In Darwin’s Shadow

Although we often credit Darwin with the discovery of natural selection, he was not alone in charting this intellectual territory. Another British naturalist was also hot on the trail. Like Darwin, Wallace was fascinated by natural history and had a thirst for adventure. In other ways, though, the two men couldn’t have been more different. Darwin came from a wealthy family and had received a prestigious Cambridge education. He was greeted as a minor celebrity when he returned from his trip around the world and was accepted into the scientific establishment. Wallace, on the other hand, was a man of more humble origins, for whom nothing in life had come easily.

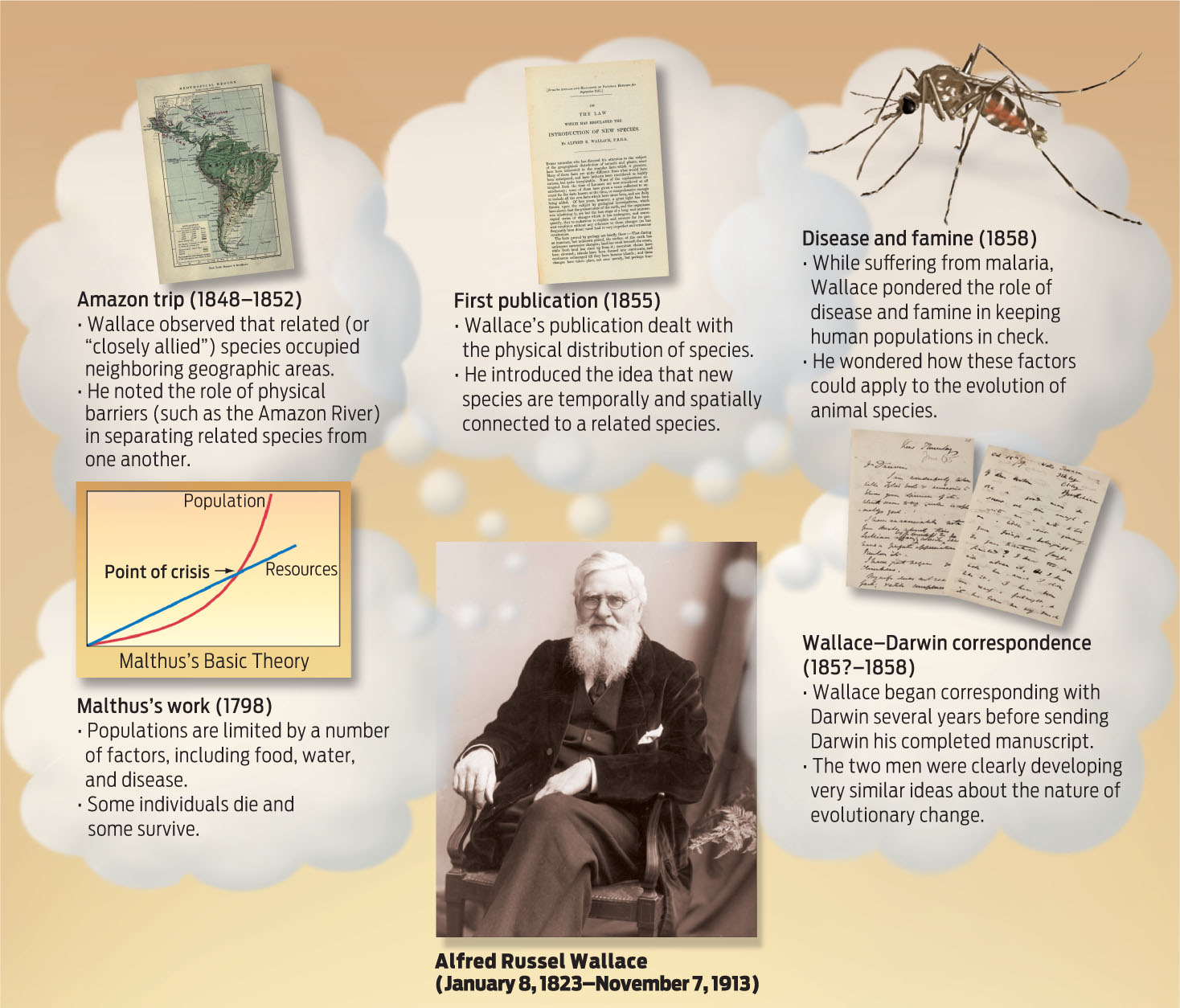

The eighth of nine children, Wallace could not afford a university education. He attended night school and supported himself as a builder and railroad surveyor. His budding fascination with natural history, though, led him to read widely. Like Darwin, he read Lyell’s work on geology, Malthus’s work on human population, and Chambers’s Vestiges. And, of course, he devoured Darwin’s travel account, The Voyage of the Beagle.

