Journey to an Idea

Though Darwin is the most famous of the figures associated with the theory of evolution, he did not invent the idea. Nor was he alone among his contemporaries in studying it. In fact, the notion that species change gradually over time had been around for generations. To be sure, most people in the 1830s—Darwin included—still assumed that species were fixed and unchanging, created perfectly by God. But evidence to the contrary had been accumulating for some time. Explorers and naturalists were traveling to faraway lands, and finding unusual plants and animals they had never seen before. Fossils were being uncovered, providing evidence that some species no longer seen on Earth had lived in the past. And anatomists were noting uncanny physical resemblances between different species, including chimpanzees and humans. Evolution was in the air when Darwin began thinking about it.

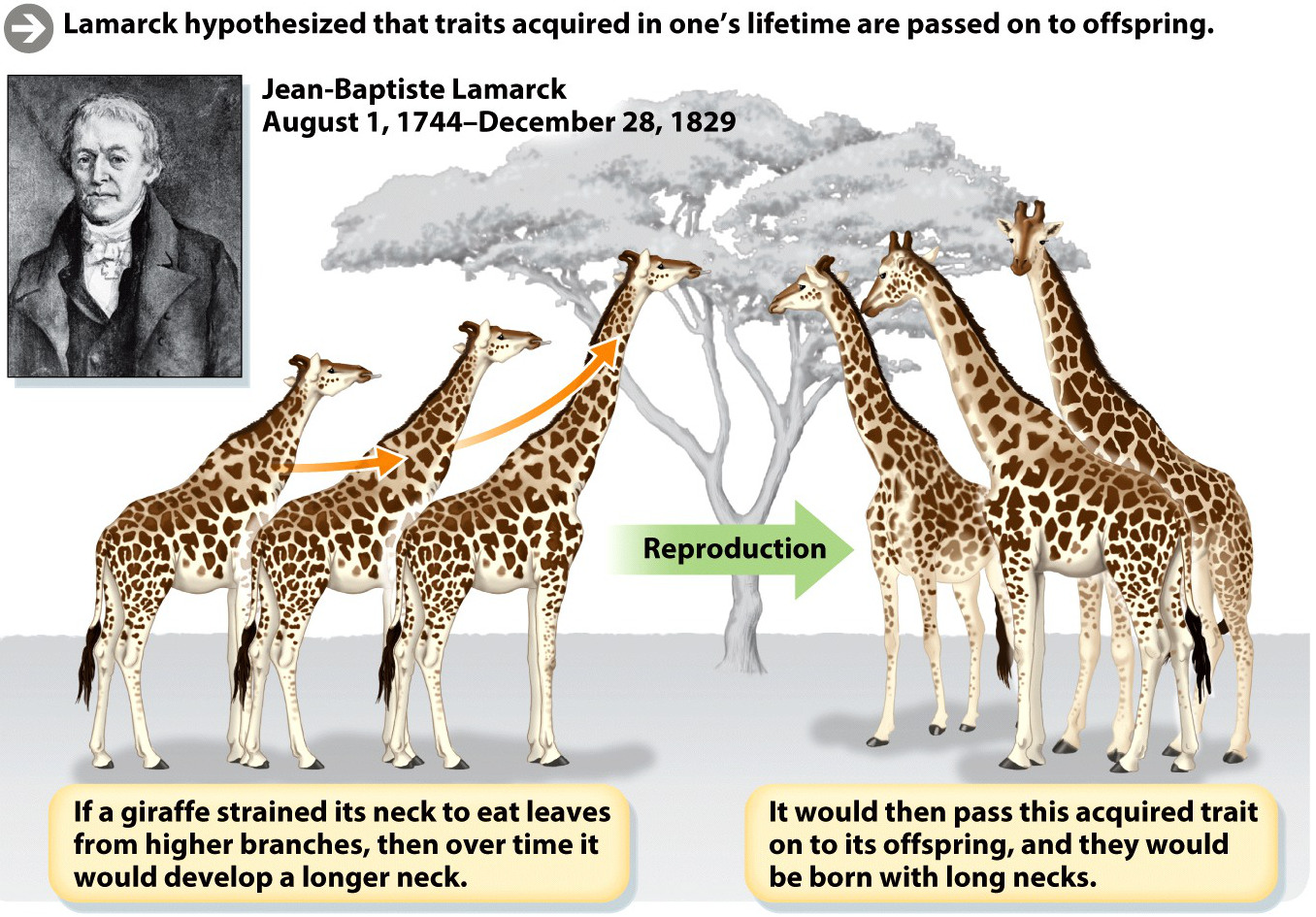

However, the ideas that people in Darwin’s time had proposed to explain how species changed were flawed. One common misconception was Lamarckianism, named after the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who suggested that species could change through the inheritance of acquired characteristics. In the Lamarckian view, giraffes, for example, developed their long necks by continually stretching them to feed on tall trees. Once it acquired its long neck, a giraffe could then pass that advantageous trait on to its offspring. This idea of the inheritance of acquired characteristics, while incorrect, was a popular one in Darwin’s time—one that even Darwin himself found it hard to fully shake off in his writings (INFOGRAPHIC M5.1).

