THE POLITICS OF SUPPLY AND DEMAND

Once taxol’s mechanism was understood, the race was on to evaluate its clinical efficacy. Initially, researchers hoped the transition from lab bench to clinic would be straightforward. They soon made a depressing discovery: taxol is unusually hydrophobic and virtually insoluble in water, making it difficult to administer intravenously. Without some way to administer taxol to patients, it would be useless as a chemotherapy drug. At this point, many researchers were ready to abandon taxol altogether, but eventually scientists found a substance in which taxol could dissolve, and by 1984 the drug was ready for clinical testing.

Taxol progressed rapidly through clinical trials, quickly earning a name for itself as a promising new drug for the treatment of advanced ovarian and breast cancer. Taxol is “the most important new drug we have had in cancer for 15 years,” Samuel Broder, director of the NCI, told the New York Times. “I’m not saying it’s a cure, but I will tell you there are women who failed every other treatment who responded.”

Yet as effective as taxol was, researchers still had a huge problem on their hands: making enough of the drug for all the patients who needed it. In 1990, just to cover the clinical trials then under way, the NCI estimated that it would need 130 kg of taxol, requiring 1,500,000 pounds of bark.

Making matters worse, researchers soon found themselves facing another hurdle: bad publicity. When, in 1987, the NCI placed an order with the USDA for 60,000 pounds of bark, it caught the attention of environmentalists—as did an even larger order, in 1991, for 750,000 pounds. Concerned that the forest was being quietly shredded, activists protested the government’s plans. Working with the Environmental Defense Fund, they launched a series of petitions, with the result that, over the next few years, the NCI found itself increasingly caught up in a fierce battle with an unlikely opponent: the northern spotted owl.

This rare bird made its home in tree nooks in forests where the Pacific yew grew, and environmentalists had for years been arguing that clear-cutting was threatening the birds’ habitat. Harvesting of yews for taxol, they claimed, would only exacerbate this problem. Activists lobbied successfully to get the owl classified as a threatened species under the 1963 Endangered Species Act. The owl was just one forest inhabitant, but it became the face of the environmental movement’s opposition to deforestation.

Although the number of trees required to obtain taxol paled in comparison to the number of Taxus trees that were routinely slashed and burned during normal logging operations, the media presented the controversy as a stark battle between environmentalists and cancer patients—aided in part by the participants themselves: “I love the spotted owl, but I love people more,” wrote Bruce Chabner, Chief of the Division of Cancer Treatment at the NCI, in a 1991 Wall Street Journal article.