In 1848, having scrimped and saved, the 25-year-old Wallace set sail for Brazil, to the mouth of the Amazon River. There he hoped to earn his reputation as a respectable scientist by understanding the origin of species. Exploring the rain forest of the Amazon, Wallace was struck by the distribution of distinct yet similar-looking (what he called “closely allied”) species, which were often separated by a geographic barrier such as a canyon or river. For example, he noted that different species of sloth monkey were found on different banks of the Amazon River. Over the course of his 4-year trip, Wallace scoured the Amazon and collected thousands of specimens.

Wallace was on his way home to London with his specimens in 1852 when disaster struck: his ship caught fire and sank. Wallace survived, but he lost everything—his notes, sketches, journals, and all his specimens. In spite of this catastrophe, Wallace was undeterred. Less than 2 years later, he was off on another collecting expedition, this time to the Malay archipelago (what is now Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia).

Wallace’s first paper, “On the Law Which Has Regulated the Introduction of New Species,” was published in September 1855. Based on his island work, it focused on the similar geographical distribution of “closely allied” species. For example, “the Galápagos Islands,” he wrote “contain little groups of plants and animals peculiar to themselves, but most nearly allied to those of South America.” From these observations, Wallace deduced this law, as he called it: “Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a pre-existing closely allied species.”

Wallace’s article was groundbreaking, foreshadowing Darwin in a number of ways, but it lacked an explanation—a mechanism—of exactly how one species might have evolved from another.

Wallace continued his travels, but in early 1858 disaster struck again: he contracted malaria. Confined to bed, he let his mind wander. He thought about what Malthus had written about disease and how it kept human populations in check. How might these forces of disease and death, multiplied over time, influence animal populations, he wondered? Then came the flash of insight—like “friction upon the specially-prepared match,” he recalled: in every generation, weaker individuals will die while those with the fittest variations will survive and reproduce; as a result species will change and adapt to their surroundings, eventually forming new species. Wallace had worked out the mechanism for evolution that was missing from his earlier work. He quickly wrote out his idea and sent it to the one naturalist he thought might be able to appreciate it. This was the 20-page manuscript that arrived on Darwin’s doorstep on June 18, 1858 (INFOGRAPHIC M5.4).

Darwin was stunned. For 20 years he had been working diligently on the same idea and now it seemed someone else might get credit for it. “All my originality will be smashed,” he wailed to his friend Lyell. Recognizing Darwin’s predicament, Lyell and other colleagues devised a plan that would clearly establish Darwin’s intellectual precedence: they would arrange to have papers by both men presented at a meeting of the Linnaean Society in London. The meeting took place on July 1, 1858. The papers were dutifully read, but there was no discussion or fanfare. In fact, neither of the authors was even present: Wallace was still traveling in Malaysia and Darwin was mourning the recent death of his young son and too distraught to attend.