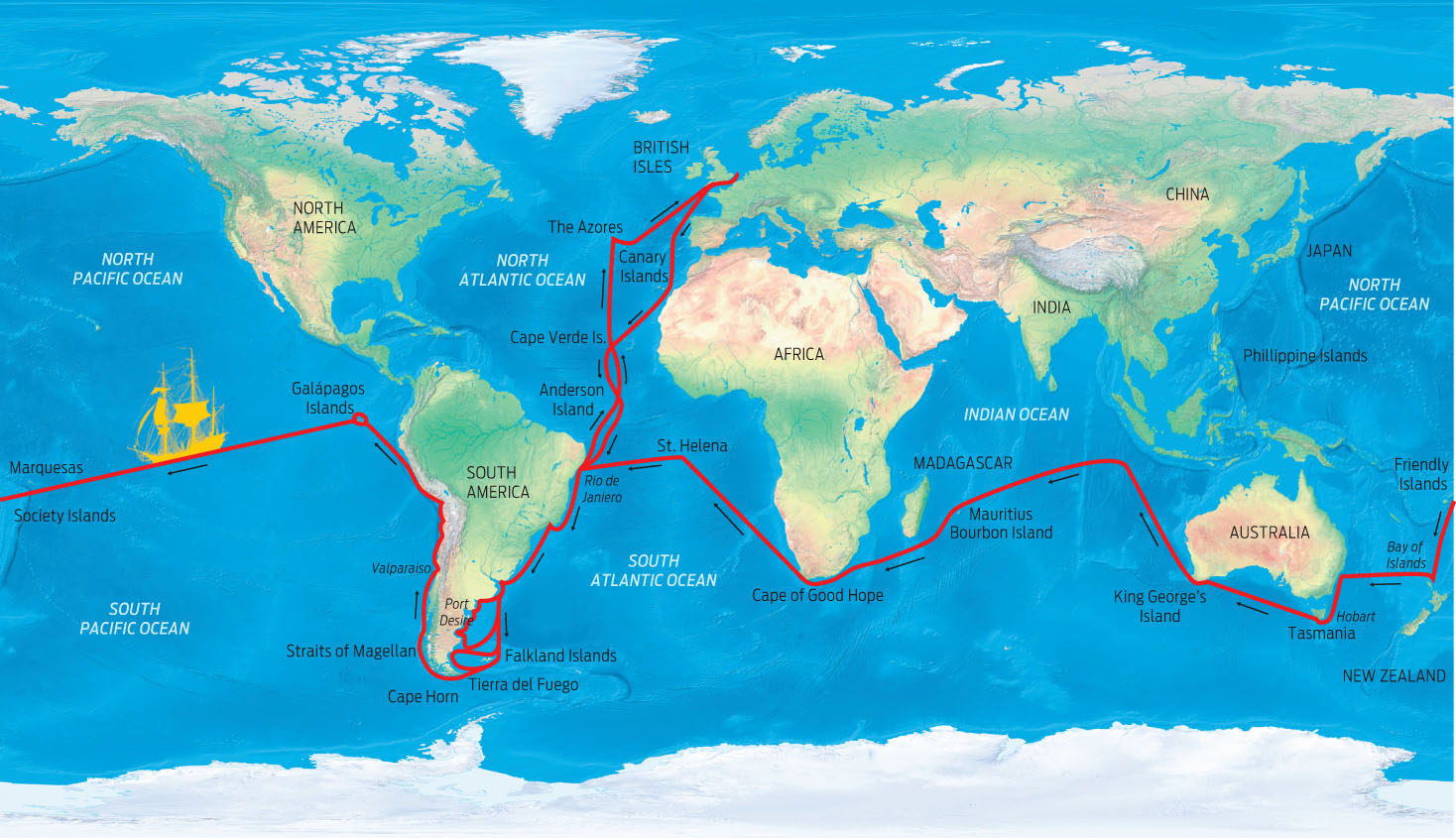

Though it would be years before Darwin proposed his own theory of evolution, his trip around the world provided him with an indispensable foundation. He kept a diary of his adventures, which was later published as The Voyage of the Beagle (1839).

