A Rocky Start

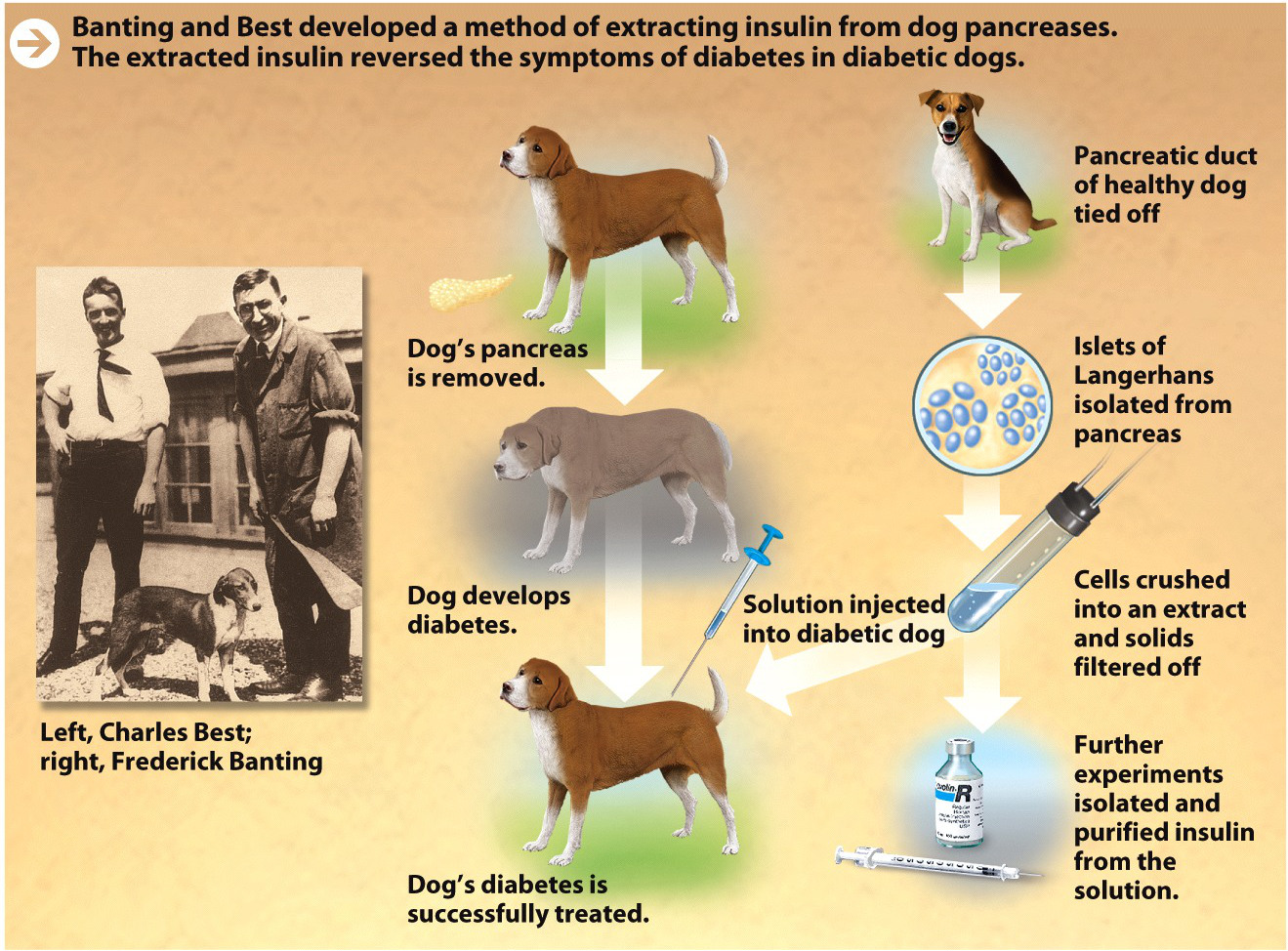

Banting and Best began by performing surgery on dogs to tie off the pancreatic duct. Then, in a few weeks, when the enzyme-secreting part of the pancreas had died, they would remove the Langerhans cells and crush them into an extract. This extract would then be injected into other dogs whose pancreases had been surgically removed, to see if the extract would prevent them from getting diabetes. At least, that was the idea. But it was easier said than done.

