Matter and energy move through a community via the food web.

As ecologists would soon discover, the loss of even one species can disrupt an entire ecosystem—from the health of giant wading birds right down to the movement of matter and energy.

Energy is the foundation of every ecosystem; it is captured by photosynthetic organisms and then passed from organism to organism via the food chain—a simple, linear path that shows what eats what. Any given ecosystem might have dozens of individual food chains. Linked together, they create a food web, which shows all the many connections in the community. Both food chains and webs help ecologists track energy and matter through a given community. They can vary greatly in length and complexity between different types of ecosystems. But most share a few common features, and all are made up of the same basic building blocks—namely, producers and consumers.

food chain

A simple, linear path starting with a plant (or other photosynthetic organism) that identifies what each organism in the path eats.

food web

A linkage of all the food chains together that shows the many connections in the community.

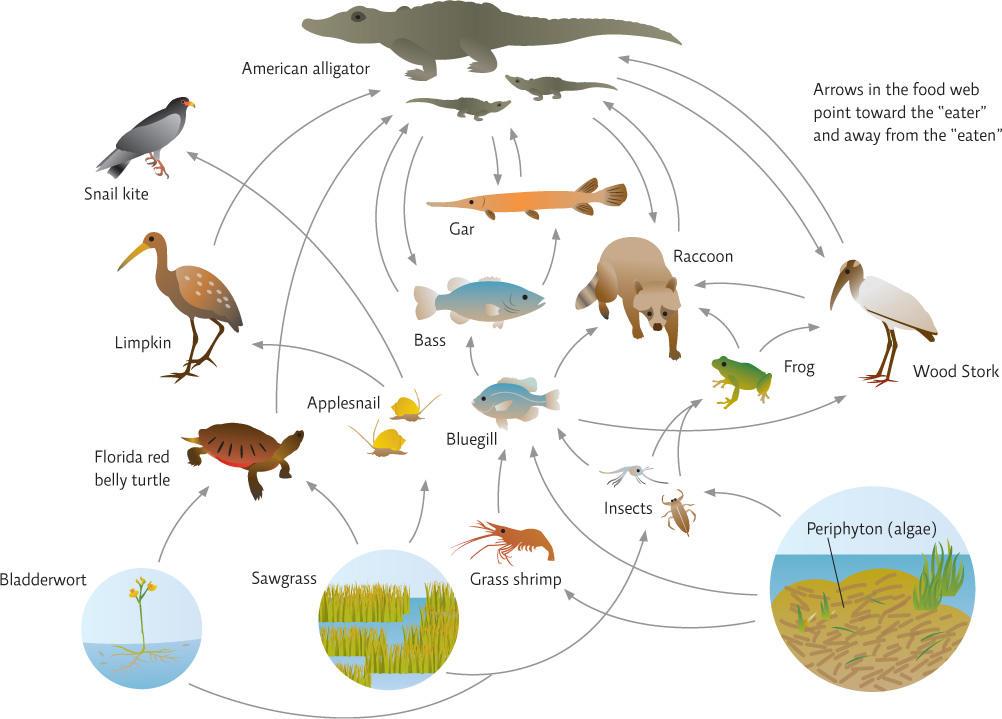

Florida wood storks sit near the top of a food chain that begins with sawgrass, other plants like cypress and mangrove trees, and a mix of algae and bacteria known as periphyton. These photosynthetic organisms are all known as producers. Producers capture energy directly from the Sun and convert it to food (sugar) via photosynthesis (see Chapter 8). They are then eaten by a wide range of consumers—organisms that gain energy and nutrients by eating other organisms. Animals, fungi, and most bacteria and protozoa are consumers. INFOGRAPHIC 10.1

producer

An organism that captures solar energy directly and uses it to produce its own food (sugar) via photosynthesis.

consumer

An organism that eats other organisms to gain energy and nutrients; includes animals, fungi, most bacteria.

The food web of the Everglades is very complex and varies among the different ecosystems found there. Periphyton algae mats form the base of the food web and may be the most important producers in the ecosystem. The American alligator is the main apex predator, though when young is also prey to various birds, fish, mammals, and even other alligators.

Identify two or three food chains within this web that end with the alligator.

