FROM HERESY TO ORTHODOXY

As soon as her 1967 paper was published, criticism rolled in. Many of Margulis’s colleagues were skeptical, even dismissive, citing a lack of supporting evidence. Most of the evidence that Margulis marshaled in support of her hypothesis was circumstantial rather than direct (the conclusive DNA evidence did not come until 1978). There was philosophical opposition, too. To many people, bacteria were “bad” because they were known to cause disease; the idea that we have bacteria to thank for our very existence was difficult for many to accept. Then, too, the notion of endosymbiosis seemed to go against evolutionary dogma, which held that evolution occurred in small steps as a result of an individualistic “struggle for existence.” Endosymbiosis was not a small step, it was a huge one. And it wasn’t about competition as much as cooperation. For these reasons, it just didn’t sit well with many hard-nosed Darwinists.

For her part, Margulis never shrank from her position or gave up pushing her case. In fact, the resistance she encountered seemed almost to embolden her, and she spent years uncovering many other examples of symbiotic relationships at work in nature.

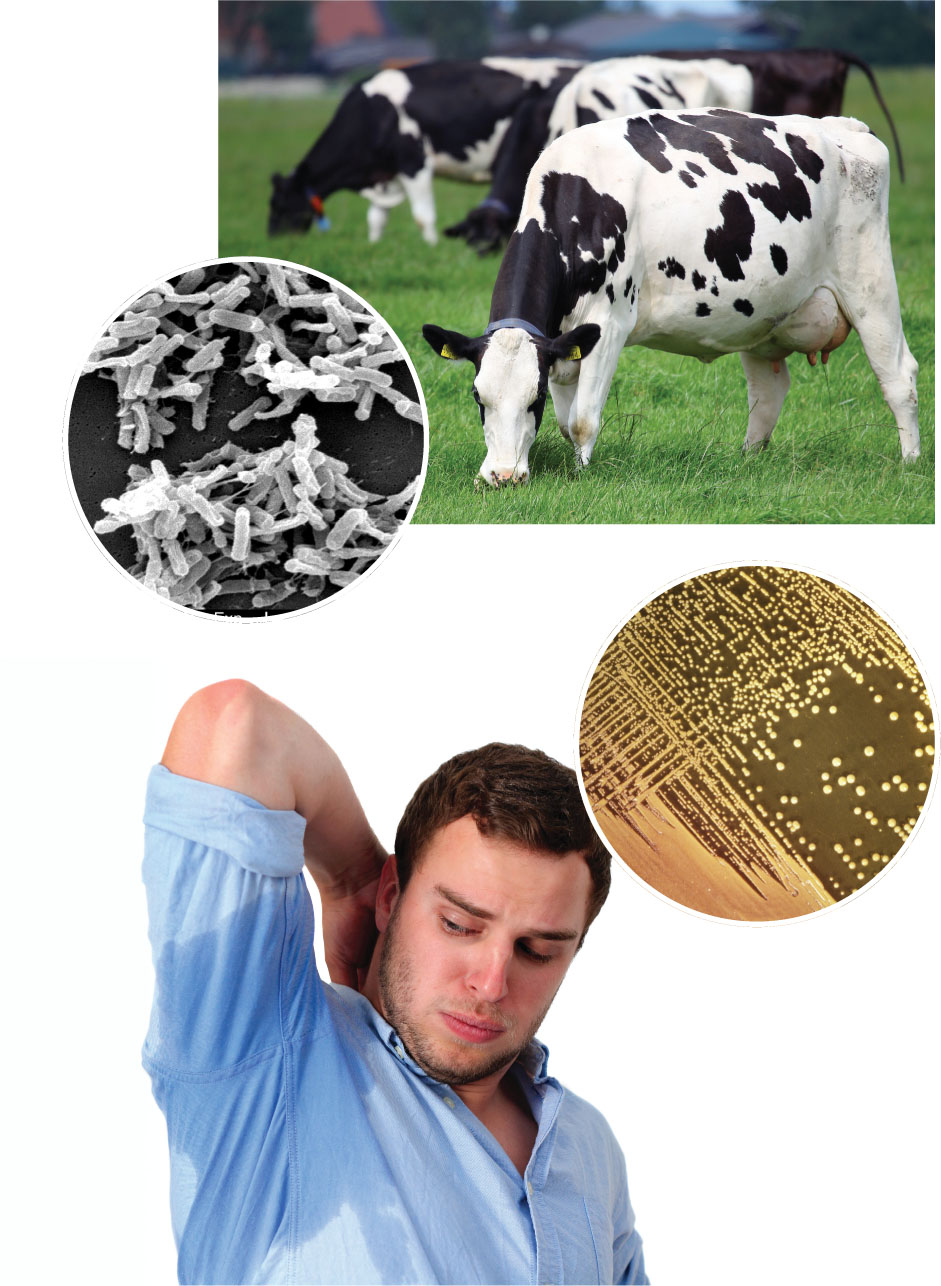

“Look at a cow,” she said in a 2011 interview with Discover magazine. “It is a 40-gallon fermentation tank on four legs. It cannot digest grass and needs a whole mess of symbiotic organisms in its overgrown esophagus to digest it.”

Or look at your own body. “There are hundreds of ways your body wouldn’t work without bacteria. Between your toes is a jungle; under your arms is a jungle. There are bacteria in your mouth, lots of spirochetes, and other bacteria in your intestines. We take for granted their influence. Bacteria are our ancestors.”

Much current research is focused on understanding our human microbiome–the population of bacteria that lives on and in our bodies and influences many aspects of our health. In addition to helping us digest food and shaping our immune system, our unique microbiome may even influence our susceptibility to conditions such as diabetes and obesity. The idea that these bacteria are not passive freeloaders but crucial constituents of our bodies is a relatively new way of looking at things–but it would hardly have come as a surprise to Margulis.

When Margulis died in 2011 at the age of 73, she was remembered as the person who most fundamentally changed our view of cells. These days, the idea that mitochondria and chloroplasts started as free-living organisms is accepted nearly as fact by the scientific mainstream, and we now refer to the theory of endosymbiosis, acknowledging the abundant evidence and wide support it has.