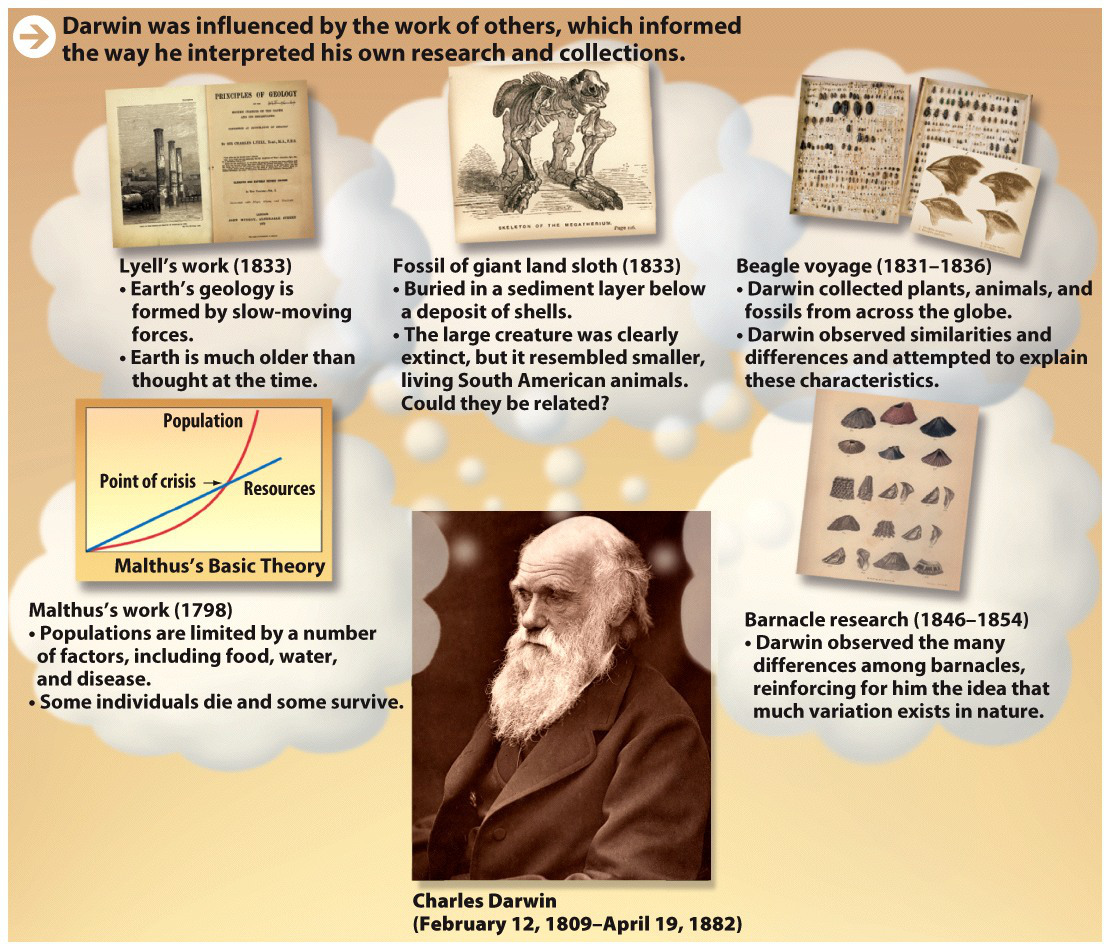

While at sea, Darwin had plenty of time to read and think about the ideas then being discussed in scientific circles. He read, for instance, the work of Charles Lyell whose Principles of Geology (1830–1833) argued that Earth was much older than the 6,000 years popularly accepted at the time (a figure based on a literal reading of the Bible), and that its geology had been shaped entirely by incremental forces operating over a vast expanse of time. Valleys, for example, were formed by the slow grinding forces of wind and water, not by catastrophic floods; mountains were pushed up gradually by the action of volcanoes and earthquakes. Lyell’s view of incremental change producing dramatic results over great spans of time left an indelible impression on Darwin.

The world has been different ever since Darwin.

The world has been different ever since Darwin.

—STEPHEN JAY GOULD

Not long into his trip, he saw something that seemed to confirm Lyell’s view. While docked at the Cape Verde islands, 300 miles off the west coast of Africa, he noticed a white layer of compressed seashells and corals embedded in a rock face 30 feet above sea level. This layer had clearly been formed in the sea, but had somehow been lifted up out of the water. Later on his trip, Darwin witnessed how this might happen: after an earthquake devastated the town of Concepción, Chile, he noticed that the coastline had been pushed up several feet, as shown by the rim of mollusks and barnacles that hovered out of the water around the bay. Lyell was right.

With such thoughts of an ancient, slowly changing Earth on his mind, Darwin studied the plants, animals, and geology at each stop on his trip, collecting fossils and specimens of local flora and fauna wherever he went (INFOGRAPHIC M5.2).

