Ecologists and engineers help repair ecosystems.

The federal 1992 Water Resources Development Act enlisted the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to investigate the damage to the Everglades that resulted from nearly 50 years of unchecked expansion. The final report, published in 1999, acknowledged that the original Everglades (as we found them upon first exploration in the late 1800s) had been reduced by 50%. Human impact often simplifies ecosystems by decreasing the habitat variety normally seen, which leads to a decrease in species diversity. Constructed canals and levees had dramatically altered water levels, leaving some areas parched and others flooded. And poorly timed water releases were further starving ecosystems that had already been affected by hypersalinity, excessive nutrients (from agricultural runoff), and an ever-growing list of non-native species.

KEY CONCEPT 10.8

Human impact often reduces species diversity. It may be difficult to restore all the species and their connections when we try to repair ecosystem damage; therefore, our best course of action is to avoid the damage in the first place.

Ignoring these problems any longer could greatly imperil the 10 million people that had made their home in the region. “What folks finally realized when we reexamined the area was that the wetlands were this essential filter—they cleaned the water of pollutants,” says Kim Taplin, a restoration ecologist who works for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, restoring the Florida wetlands. “So as the ecosystems have suffered, water quality has declined considerably. We’re going to have millions of people with no clean water, unless we fix it.” Avoiding the ecosystem damage in the first place is almost always our best option, but when damage is done, fixing it is the work of restoration ecologists. Restoration ecology is the science that deals with the repair of damaged or disturbed ecosystems. It requires a special blend of skills—not only biology and chemistry but also engineering and a heavy dose of politics.

restoration ecology

The science that deals with the repair of damaged or disturbed ecosystems.

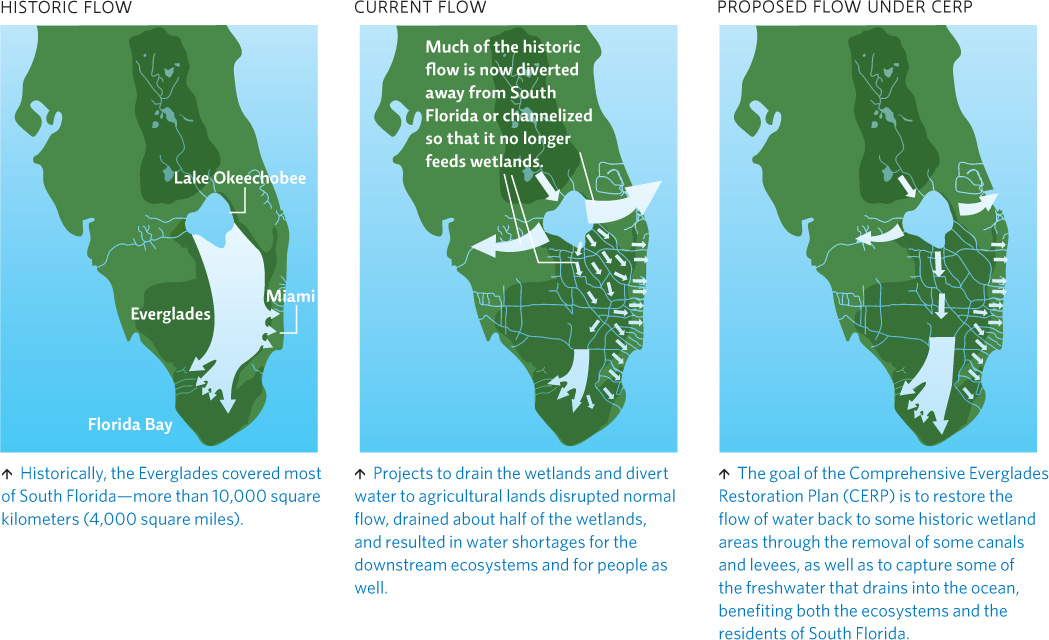

In 2000, the U.S. Congress enacted the most comprehensive—and expensive—ecological repair project in history. The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, or CERP, included more than 60 construction projects to be completed over a 30-year period. The idea was to restore some of the natural flow of water through the Everglades and to capture a portion of the water that now flows to the ocean for South Florida cities and farms.