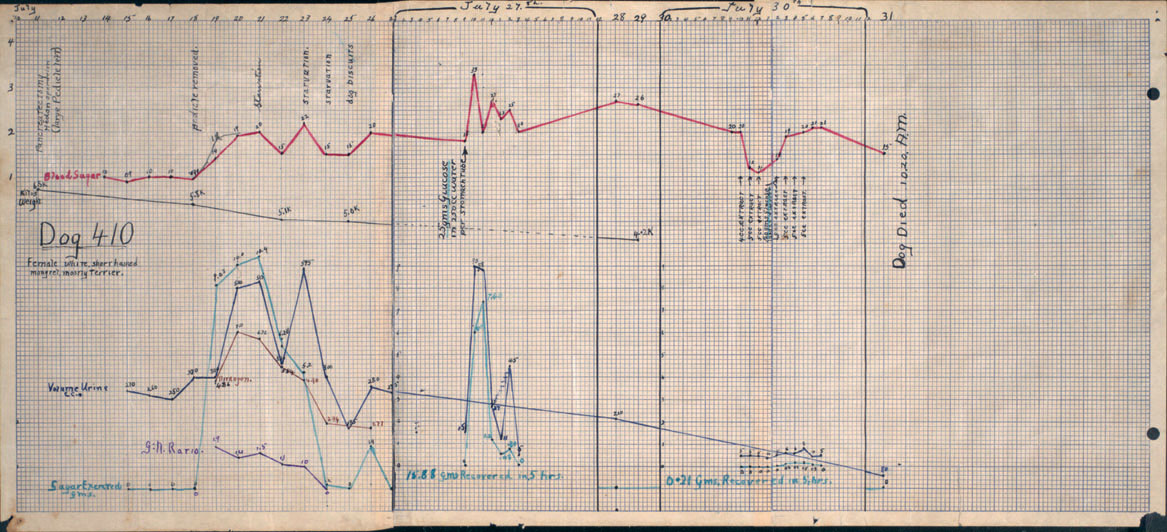

The initial results were disappointing: 7 of the 10 dogs died of complications from the surgery even before the researchers could perform the rest of the experiment. To obtain more research animals, they resorted to buying dogs off the street for $1, no questions asked. Banting practiced the surgery on these new dogs. Finally, he managed to keep the dogs alive long enough to extract the “island” cells. Banting and Best were now ready to inject the extract into another dog made diabetic by removing its pancreas. The procedure worked: the extract significantly lowered the dog’s blood-sugar levels and also reduced the amount of sugar in the dog’s urine. A pancreatic hormone did indeed seem to regulate blood sugar. They reported these results to Macleod, who realized a major breakthrough had been made (INFOGRAPHIC M7.2).

