I WANT MY DDT

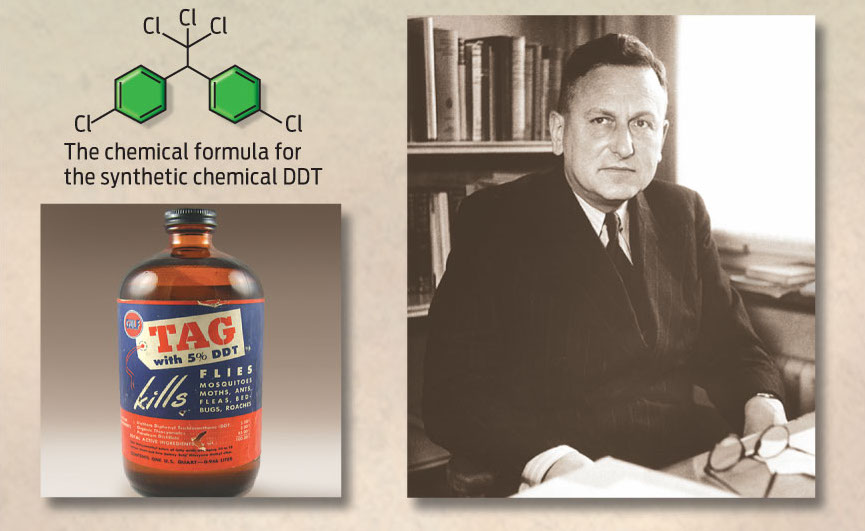

DDT, a synthetic chlorinated hydrocarbon, was discovered to be a potent insecticide in 1939 by the Swiss chemist Paul Müller. DDT poisons the nervous system of insects and other animals, and was first widely used during World War II to combat insect-carried diseases, such as typhus and malaria, among U.S. soldiers. (Typhus is carried by lice, which infested many soldiers living in cramped quarters; malaria is carried by mosquitoes, such as those that live in the islands of the South Pacific.) As a public health measure, DDT succeeded marvelously, saving countless lives during the war. For his work Müller was awarded a Nobel prize in 1948.