One of the Army Corps’ biggest challenges has been to take down at least part of the Tamiami Trail, a 240-kilometer (150-mile) stretch of U.S. highway that connects the South Florida cities of Tampa and Miami. The road, which was built in the 1920s, has proven to be one of the most serious barriers to freshwater flow in the region. It’s also a heavily traveled, essential piece of human infrastructure that connects two major cities. That means the U.S. Army Corps must not only tear down the road but also build something in its place. “Most of our restoration projects involve building even more structures,” says Tim Brown, project manager for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Tamiami Trail project. “It’s a delicate balance. We of course want to restore as much of the natural system as possible. But we are also charged with protecting lives and property, and in this case, that means building bridges.”

“We’re going to have millions of people with no clean water, unless we fix it” —Kim Taplin.

Dismantling the Tamiami Trail is not the only plan in the works. In 2008, the state of Florida agreed to buy U.S. Sugar Corporation and all of its manufacturing and production facilities in the Everglades Agricultural Area south of Lake Okeechobee for roughly $1.7 billion. State officials declared that they would allow U.S. Sugar to operate for 6 more years before shuttering facilities and beginning the work of restoration. After that, water flow from Lake Okeechobee would be funneled through a series of holding and treatment ponds that would release clean water into the Everglades, rehabilitating some 187,000 acres of land. But the agreement has been revised several times since then, as the economy has fluctuated and state officials and sugar executives have adjusted and readjusted exactly how many acres would be bought for exactly how many dollars. The proposed purchase was hotly debated, as many feared the cost would take money away from other Everglades restoration projects. In October 2010, just under 11,000 hectares (27,000 acres) were purchased for $197 million, with a 10-year option to acquire another 62,000 hectares (153,200 acres). However, U.S. Sugar is still farming part of the land, leasing it back from the state. The timetable for U.S. Sugar to stop farming the land has been pushed back three times since the 2010 deal was signed; farming is currently slated to end on the land in 2018, after which restoration can begin. In the meantime, the state of Florida failed to meet an October 2013 deadline to purchase the additional 153,200 acres from U.S. Sugar at only $7,400 per acre. The state still has the option to purchase the land up to the year 2020, but at market value.

Each facet of CERP has brought its own fresh round of debate over how best to balance the needs of a swelling human population against the importance of restoring and protecting a heavily degraded ecosystem. Of course, no one knows for certain what will work and what won’t. The Everglades landscape has changed dramatically, in ways that not even the best scientists can reverse; decades of development will do that. To plan effective restoration efforts, then, scientists and engineers must be flexible; they must be willing to experiment and respond as conditions change—an adaptive management approach similar to that used to address stratospheric ozone depletion (see Chapter 2). INFOGRAPHIC 10.8

Darker green areas represent wetland areas or river floodplains; white arrows show overland water flow.

Explain how rerouting some of South Florida’s water flow back through the center of the state, through restored wetlands, will help provide residents with more drinking water.

Rerouting the water so that more of it flows through an inland wetland will slow that flow and allow more of the water to soak into the ground, replenishing ground water supplies.

“The bottom line, though, is that there’s only so much we can do,” says Rodgers. “It’s a lot just to figure out what the baseline was or should be. Some plant species have probably gone extinct, and some non-natives are virtually impossible to remove. What we can do is figure out what some of the big obstacles to recovery are, remove them, and after that, let nature take its course.” For his part, Rodgers says he can’t imagine that the great 1,000-breeding-pair wood stork colonies that early settlers described will ever return to South Florida. The landscape has been too dramatically altered, he says. Though, sometimes, of course, nature can surprise us.