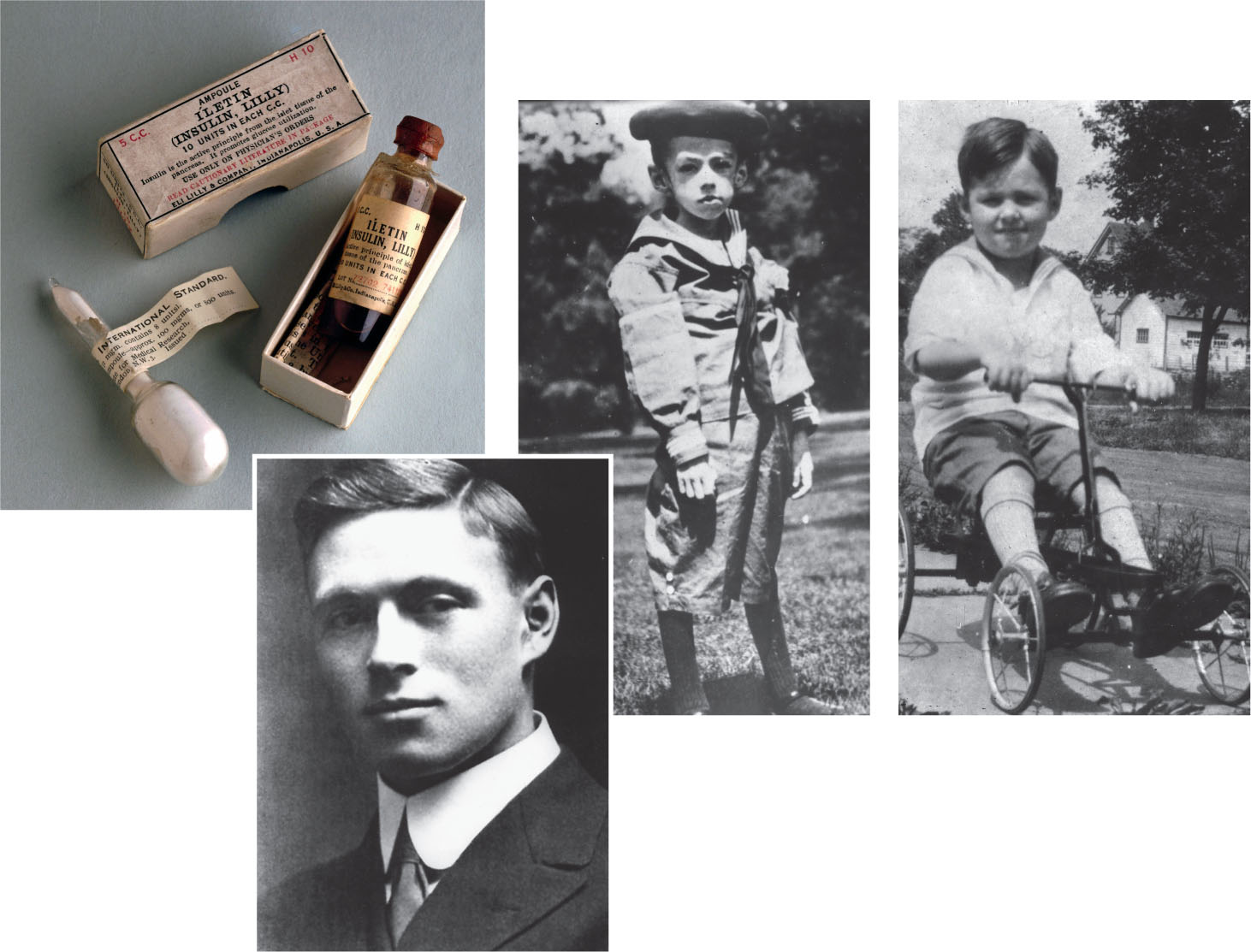

Banting and Best were excited to have discovered the elusive hormone insulin, but it quickly became clear that producing insulin from stray dogs was not a viable way to create a treatment for thousands, and they kept looking for other sources. They discovered that fetal calf pancreas was also an abundant source of insulin. But still there were problems: the insulin prepared from ground-up calf pancreas often produced a severe allergic reaction in the animals who received it. Macleod believed that these reactions were caused because the insulin was impure–mixed with other chemicals of the pancreas. Since neither Banting nor Best was a chemist, Macleod hired a young biochemist, James Collip, to help prepare a more chemically pure version of the drug. Such a cleaned-up version would be needed if the drug were to be used in people.

Eventually, using a method that included alcohol and evaporation, Collip was able to produce a pure form of the drug, and the team was ready to test insulin on humans. They talked to doctors at the hospital across the street at the University of Toronto, who were desperate for a new way to treat patients with diabetes. Leonard Thompson, the 14-year-old diabetic patient who was falling in and out of consciousness, received this purified version on January 23, 1922. Within moments, he was alert and smiling, to the astonishment of his parents. Encouraged by these results, the doctors next went from bed to bed in the diabetes ward, injecting one patient after another. Before they reached the last patient, the first patients to be injected were regaining consciousness. Insulin as a treatment for diabetes was born.