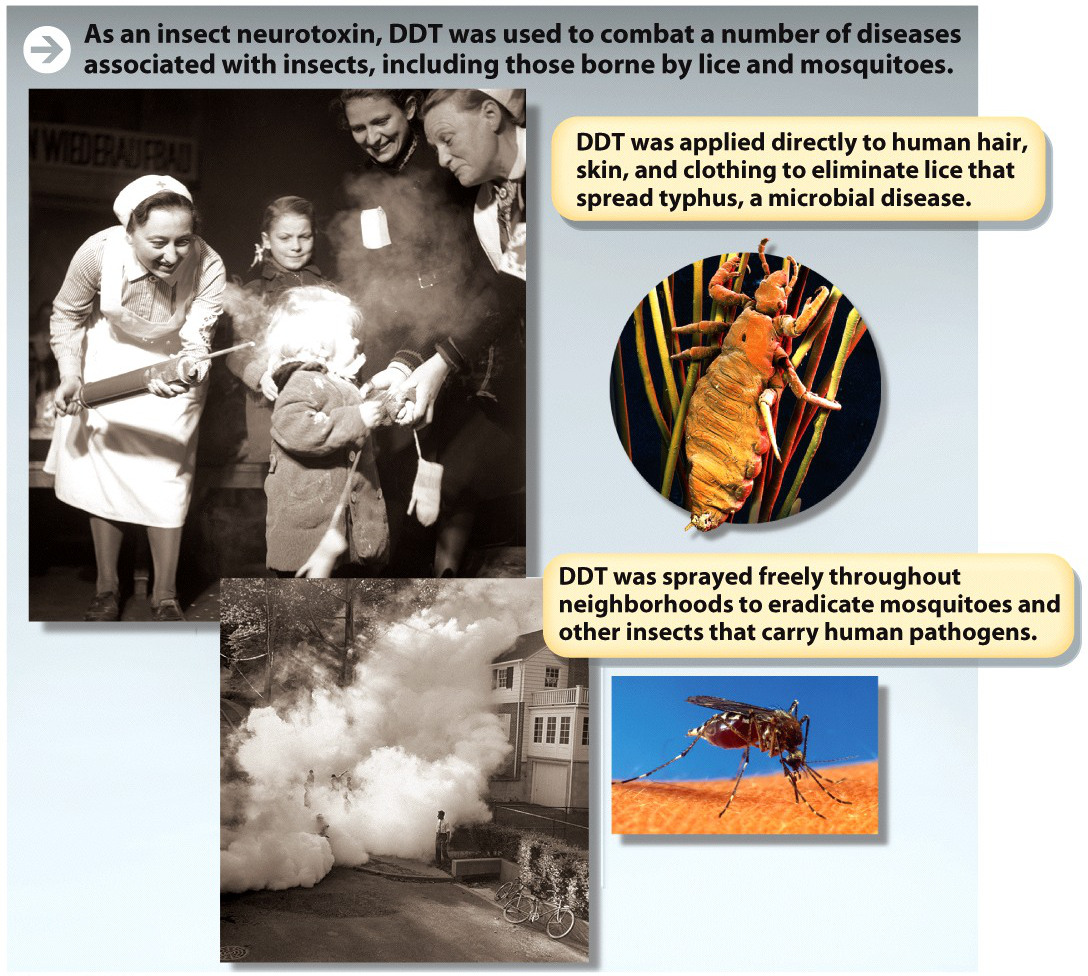

After the war, DDT became available to the public as a commercial pesticide and was widely used by farmers to protect their crops and by public health officials to contain insect-borne disease. The chemical companies that manufactured the potent bug-killer advertised it as an aid to domestic comfort and tranquility. Photos and newsreels from the era document mass spraying of suburban neighborhoods as children played happily in the chemical clouds (INFOGRAPHIC M6.1).

But by the late 1950s, a number of scientists and citizens had become concerned that indiscriminate spraying of pesticides like DDT was doing more harm than good. Efforts by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to eliminate gypsy moths and fire ants in a number of states had reportedly killed off more than just these target pests—scores of other insects, fish, and birds had also been wiped out. By 1958, when Carson received the letter from her friend, there were several court cases directed against the USDA in an effort to stop the indiscriminate spraying.

Carson began approaching scientists around the country, including many of her former colleagues in the Fish and Wildlife Service, for information about pesticide use and toxicity. “The more I learned about the use of pesticides, the more appalled I became,” she later said. Over the next 4 years, she interviewed more scientists, scoured the research literature, and culled through newspaper reports. The result was Silent Spring, a comprehensive treatise with 50 pages of footnotes.

