DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- When and how does normal cell division occur in the body?

- How do normal cells and cancer cells differ with respect to cell division?

- How are cancer treatment decisions made for a given patient?

- How are new cancer drugs developed?

In-Class Activity

Click here to access Lecture ppt specifically designed for chapter 9.

Click here to access Clicker Questions specifically designed for chapter 9.

N 1988, DOCTORS AND PATIENTS HAILED THE DISCOVERY OF A powerful new cancer-fighting drug then making its way through clinical trials. Known as taxol, the drug had remarkable effectiveness in treating advanced ovarian cancer. Some 30% of women with ovarian cancer who took taxol saw their tumors shrink, even after other drugs had failed to have any effect. Two years later, taxol was found to be even more effective at treating breast cancer: 50% of patients saw their tumors regress.

N 1988, DOCTORS AND PATIENTS HAILED THE DISCOVERY OF A powerful new cancer-fighting drug then making its way through clinical trials. Known as taxol, the drug had remarkable effectiveness in treating advanced ovarian cancer. Some 30% of women with ovarian cancer who took taxol saw their tumors shrink, even after other drugs had failed to have any effect. Two years later, taxol was found to be even more effective at treating breast cancer: 50% of patients saw their tumors regress.

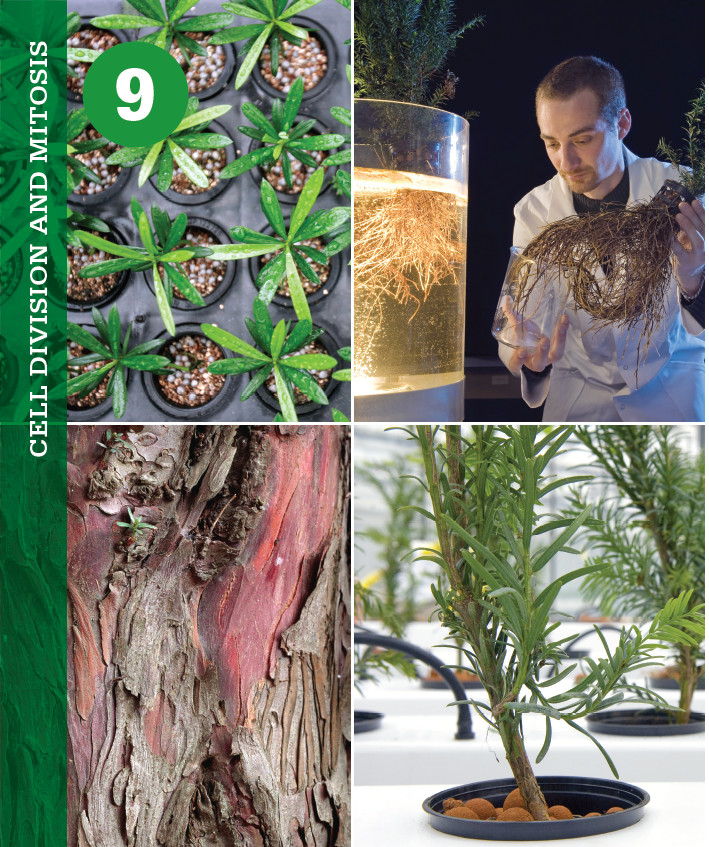

For all these women, taxol was a lifesaver, and demand for the drug skyrocketed. There was just one problem: taxol was isolated from the bark of the pacific yew tree, found only in old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest. If every woman with ovarian cancer who needed the drug got it, it would mean harvesting 1.3 million pounds of bark and killing 360,000 trees. Add in the trees required to treat patients with breast cancer, and the numbers were staggering.

“You needed the bark from a fairly good-sized tree to treat one woman with breast cancer,” says Susan Band Horwitz, a molecular pharmacologist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, whose work helped bring taxol to the clinic. With 200,000 new cases of breast cancer every year, “it was just untenable to be able to get the amount of drug that was needed.”

Coinciding with rising environmental concerns over deforestation, the taxol boom set the stage for a showdown: on the one side were patients and their families clamoring for a lifesaving drug; on the other side, environmentalists seeking to protect the forest. The controversy reached its climax in 1991, when the national news media caught wind of the story: “Save a Life, Kill a Tree?” asked an editorial in the New York Times.

Patient advocates argued it was unethical to value trees more than people. Environmentalists countered it was shortsighted to bulldoze a national treasure to harvest a chemical whose source would be depleted in a matter of years. For researchers involved with the project, the message was clear: find a solution to the supply problem or watch a promising new drug go up in smoke.