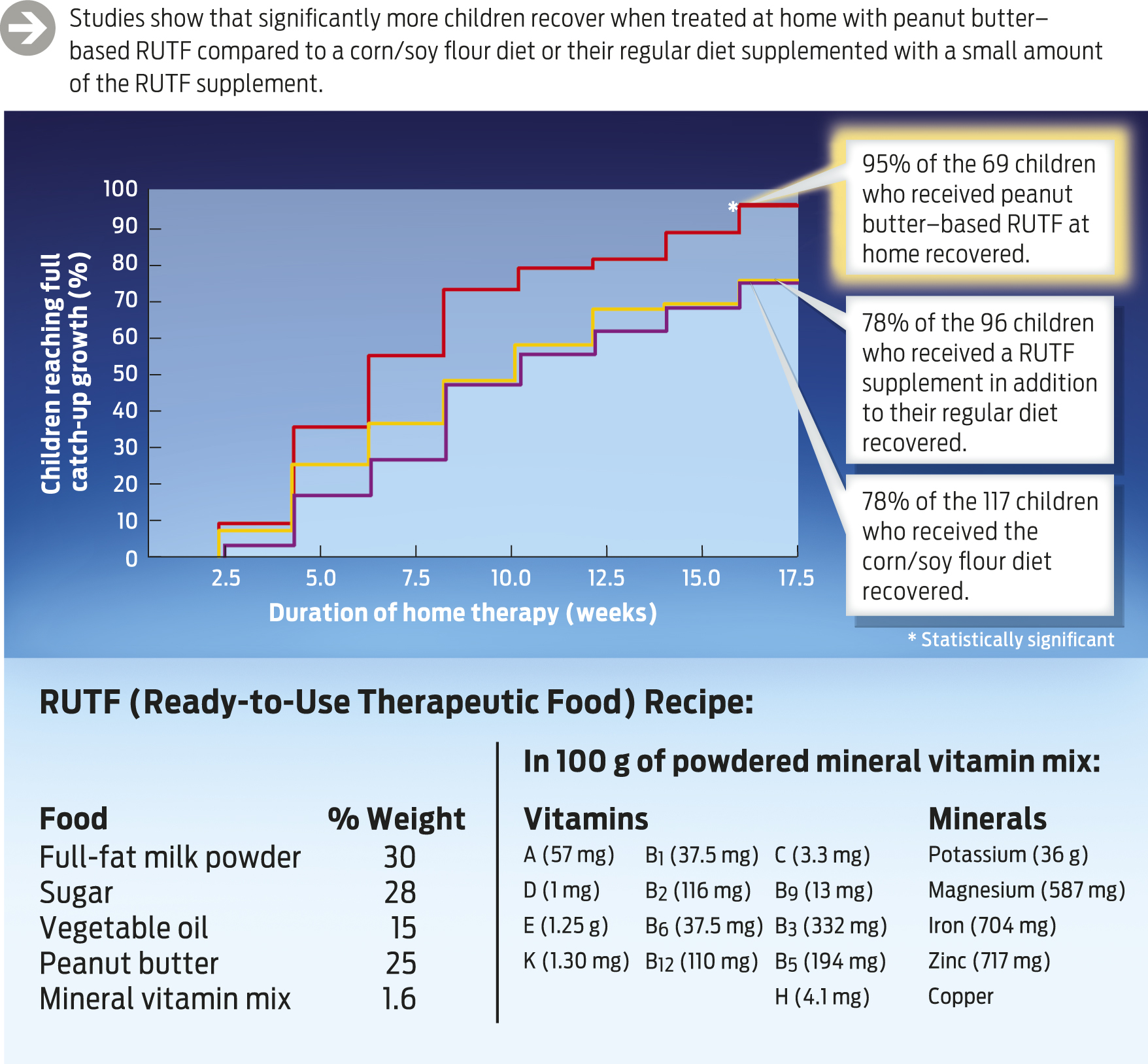

Briend had some of the peanut butter RUTF made up in France and then sealed in foil packets and shipped to Malawi. They then used this product in a carefully designed scientific study. After a brief stabilization phase in the hospital (during which antibiotics were given, if necessary), the children were discharged and sent home on one of three different treatment regimens: (1) ample amounts of traditional food—corn flour and soy; (2) a small amount of peanut butter–based RUTF, to be used as a supplement to the normal diet at home; and (3) the full dose of peanut butter–based RUTF, with sufficient nutrients to meet the total nutritional needs of the children. The goal of the study was to see which treatment regimen was most effective.

Within a few months, the results were astonishing: 95% of the children who received the full peanut butter–based RUTF recovered. Those who received traditional food also did pretty well—about 75% of them recovered, but still the peanut butter was better. And all the home-based treatments were significantly better than standard hospital-based milk therapy, which historically had a 25%–40% recovery rate.

Manary couldn't quite believe how effective the treatment was. “I said, “Damn, this stuff really works!'” (INFOGRAPHIC 4.7).

One of the main reasons that peanut butter RUTF—which locals call chiponde, or “nutpaste”—is more effective than standard therapy is that it can be administered safely at home. When children are malnourished, their immune systems aren't functioning at optimal levels, which means that hospitals are often the worst place for them to be because of the risk of infection from other sick patients. Peanut butter RUTF is also something that children can eat on their own, without help from their parents. And, because they clearly like the taste of it (one doctor described it as tasting like the inside of a Reese's Peanut Butter Cup), they gobble it up.

As dramatic as Manary's initial results were, however, not everyone was convinced. In fact, most leaders in nutrition science were vehemently opposed to the approach, which is why Manary was heckled at the conference in 2003.

Manary wasn't the only person in the field to face a backlash. Other doctors working in this area faced similar opposition. “It was pretty nasty,” says Steve Collins, a physician and early advocate of home-based treatment, whose work was also lambasted.

At that time, around 2003, the conventional wisdom in humanitarian aid circles was that these children were so sick that they needed to be hospitalized so that doctors and nurses could take care of them. But doctors who, like Manary, were working in the trenches, knew differently. They knew that even with the best available treatments—administered with careful precision by trained professionals—children were recovering only 25%–40% of the time. And, as Manary showed, mothers who were sent home with RUTF could do much better.

To raise awareness of his peanut butter approach and to start making the treatment available on a wider basis, in 2004 Manary started Project Peanut Butter, which would produce the product locally and distribute it to families in Malawi. So far, he says, more than 500,000 kids have been helped by peanut butter RUTF—not only in Malawi, but all across the world, including in Haiti and Sierra Leone.

Within a few months, the results were astonishing: 95% of the children who received the full peanut butter–based RUTF recovered.

Thanks in part to Project Peanut Butter, and the extensive body of evidence that Manary and others have collected, the world aid community eventually came around to Manary's view: in 2007, in a dramatic about-face, the joint UN relief agencies—UNICEF, WHO, and the World Food Programme—issued an official statement saying that home-based therapy with peanut butter RUTF is the preferred way to treat acute malnutrition. Manary's approach was vindicated.