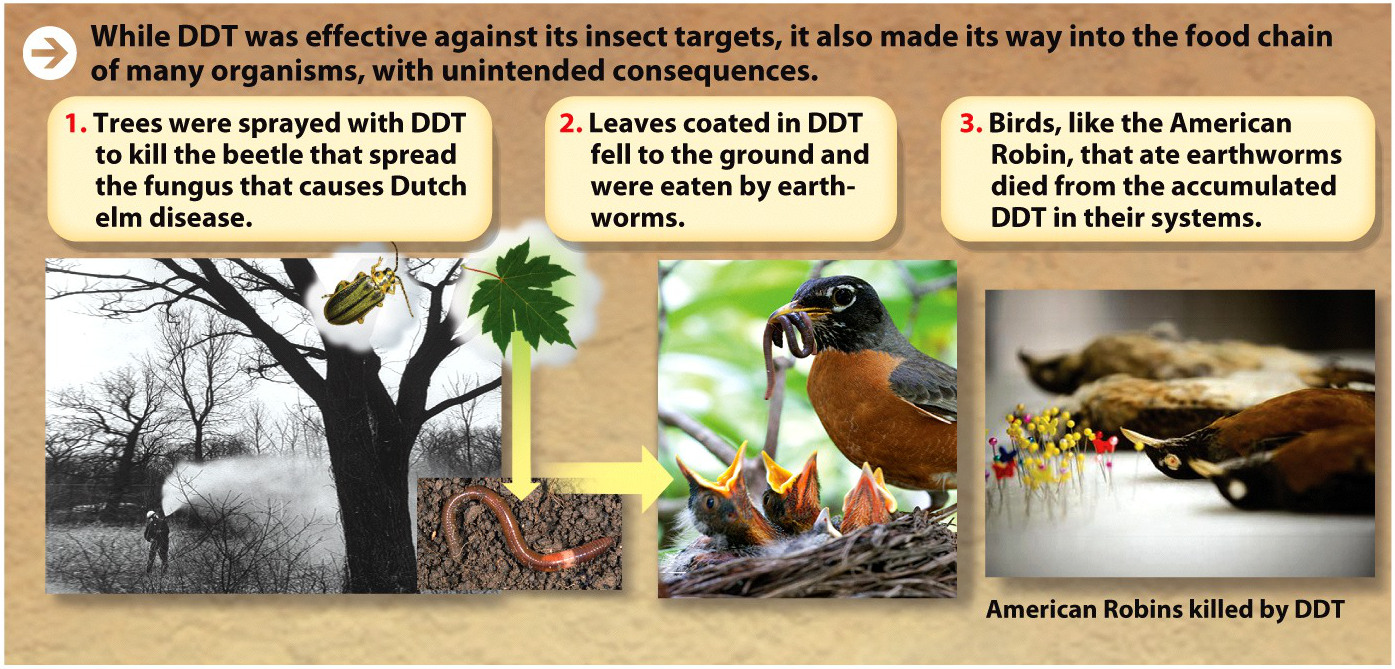

Carson’s book was filled with example after depressing example of the destruction that synthetic pesticides were wreaking on natural populations of animals, most famously birds. For example, in the mid-1950s, government officials in states across the Midwest attempted to deal with growing problem of Dutch elm disease, which was killing off the popular trees, by spraying the trees with DDT. Dutch elm disease is caused by a fungus, but it is spread from tree to tree by beetles that feed on the trees’ leaves. To combat the beetles, scientists sprayed the trees with DDT. In the autumn, leaves coated in DDT fell to the ground, where they were eaten and decomposed by earthworms, which took up the chemical and accumulated it inside their bodies. In the spring, robins migrated to these areas, fed voraciously on the earthworms, and were poisoned by ingesting high amounts of DDT (INFOGRAPHIC M6.2).