“The evolution of the eukaryotic cells was the single most important event in the history of the organic world,” said Ernst Mayr, the grandfather of modern evolutionary studies, who died in 2005 at the age of 100. “Margulis’s contribution to our understanding the symbiotic factors was of enormous importance.” Richard Dawkins, the British don of evolutionary biology, described the theory of endosymbiosis as “one of the great achievements of twentieth-century evolutionary biology.” Botanist Peter Raven said the idea caused “nothing less than a revolution” in our thinking about the cell.

Not all of Margulis’s ideas have gained wide support. In particular, her claim that the whiplike tail of a sperm cell derives from a formerly free-living bacterium called a spirochete is not accepted by the scientific establishment. Nor is her idea, put forward in recent years, that AIDS is caused not by a virus but by a cellular parasite, the same one that causes syphilis.

But on one of the most important questions of modern biology, her intellectual daring paid off. Asked by the Discover interviewer how she felt about being the source of so many controversial ideas over the years, Margulis responded in typical fashion: “I don’t consider my ideas controversial. I consider them right.”

MORE TO EXPLORE

Sagan, L. (1967) On the origin of mitosing cells. Journal of Theoretical Biology 14:225–274.

Sagan, L. (1967) On the origin of mitosing cells. Journal of Theoretical Biology 14:225–274.

Margulis, L., and Sagan, D. (1986) Microcosmos: Four Billion Years of Evolution from Our Microbial Ancestors. New York: Summit Books.

Margulis, L., and Sagan, D. (1986) Microcosmos: Four Billion Years of Evolution from Our Microbial Ancestors. New York: Summit Books.

Teresi, D. (2011) Interview with Lynn Margulis. Discover. http://discovermagazine.com/2011/apr/16

Teresi, D. (2011) Interview with Lynn Margulis. Discover. http://discovermagazine.com/2011/apr/16

Margulis, L. (2006) Microbial planet. Interview with Astrobiology Magazine,Part 1. http://www.astrobio.net/interview/2100/microbial-planet

Margulis, L. (2006) Microbial planet. Interview with Astrobiology Magazine,Part 1. http://www.astrobio.net/interview/2100/microbial-planet

Sapp, J. (2012) “Too Fantastic for Polite Society: A Brief History of Symbiosis Theory.” In Lynn Margulis: The Life and Legacy of a Scientific Rebel, edited by Dorian Sagan. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Sapp, J. (2012) “Too Fantastic for Polite Society: A Brief History of Symbiosis Theory.” In Lynn Margulis: The Life and Legacy of a Scientific Rebel, edited by Dorian Sagan. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.