Chapter Introduction

CHAPTER 10

COMMUNITY ECOLOGY

WHAT THE STORK SAYS

A bird species in the Everglades reveals the intricacies of a threatened ecosystem

CORE MESSAGE

Ecological communities are complex assemblages of all the different species that can potentially interact in an area. All the pieces of the ecological community are connected; change one thing, and many others are affected. This means ecosystems are often negatively affected by human impact. Understanding the interconnections within the communities may allow us to better protect and even help restore damaged ecosystems.

AFTER READING THIS CHAPTER, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO ANSWER THE FOLLOWING GUIDING QUESTIONS

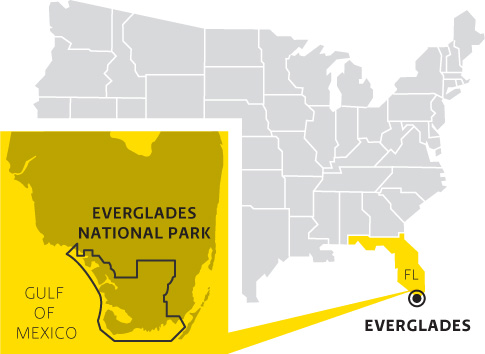

James Rodgers steered his canoe toward a large cypress tree as sunlight trickled through the dizzy pattern of leaves overhead. The tree had several wood stork nests in it, and Rodgers and his assistant wanted to get a closer look at all of them. They were in the thick of a dense swamp near the northwestern edge of the Florida everglades, and it was the height of breeding season for the storks—eggs had hatched, and nestlings everywhere were crying, loudly, for food. Rodgers was silent. He knew from experience that alligators patrolled the waters surrounding stork nests and that too much human disturbance could “flush” the adult storks—forcing them to flee in a hurry, which would leave their babies vulnerable to aerial predators.

The wood stork is an unassuming sort of bird: More than 1 meter (3 feet) tall, yes. But also covered with a mottled black-and-white coat of feathers—bland compared to some of its tropical neighbors. Despite the lack of majesty of the wood storks, however, Rodgers and others at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Service keep close tabs on their ranks.

Here’s why: In the late 1970s, the number of nesting pairs of the bird plummeted to an all-time low of 4,500 or so. By the early 1980s, the bird had earned a spot on the endangered species list. It was then that Rodgers and his colleagues were first tasked with determining which of several factors (Reduced nesting habitat? Health of females? Damaged feeding grounds?) was most responsible for the decline of this particular bird. And it was through those research efforts—focused intently on the wood stork—that they found an entire ecosystem on the brink.