There are many possible food chains such as: sawgrass -- apple snail -- limpkin -- alligator OR periphyton ---grass shrimp --- bluegill -- bass -- gar -- alligator OR bladderwort -- insects --frog -- wood stork -- alligator

KEY CONCEPT 10.2

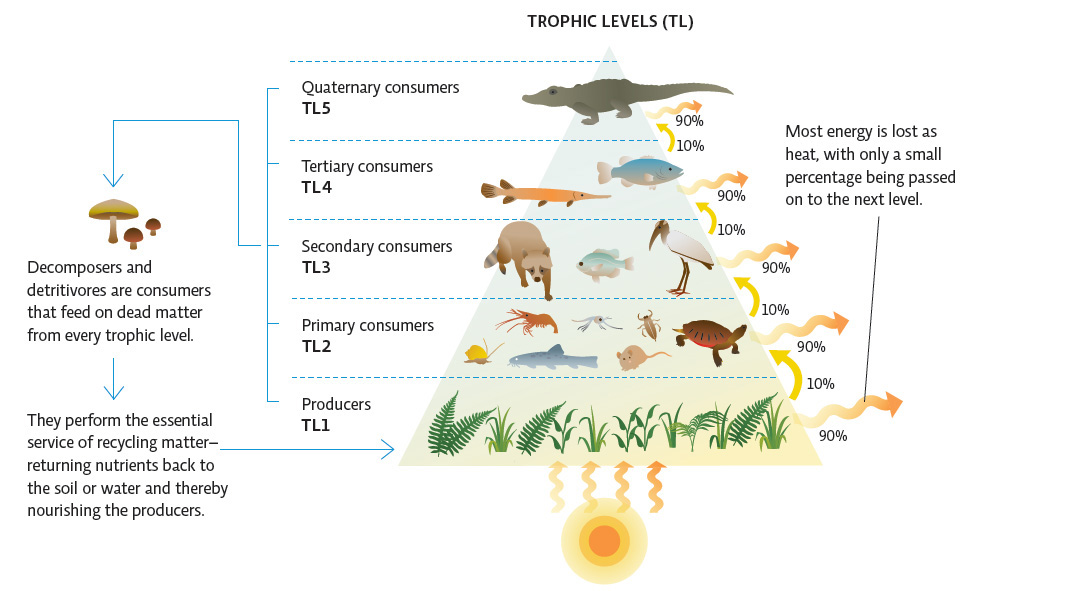

Producers capture energy, which is used or passed on to consumers via the food chain. The biomass of trophic levels decreases as one moves up the trophic pyramid because organisms use most of the energy taken in and pass only a small percentage on to the next level.

These different feeding levels are known as trophic levels. Consumers are organized into trophic levels based on what they eat. Primary consumers eat producers; secondary consumers eat organisms on lower trophic levels, predominately feeding on primary consumers; tertiary consumers primarily (or exclusively) eat secondary consumers, and so on, ending with the apex predators in the last trophic level. Of course, many consumer species often feed at more than one trophic level: Wood storks eating crayfish are feeding at trophic level 3, but when they eat small fish like bluegill, they are feeding at trophic level 4.

trophic levels

Feeding levels in a food chain.

In an ecosystem as diverse and complex as the Everglades, there are dozens of different organisms at each trophic level, making for a wide variety of food chains. For example, periphyton might be eaten by grass shrimp (a primary consumer), which in turn might be eaten by bluegill (a secondary consumer), who fall prey to raccoons (tertiary consumers), who might be eaten by alligators (quaternary consumers). Alligators eat a wide variety of animals—turtles, fish, birds, even mammals like the raccoon—making them the apex predator in many Everglades food chains.

When any of these organisms die, they are eaten by an army of consumers known as detritivores—animals like worms, insects, and crabs that feed on dead plants and animals—and decomposers—organisms like bacteria and fungi that break decomposing organic matter all the way down into its constituent atoms and molecules.

detritivores

Consumers (including worms, insects, crabs, etc.) that eat dead organic material.

decomposers

Organisms such as bacteria and fungi that break organic matter all the way down to constituent atoms or molecules in a form that plants can take back up.

