WITCHES’ BREW

Arthur Barclay stood at the foot of a large evergreen tree in a Washington State forest near the base of Mount St. Helens. The year was 1962. A botanist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Barclay was collecting plant samples as part of a new scientific research program sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). A few years earlier, researchers in Canada had made the accidental discovery that a chemical isolated from the Madagascar periwinkle plant could kill leukemia cells. Inspired by this surprising find, the NCI shifted its focus from synthetic products—the manmade chemicals they had pored over for nearly 20 years—to natural ones, specifically ones from plants.

As part of this plant program, Barclay sliced off a few stems, some needles, and a slab of bark from the tree, then dropped them in his burlap bag. He shipped the samples to a lab in Maryland, where they were screened for cancer-fighting potential.

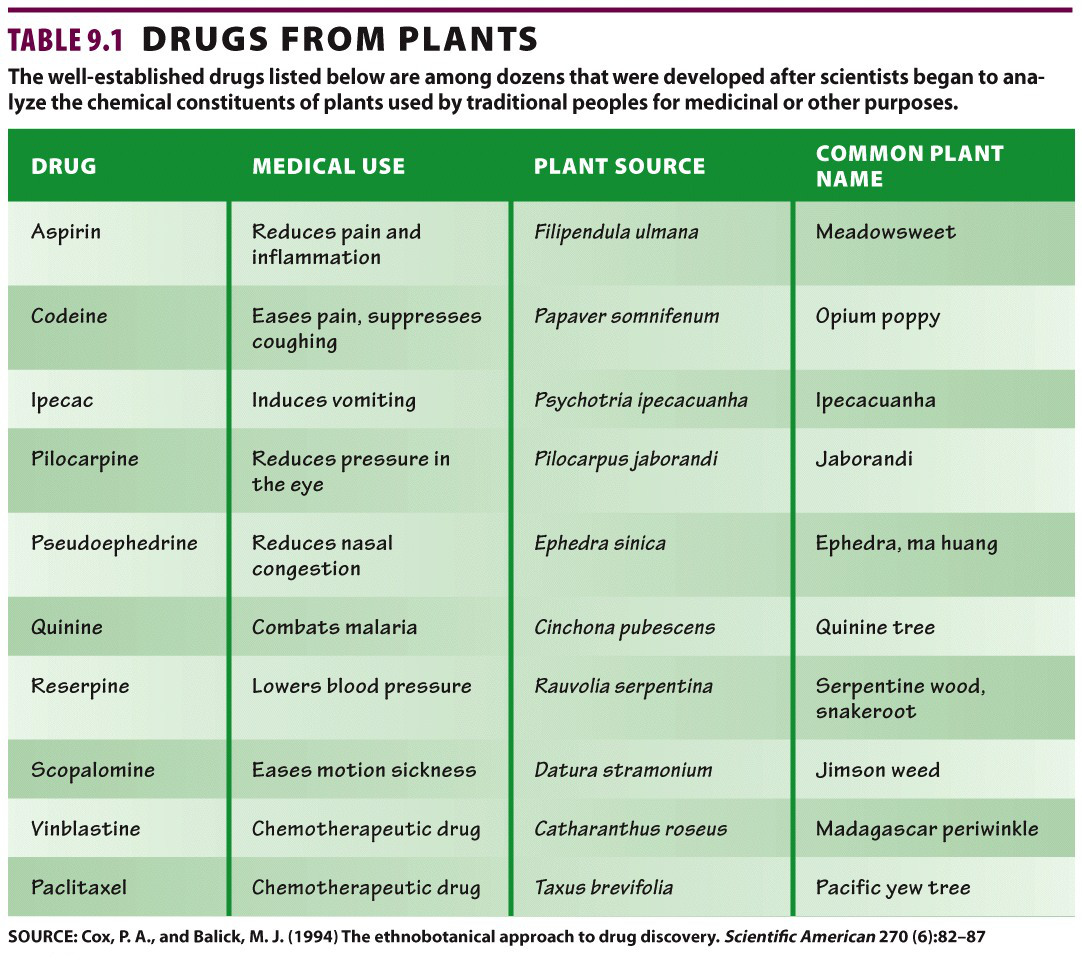

Plants have long been known to be rich sources of medicinal products. Traditional healers and practitioners of folk medicine have relied on plants to treat illnesses for millennia. And many of the medicines and drugs we use today, including morphine, cocaine, nicotine, and aspirin, come from plants (TABLE 9.1) . But at the beginning of the 1960s, nothing at all was known about plants that might be useful in fighting cancer. To find a therapeutic needle in the plant haystack, in 1960 the NCI created a screening program to test plant compounds for their potential as chemotherapeutic drugs. Between 1960 and 1981, NCI-affiliated scientists screened more than 100,000 plant extracts.

The overwhelming majority of these chemicals proved to be worthless as drugs. In fact, only a minuscule fraction ever received even so much as a second look. But in a few cases, the effort paid off.

In August 1962, just 2 years into the plant-screening program, the NCI received Barclay’s shipment of stems, needles, and bark. As they did with all such specimens, NCI scientists ground up the materials into an extract, which they squirted on cancer cells growing in a dish. Extract from the stems and needles had no effect. But the bark, on the other hand, had a powerful one: it killed the cancer cells.

Taxus brevifolia, the Pacific yew, is one species of a family of related evergreen trees. It grows very slowly and is found only in the forests of Washington, Oregon, and western Canada. The tree was considered a trash tree by the timber industry, which was more interested in Douglas fir. But people have long found uses for the yew, which has strong but pliant wood. And the reddish-barked tree has a rich history in folklore and literature, most likely because it is poisonous. (In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the witches add to their noxious brew “slips of yew, silvered in the moon’s eclipse.”) When extracts from the bark of Taxus brevifolia also turned out to kill cancer cells, it was not surprising that the tree caught the attention of scientists.

For researchers involved with the project, the message was clear: find a solution to the supply problem or watch a promising new drug go up in smoke.

Two people who took particular notice were Monroe Wall and Mansukh Wani, chemists at the Research Triangle Institute in North Carolina, who spent nearly 10 years, and a mountain of bark, working to identify the specific chemical responsible for Taxus brevifolia’s exciting effects. Finally, in 1971, they succeeded, and gave the substance a name: taxol.