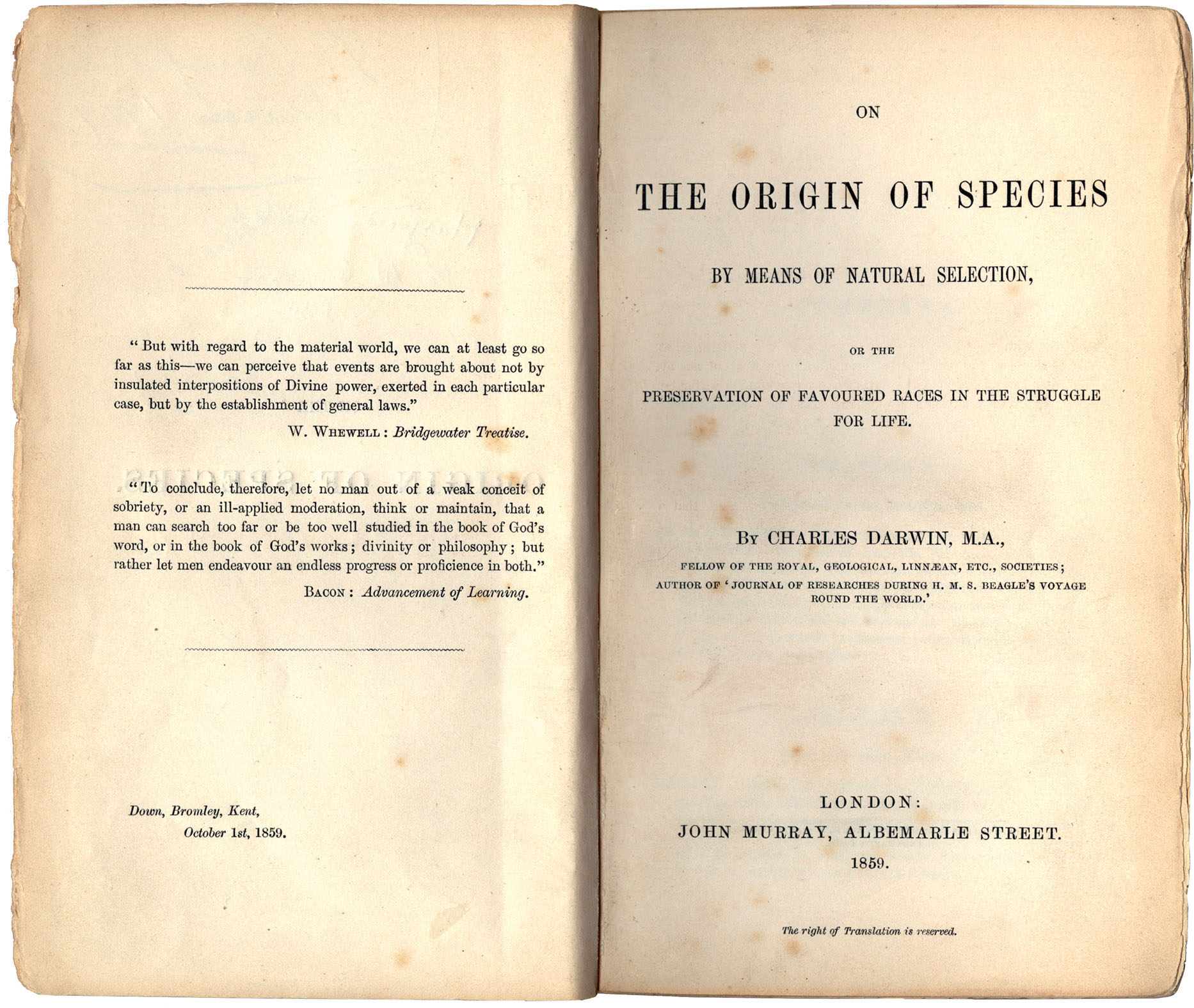

The scientific meeting secured Darwin’s reputation, but still he was unsettled. Wallace’s communication had lit a fire under his feet. He needed to finish his book. That work, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, was published in November 1859. It would become one of the most famous books of all time, going through six editions by 1872.

Although it may seem that Wallace was cheated of his rightful recognition as a discoverer of evolution by natural selection, he was never bitter. On the contrary, he was delighted when he heard about his copublication with Darwin. He fully accepted that Darwin had formulated a more complete theory of natural selection before he did, and there is no trace of resentment in his later writings. In fact, Wallace titled his major work Darwinism, in recognition of the other man’s intellectual influence.

After the presentation of 1858, Wallace stayed in the Malay archipelago for 4 more years, systematically recording its fauna and flora and securing his reputation as both the greatest living authority on the region and an expert on speciation. In fact, Wallace is responsible for our modern-day definition of “species.” In work on butterflies, he defined “species” as groups of individuals capable of interbreeding with other members of the group but not with individuals from outside the group. This idea—known today as the biological species concept—remains one of the most important in evolutionary theory.

MORE TO EXPLORE

Darwin, C. (1909 [1839]) The Voyage of the Beagle. New York: P. F. Collier and Son http://books.google.com/books?id=MDILAAAAIAAJ&q

Darwin, C. (1909 [1839]) The Voyage of the Beagle. New York: P. F. Collier and Son http://books.google.com/books?id=MDILAAAAIAAJ&q

Beagle Voyage, Natural History Museum http://is.gd/RRNl9T

Beagle Voyage, Natural History Museum http://is.gd/RRNl9T

Browne, J. (2008) Darwin’s Origin of Species. New York: Grove Press.

Browne, J. (2008) Darwin’s Origin of Species. New York: Grove Press. Wallace, A. R. (1869) The Malay Archipelago. London: Macmillan http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/w/wallace/alfred_russel/malay/

Wallace, A. R. (1869) The Malay Archipelago. London: Macmillan http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/w/wallace/alfred_russel/malay/

Secord, J. (2003) Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Secord, J. (2003) Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.