Community composition changes over time as the physical features of the ecosystem itself change.

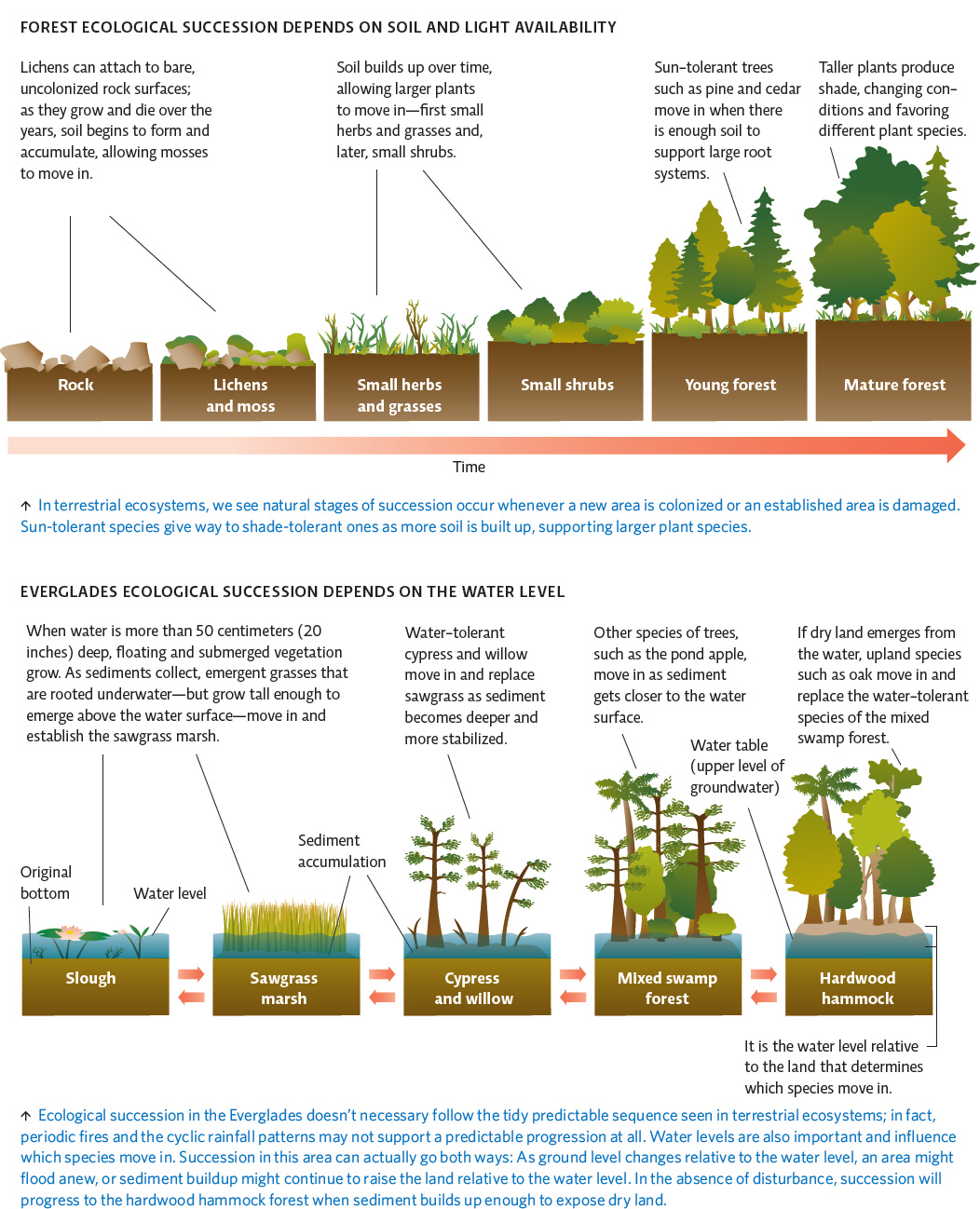

Though the changes the Everglades have experienced are extreme, changes to ecological communities are really the norm; nature is not static. Predictable transitions can sometimes be observed in which one community replaces another, a process known as ecological succession. Primary succession begins when pioneer species move into new areas that have not yet been colonized. In terrestrial ecosystems, these pioneer species are usually lichens—a symbiotic combination of algae and fungus. Lichens can tolerate the barren conditions. As time goes by and lichens live, die, and decompose, they produce soil. As soil accumulates, other small plants move in—typically sun-tolerant annual plants that live 1 year, produce seed, and then die—and the plant community grows. Gradually, the plant growth itself changes the physical conditions of the area—covering sun-drenched regions with broad, shady leaves, for example. Since these conditions are no longer suitable for the plants that created them, new species move in, and those changes beget even more changes until the pioneers have been completely replaced by a succession of new species and communities.

ecological succession

Progressive replacement of plant (and then animal) species in a community over time due to the changing conditions that the plants themselves create (more soil, shade, etc.).

primary succession

Ecological succession that occurs in an area where no ecosystem existed before (e.g., on bare rock with no soil).

pioneer species

Plant species that move into an area during early stages of succession; these are often r species and may be annuals—species that live 1 year, leave behind seeds, and then die.