While exploring the shore of Argentina in August 1833, Darwin unearthed a particularly prized find: the fossilized remains of several large mammals embedded in a sea cliff, including one that looked like a giant armadillo and another that resembled a giant sloth. These animals had clearly lived long ago and were now extinct, since such oversize mammals no longer roamed the plains of Argentina. And yet the ancient creatures bore a striking resemblance to the much smaller armadillos and sloths that were indigenous to the area. Why should animals separated by such vast epochs of time share such similar anatomical structures? To Darwin, this suggested that these creatures were ancestrally related to one another, and also that the species had changed gradually over time. Darwin was beginning to question the conventional wisdom of his day.

In 1835, the young naturalist stepped ashore on the Galápagos Islands, off the coast of Ecuador. On this archipelago, Darwin observed and collected many creatures, among them a variety of small birds. Months later, while studying the specimens back in England, he learned that they were all species of finch. Each species was distinguishable by a different size and shape of beak, but they all bore a family resemblance. He later wrote in The Voyage of the Beagle, “One might really fancy that, from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.”

This notion of one species giving rise over time to new species Darwin came to call “descent with modification,” which he represented in his notebooks by a diagram that looked like a branching tree. (Darwin himself didn’t like using the term “evolution” because he thought it gave a mistaken idea of progress or direction toward a goal, but “evolution” is the term that stuck.)

After 5 years traveling the globe, Darwin returned home to England in October 1836, but his intellectual journey was only just beginning. He began to think more seriously about how species might change over time. A key insight came to him in September 1838 while reading the work of the political economist Thomas Malthus, whose pessimistic book An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) described how hunger, starvation, and disease would ultimately limit human population growth. The same must be true of plant and animal species, Darwin realized. If every individual in a population reproduced, even in a slowly reproducing population such as elephants, the world would be completely overrun with elephants in not that many generations. Since Earth is not overrun with elephants, factors must be limiting their population growth. Such limitations, Darwin reasoned, would lead to competition for resources that would put weaker individuals at a disadvantage. “It at once struck me,” Darwin later wrote in his autobiography “that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species.”

These favorable variations needn’t be very pronounced, he realized. All that was needed was for certain individuals to have a slight edge over others in the competition to survive and reproduce. These helpful variations would then be inherited by offspring and become more common in the population. In effect, the environment was “selecting” for favorable traits, much as plant and animal breeders selected and perpetuated desirable varietals—a plant with especially large fruit, for instance, or the many breeds of dogs we see today.

This idea of “natural selection” was Darwin’s original contribution to the theory of evolution. Others had speculated at length about species change—most notably Robert Chambers in Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844)—but Darwin was the first to provide a clear mechanism of evolution. The philosopher of science Daniel Dennett has called natural selection “the single best idea anyone has ever had.”

Among other things, natural selection provided a powerful explanation for the apparent design seen in nature. Before Darwin, the conventional view was that provided by William Paley, whose book Natural Theology (1802) Darwin had read in college. In that work, Paley made his famous “argument from design”: that is, many creatures are so finely constructed and well adapted to their environment that their existence implies the existence of a designer—much in the way that the existence of a watch implies the existence of a watchmaker. To many people in the 19th century, that designer was God. With the idea of natural selection, Darwin did away with the need for a watchmaker: natural selection could accomplish the same thing without any input from a designer.

It at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species.

It at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species.

—CHARLES DARWIN

By 1844, Darwin had developed his ideas into a 200-page manuscript that he hoped would be the definitive word on the subject. He did not rush his ideas about natural selection into print, however. He knew that his ideas would be controversial, contradicting as they did strongly held beliefs about God and the special creation of all animals, including humans. Other scientists with evolutionary ideas were causing quite a stir in England and being openly ridiculed (for this reason Robert Chambers had published his book anonymously). Even sharing his theory of evolution by natural selection with trusted colleagues, Darwin said, was “like confessing a murder.” To withstand challenges, he knew he would need more detailed evidence.

And so, at age 37, Darwin began to investigate closely one large group of animals: barnacles, the small invertebrates that cling to ships or marine life. Darwin spent 8 years, from 1846 to 1854, carefully cataloguing the barnacles’ tiny features, comparing and contrasting them with those of other known invertebrates. It was tedious work, leading Darwin to write, “I hate a Barnacle as no man ever did before.” Yet the work proved valuable: it reinforced his idea that a great deal of variation exists in nature—barnacles are nothing if not diverse—and it provided ample evidence of descent with modification since the creatures clearly shared adaptations with other invertebrates (INFOGRAPHIC M5.3).

In the summer of 1858, Darwin was hard at work on his “species” book when he received a letter from a young naturalist with whom he had a casual acquaintance, a collector named Alfred Russel Wallace who made a living selling rare butterflies and birds to other collectors and museums. The envelope was postmarked from an island in Indonesia. Inside was a 20-page manuscript describing the author’s bold new idea about how species change over time, which he wanted Darwin to read and have published. Darwin, it seemed, had been scooped.