DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What is the role of insulin in blood-sugar regulation and diabetes?

- In general terms, what is a hormone?

- What features are shared by type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes, and what features are unique to each type?

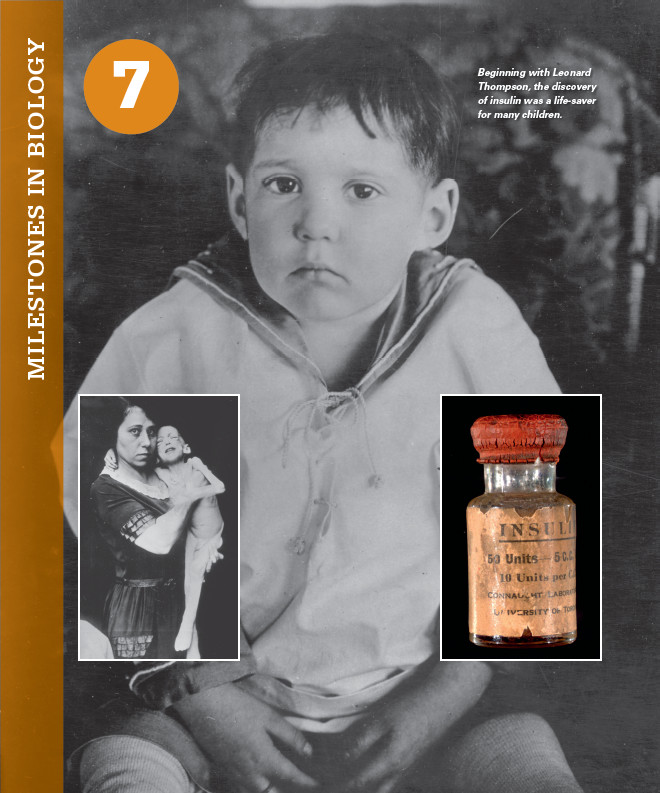

N DECEMBER 1921, A 14-YEAR-OLD BOY NAMED LEONARD Thompson lay sick and dying in a Canadian hospital bed. Weighing just 65 pounds, he was lapsing in and out of consciousness. Elevated levels of sugar in his blood, caused by the disease diabetes mellitus, were wreaking havoc on his internal organs, and doctors told his parents he would likely not survive more than a month. With nothing to lose, Thompson’s parents agreed to let the doctors try something unusual: they injected the boy with a chemical that scientists had recently isolated from the pancreas of a dog. The chemical radically altered Thompson’s fate and that of countless others since.

N DECEMBER 1921, A 14-YEAR-OLD BOY NAMED LEONARD Thompson lay sick and dying in a Canadian hospital bed. Weighing just 65 pounds, he was lapsing in and out of consciousness. Elevated levels of sugar in his blood, caused by the disease diabetes mellitus, were wreaking havoc on his internal organs, and doctors told his parents he would likely not survive more than a month. With nothing to lose, Thompson’s parents agreed to let the doctors try something unusual: they injected the boy with a chemical that scientists had recently isolated from the pancreas of a dog. The chemical radically altered Thompson’s fate and that of countless others since.

For most of human history, diabetes was a dreaded and deadly disease. People with diabetes have unusually high blood-sugar levels–a sign that the body’s cells are not taking up sugar from the blood. Since cells require sugar as fuel to power their activities, this lack of uptake eventually starves the body of nourishment, while the high blood-sugar levels cause a host of problems of their own.

The word “diabetes” comes from the Greek word meaning “to pass through,” and refers to the fact that diabetics tend to urinate excessively. By eliminating excess sugar, urinating restores normal blood-sugar levels. Before there were blood tests, diabetes was diagnosed by testing for the presence of sugar in a patient’s urine, which would often attract flies because it was so sweet (“mellitus” means “like honey”). Until 1921, there was no effective treatment for diabetes, and a diagnosis was in essence a death sentence.

The breakthrough came in a laboratory located just footsteps from where Thompson was being treated at the University of Toronto. A team of upstart researchers, working on a shoestring budget, succeeded where many other scientists had failed. With nothing more than a pack of stray dogs and some borrowed laboratory equipment, they discovered a treatment for millions.