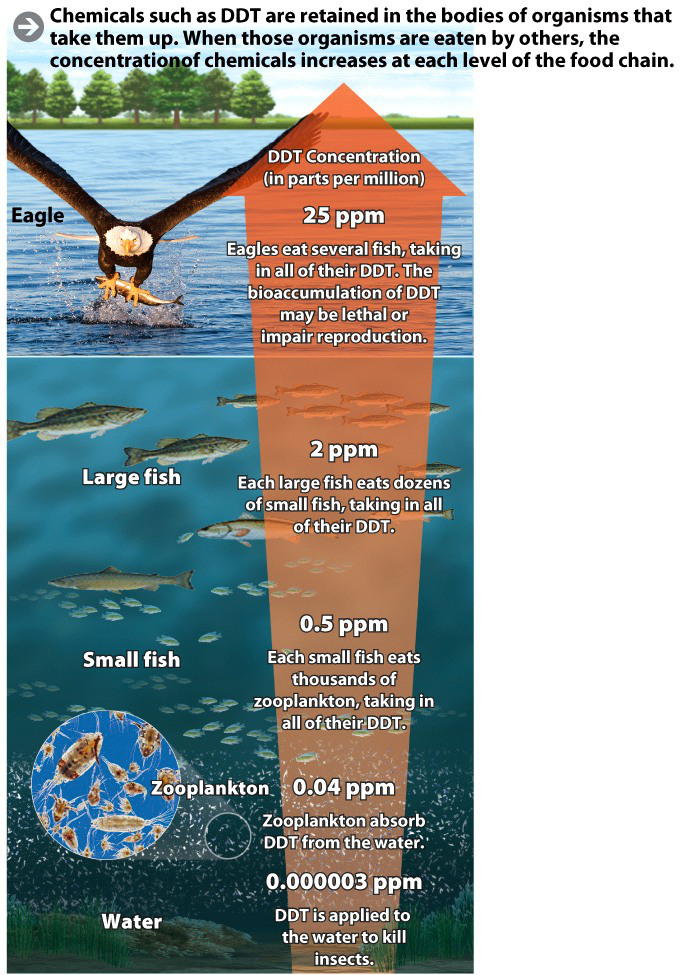

Carson presented evidence that aquatic ecosystems are also affected by DDT. Since 1945, coastal waters around the United States had been sprayed with DDT to combat the salt-marsh mosquito. DDT entered the water supply, where it and its breakdown product DDE were taken up into the bodies of small fish and crabs. Larger fish would eat the smaller fish, thus taking in higher quantities of stored DDT and DDE, until, finally, the larger fish were eaten by top predators like eagles, which ingested the highest quantities of all. Because of the interactions of organisms at different trophic levels in a food chain (see Chapter 22), organisms at the highest trophic levels can have high concentrations of DDT in their tissues even if they were not directly exposed to DDT. The process by which environmental toxins accumulate as they move up the food chain is called biomagnification (INFOGRAPHIC M6.3).

The accumulated DDE impaired reproduction in birds of prey: their eggshells became so thin that mothers would crush their eggs when they sat on their nests to incubate them. From numbers in the hundreds, the eagle population in the United States plummeted in the 1950s and appeared on the verge of extinction—an ominous fate for our national emblem.

Besides the threat to wild animals, Carson also pointed to possible dangers to humans. Though DDT was deemed safe for use as an insecticide on humans, there were concerns about long-term effects. “We have to remember that children born today are exposed to these chemicals from birth, perhaps even before birth,” Carson said in a 1962 interview on CBS News. “Now what is going to happen to them in adult life as a result of that exposure? We simply don’t know.” These uncertainties were made more unnerving when DDT was shown to persist in the environment for many years, long after its application. We now know that DDT persists for at least 15 years in soil and much longer in aquatic environments, possibly for hundreds of years. (The EPA currently classifies DDT as a “probable carcinogen”; DDT bioaccumulates in human tissues and in breast milk, and has been associated with neurological disorders in places where it has been used heavily to treat malaria.)

To Carson, the most galling and stupefying aspect of all these stories was the blind faith people put in pesticides—using them even when they had not been tested and when other methods had proved effective. As a means of controlling Dutch elm disease in the Midwest, for example, DDT spraying was a colossal failure; it did not save the trees, and may have actually made the problem worse because it had the unintended effect of killing birds that serve as a natural form of pest control. Yet effective means of controlling the disease—through removal and burning of contaminated wood—had been used successfully for decades in other parts of the country, for example in New York.

How to account for these lapses of scientific judgment? A big part of the problem, Carson argued, was an unquestioned faith in the power of experts to control nature, bend it to their whim with technology. In other words, it was as much a mind-set as a specific technology that was the source of the trouble.

Can anyone believe it is possible to lay down such a barrage of poisons on the surface of the earth without making it unfit for all life?

Can anyone believe it is possible to lay down such a barrage of poisons on the surface of the earth without making it unfit for all life?

—RACHEL CARSQN

“Who has made the decision that sets in motion these chains of poisonings, this ever-widening wave of death that spreads out, like ripples when a pebble is dropped into a still pond?” she asked in her book. Carson minced no words with her answer: it was shortsighted individuals in positions of power whose capacity for destruction was not matched by an informed awareness of the associated costs.