KEY CONCEPT 10.9

Over time, ecosystems naturally transition from one community to another in response to changing environmental conditions. An understanding of this ecological succession process can guide our restoration efforts.

Secondary succession describes a similar process that occurs in an area that once held life but has been damaged somehow; the level of damage the ecosystem has suffered determines what stage of plant community moves in. For example, a forest completely obliterated by fire may start close to the beginning with small herbs and grasses, whereas one that has suffered only moderate losses may start midway through the process with shrubs or sun-tolerant trees moving in. The stages are roughly the same for any terrestrial area that can support a forest: first annual species, then shrubs, then sun-tolerant trees, then shade-tolerant trees. Grasslands follow a similar pattern, with different species of grasses and forbs (small leafy plants) moving in over time.

secondary succession

Ecological succession that occurs in an ecosystem that has been disturbed; occurs more quickly than primary succession because soil is present.

We tend to view this progression as a “repair” sequence. While we can certainly step in to assist in this natural progression to help a damaged ecosystem recover to a former state, the ecosystem is simply doing what comes naturally—responding to changing conditions.

Intact ecosystems have a better chance at recovering from, and thus surviving, perturbations. As mentioned earlier, ecosystems that recover quickly from minor perturbations are said to be resilient: They can bounce back. More species-diverse communities tend to be more resilient than simpler ones with fewer species because it is less likely that the loss of one or two species will be felt by the community at large; even if some links in the food web are lost, other species are there to fill the void. Of course, if keystone species are lost, the community will feel the effect. The loss of the alligator from the complex Everglades community would impact many species and change the face of the ecosystem.

Some ecosystems remain in a constant cycle of succession; others eventually reach an end-stage equilibrium where the conditions are well suited for the plants that created them—for example, trees whose seedlings can grow in shady habitat. These species, which can persist if their environment remains unchanged, are called climax species. End-stage climax communities can stay in place until disturbance restarts the process of succession—although there is debate among scientists over whether any community ever reaches an end point of succession or continues to change and adapt.

climax species

Species that move into an area at later stages of ecological succession.

Wetland areas also go through succession, responding to the presence of water and sediment depth. In the Everglades, each ecosystem is guided along this path by its own constellation of forces. Some, like the iconic sawgrass ecosystems, are fire adapted; fire returns them to early stages again and again, where the underwater roots of the emergent plants (those that are rooted underwater but grow above the waterline) such as sawgrass survive and quickly regrow. Others, if left undisturbed, would pass through successional stages of pioneers (grasses) to shrubs or small trees to larger species of trees, depending on the deposition of soil and proximity of the water table to the surface (the top of the groundwater in the area). Others still are guided by the engineering changes of animals such as alligators, whose digging habits provide the foundation for an entire food chain. In each, though, the same general concept applies: As conditions change, other species better adapted to those conditions move in and displace previous residents. INFOGRAPHIC 10.9

Look at the forest successional stages shown in the top part of this diagram. Why can’t small shrubs or young trees grow on the land shown supporting small herbs and grasses?

The key here is the amount of soil present. This diagram shows less soil in the herb/grass plot than in the small shrub or young forest plot. Shrubs cannot take root and grow well until there is enough soil. Once enough soil builds up, shrubs can start to colonize an area. Once even more soil builds up, some species of sun-tolerant trees can move in.

However precarious their recovery might be, wood storks have indeed rebounded in recent years. Some say this rebound is the result of careful conservation efforts—including a restriction on development in certain areas—implemented under the U. S. Endangered Species Act. Others insist that it is merely the result of above-average rainfall in recent years. For his part, Rodgers sees another trend at work. Once again, he says, the storks are trying to tell us something. “They have shifted their center of distribution from South Florida to Central and North Florida,” he says. “They’re now spilling into Georgia and North Carolina—something we’ve never seen before.” Rodgers suspects that the shift has something to do with the way climate is changing in the region, though he says much more research is needed before anyone can say for certain. “We’re still trying to figure out what that means,” he says. “But we know it’s a clue to something.”

Select References:

Brix, H., et al. (2010). Can differences in phosphorus uptake kinetics explain the distribution of cattail and sawgrass in the Florida Everglades? BMC Plant Biology, 10: 23.

Rodgers, J. A., et al. (1996). Nesting habitat of wood storks in North and Central Florida, USA. Colonial Waterbirds, 19(1): 1–21.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

The world is full of weird and wonderful species. Every year we discover new information about how intricate our biological communities are. By restoring habitats and increasing our understanding of the relationships between species, we can better ensure their long-term survival.

Individual Steps

•Visit a park or nature preserve and watch for signs of species interactions. Do you hear animals or birds? Can you see signs of predation or herbivory?

•Buy a Duck Stamp. Usually purchased by waterfowl hunters for license purposes, nonhunters can purchase a stamp, which supports wetland conservation in the National Wildlife Refuge System.

Group Action

•The Everglades case study is an example of a very extensive restoration project. Call your local park district or nature preserve to see what restoration work is happening in your area and how you can become involved.

Policy Change

•Follow the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Open Space blog to learn more about wildlife and issues facing conservation (http://www.fws.gov/news/blog).