Species interactions are extremely important for community viability.

Communities are all about relationships. Successful communities are those where a certain balance has evolved between all the organisms living there. Species interactions serve many purposes; for example, they control populations and affect carrying capacity. Biodiversity (lots of species, lots of variety within a species) is important because more diversity means more ways to capture, store, and exchange energy and matter (see Chapter 12). But it is not sheer numbers that matter most; it is all the connections among species—how they help or hurt one another—that determine how and how well an ecosystem works. Each species is unique and thus interacts in its own unique ways with all the species around it.

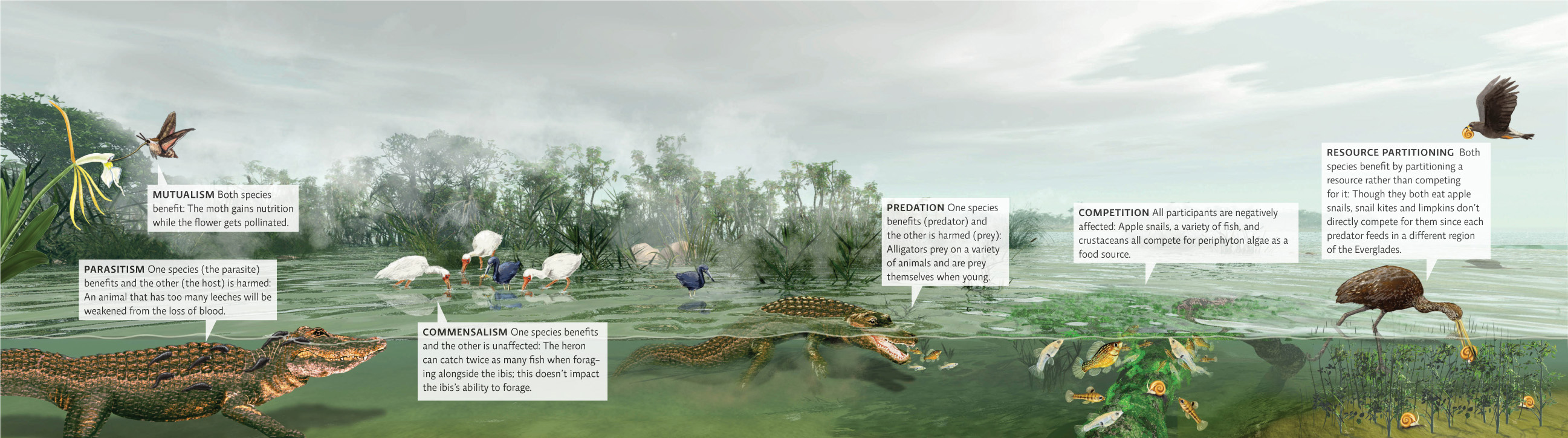

Many species have adaptations that bind them to others, that allow them to coexist, or that facilitate predation. In the Everglades, for example, alligators have adaptations—like sharp teeth and powerful jaws—that allow them to stalk and capture prey while most of the fish they prey on have adaptations—like camouflage and a wary nature—that help them avoid capture.

predation

Species interaction in which one individual (the predator) feeds on another (the prey).

Competition—the vying between organisms for limited resources—is another way that species interact. In general, it is subtle rather than outright fighting. Intraspecific competition (that which occurs between members of the same species) is generally stronger than interspecific competition (that which occurs between members of different species). This is because members of the same species share exactly the same niche and thus compete for all resources in that niche, whereas members of different species may compete for only a single resource, like water.

competition

Species interaction in which individuals are vying for limited resources.

Other neighbors—those that prey on the same food or inhabit similar niches—find a way to partition resources. That is, they divvy up the goods in a way that reduces competition and allows several species to coexist. For example, limpkins and snail kites (two Everglades birds that feed almost exclusively on apple snails) hunt in different regions of the Everglades. This strategy—known as resource partitioning—increases the ecosystem’s overall capture of matter and energy and thus benefits the entire community.

resource partitioning

A strategy in which different species use different parts or aspects of a resource rather than compete directly for exactly the same resource.

There are other strategies, too, that keep an ecosystem functioning and strong.

Some of these interactions show a tremendous interdependency on the part of the participants. Known as symbiosis, these relationships can take one of three forms. The most commonly recognized form of symbiosis is mutualism, where both species benefit from the relationship. In the symbiotic relationship known as commensalism, one species benefits from the relationship, and the other is unaffected. Even parasitism, where one species benefits from the relationship and the other is negatively affected, is a form of symbiosis. INFOGRAPHIC 10.7

symbiosis

A close biological or ecological relationship between two species.

mutualism

A symbiotic relationship between individuals of two species in which both parties benefit.

commensalism

A symbiotic relationship between individuals of two species in which one benefits from the presence of the other, but the other is unaffected.

parasitism

A symbiotic relationship between individuals of two species in which one benefits and the other is negatively affected.

The heart of a functioning community is its species interactions. Some interactions are beneficial and others cause conflict, but all are important in keeping matter and energy flowing through an ecosystem.

Choose an ecosystem other than the Everglades and give examples of mutualism, commensalism, parasitism, predation, competition, and resource partitioning.

Answers will vary depending on the ecosystem chosen.

By ensuring that all populations persist, even as individuals die, these delicate checks and balances allow more energy to be captured and exchanged and thus increase the amount of biomass the ecosystem is able to produce.

As we’ve seen, the wood storks rely on several relationships to survive. Their ability to feed depends not only on very specific wetlands hydrology but also on the health and size of the fish they feed upon. And their ability to raise and fledge young depends not only on the availability of “moated” trees—those surrounded by water—but also on a healthy population of alligators that can patrol those moats for raccoons. When individual species are lost, or when a landscape is physically altered, the balance is tipped. And when that happens, things can fall apart. Fast.