As one moves up the food chain, energy and biomass (all the organisms at that level) decrease, creating a trophic pyramid. The reason is simple: Nearly every organism uses up the majority of its energy and matter in the complicated act of living. So when an organism is killed and consumed by a predator, it only passes on a small percentage of all the energy and matter it consumed during its lifetime. INFOGRAPHIC 10.2

Energy enters at the base of the food chain in the first trophic level (TL) via photosynthesis and is passed on to higher levels as consumers feed on other organisms. This is shown as a pyramid (smaller on top) because only a small percentage of the energy is passed on to each higher level, with the majority being “lost” to the environment (usually as heat from the energy that the organism burns in day-to-day life before it is eaten). Most food chains have only four or five levels due to this progressive loss of energy. Though the actual amount varies from ecosystem to ecosystem, for illustration purposes, we show 10% passing on to the next higher level.

Why are there seldom more than five tropic levels?

The number of trophic levels is limited by the size of the producer level. Since only a small percentage of energy is passed on from one trophic level to the next, by the time the 4th or 5th level is reached, very little of the original energy captured by the producers is available. Communities with larger producer bases (more plant biomass) can potentially support more trophic levels because there is more energy there is to start with, therefore, more remains to be passed on with each pass to a higher trophic level. In other words, even if only 10% is passed on, if it is 10% of a very large amount, the absolute amount of energy reaching the 5th or even 6th level will be enough to support that trophic level.

KEY CONCEPT 10.3

Matter also moves through the food chain and eventually makes its way back to producers, where it can be used again, thanks to the action of detritivores and decomposers.

A pyramid’s ultimate size is determined by its first trophic level—the one made up of photosynthesizing producers, namely plants. More plant growth means more food for primary consumers, which in turn means more food for those organisms above them, and so on up the food chain. The end result is a larger pyramid with more and larger trophic levels.

The amount of energy trapped by producers and converted into organic molecules like sugar is called productivity and is limited by sunlight and nutrient availability. Gross primary productivity is a measure of total photosynthesis. But plants use only a portion (actually less than 50%) of this energy to fuel their daily needs; the rest goes to growth. Scientists use the term net primary productivity (NPP) to describe that left-over energy—the energy that fuels the addition of new plant biomass (growth). The “net” is a measure of energy available to higher trophic levels. Terrestrial NPP is highest in tropical forests due to high year-round photosynthesis. Equaling or surpassing these tropical forests’ NPP is that seen in wetlands and estuaries (aquatic habitats where rivers meet oceans), especially tropical ones. Favorable temperatures, high levels of nutrients, and abundant water supplies make these the most productive ecosystems on Earth.

gross primary productivity

A measure of the total amount of energy captured via photosynthesis and transferred to organic molecules in an ecosystem.

net primary productivity (NPP)

A measure of the amount of energy captured via photosynthesis and stored in a photosynthetic organism.

KEY CONCEPT 10.4

Ecosystems with a lot of habitat variety and niches can accommodate more species diversity, and this, in turn, increases the resilience of the community.

The Everglades are blessed with long summer days that favor plant and algal photosynthesis. But in many other ecosystems, winter months cast the downside of sunlight dependence into stark relief. In most temperate and boreal forests, for example, less sunlight and cooler temperatures limit photosynthesis during these months, causing plant productivity to slow or shut down completely, resulting in less new growth and thus less food for other organisms. This is why bears hibernate and birds fly south for the winter: The lack of productivity drives them to these extremes. NPP can be a window into the health of an ecosystem. If it rises or falls unexpectedly, ecologists can look for the cause of the change, which might be an invasion by a non-native plant or a sudden drop in a producer population. Anything that alters NPP can potentially affect organisms at every other level of the trophic pyramid.

As researchers discovered in the 1980s, it was a kink in the food chain that hurt the wood storks. While they feed on many things, they prefer fish—and not just any fish, but those between 2 and 15 centimeters (1 and 6 inches) long. Most fish need more than a single season to grow this big; in fact, they need wetlands that are flooded for longer than a year and only very rarely go completely dry. It turns out that as humans altered water cycles in South Florida, there were fewer and fewer such areas, and thus fewer fish for the storks to feed their young.