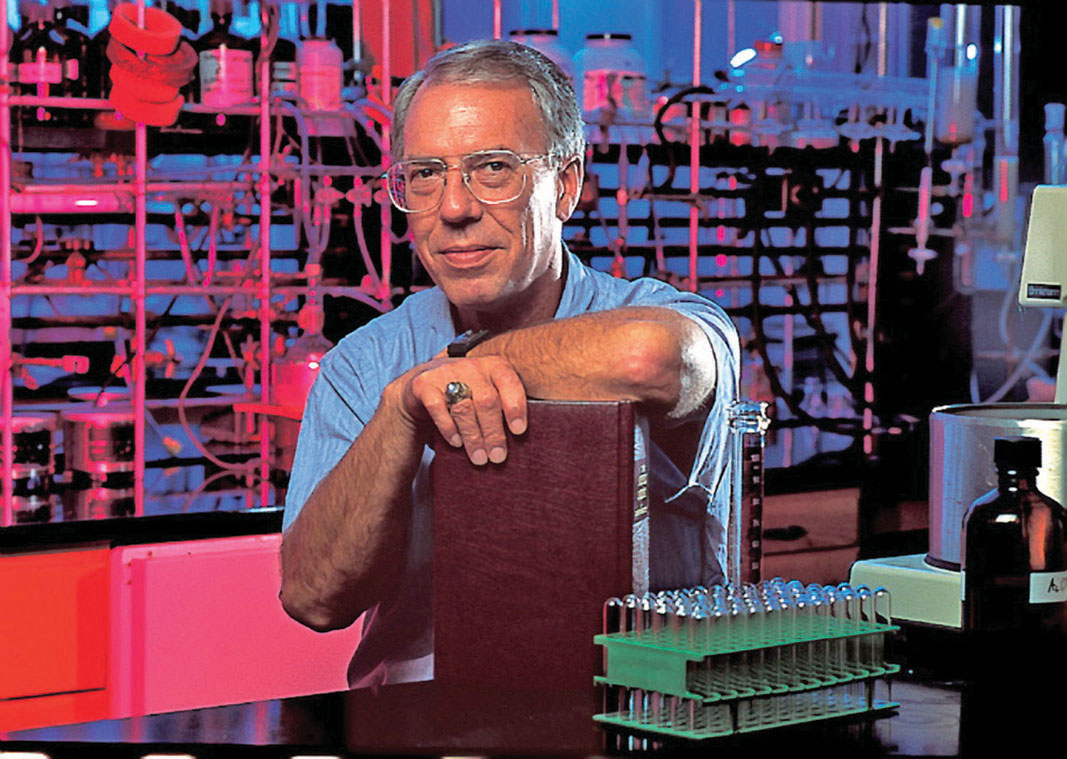

With a political firestorm complicating the already difficult supply problem, scientists at the NCI realized they would need to find an alternative source of the chemical if it was ever to see the light of day as a drug. The director of the NCI’s plant program promptly got on the phone with chemists around the country, urging them to find a solution. Robert Holton, a chemist at the University of Florida, remembers the conversation vividly: “He basically told me it was time I got off my butt and did something,” Holton later told the journal Research in Review. Eighteen months later, Holton delivered the goods. Using a method known as semisynthesis, he isolated the complicated portion of the taxol molecule from needles from the English yew, which is much more common than the Pacific yew. Then he attached the more easily synthesized unique “tail” that gives taxol its distinctive identity.

It was a huge breakthrough. If Holton’s method could be developed for use on an industrial scale, then Taxus trees would no longer have to be killed, and the spotted owl would be spared as well.

With much of the intellectual work done, and straining under the cost of its by then substantial investment of $32 million, the NCI decided that it was time to turn the project over to a pharmaceutical company equipped to make and sell the drug. (The NCI doesn’t market drugs.) The lucky winner of the contract was New Jersey-based Bristol Myers, which acquired rights to taxol in 1991.

In just 2 years, Bristol was able to use Holton’s method to bring a plentiful supply of the drug to market. Because much of the clinical research and development had already been completed, the process of getting Food and Drug Administration approval for the drug was speedy. Taxol was approved for the treatment of ovarian cancer in 1992 and for breast cancer in 1994.

What should have been heralded as a therapeutic triumph, however, quickly turned sour when it was discovered that Bristol was charging more than 20 times what it cost the company to produce the drug. Critics of the pharmaceutical company argued that, as a result of its expensive price tag, many of the taxpayers whose money had funded the research and development of the drug would be unable to afford it, while everyone else would effectively be paying for it twice. Bristol countered that its fee for the drug was justified given the size of its investment–$1 billion. Nonetheless, in 1993, the drug’s first year on the market, congressional hearings were held to determine whether Bristol’s actions were legal. No wrongdoing was found and the matter was ultimately dropped.

Bristol’s decision to trademark the chemical name “taxol” also proved controversial. Normally, when a drug goes to market, it gets a new trade name (acetaminophen, for example, became Tylenol). Bristol chose not to create a new trade name, which meant that scientists had to come up with a new generic name for a chemical that had been known as taxol for nearly 30 years. Thus taxol became Taxol®, and the generic name became paclitaxel.

Nevertheless, the company had done what it was supposed to do–solve the supply problems and bring the drug to market. “Bristol did a terrific job in getting the drug to patients,” says Horwitz.