Biodiversity faces several serious threats.

The world’s biodiversity is threatened from many angles. The scientific consensus is that human actions are behind the high extinction rates of the recent past, especially since 1900. These threats include habitat destruction, the introduction of invasive species (see Chapter 11 for a detailed example), pollution, overharvesting (for consumption, the pet trade, and legal and illegal body parts, such as hides, tusks, and bones), and anthropogenic climate change. Many of these threats are related to overpopulation and affluence that leads to greater resource use. (See Chapter 13 for more on threats to biodiversity.)

KEY CONCEPT 12.6

Human impact, especially habitat destruction and fragmentation, is a major threat to biodiversity, endangering ecosystems and the species (including humans) that depend on the ecosystem services these areas provide.

At least part of the surge in palm oil use—and the habitat destruction it engenders—can be traced back to 2007, when then New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg famously banned the use of hydrogenated oils, which contain high quantities of trans fats, in all New York City restaurants. The ban was well intentioned: Obesity rates were high in the city and in the United States as a whole, and trans fats are, well, fattening. They’re also artery-clogging, heart attack—inducing, and all-around unhealthy to consume, and in 2007, they were pervasive. Seeing the writing on the wall, popular food brands, including Oreo and Dunkin’ Donuts, followed Bloomberg’s lead by voluntarily replacing hydrogenated oil with the next best alternative: palm oil.

Despite the sweet sugary tastes those brand names evoke, palm oil itself has no flavor. What it does have is a soft, thick texture that remains fantastically stable across many temperatures. This thickness and stability make palm oil so useful. It keeps donuts firm and Oreo cookie filling from melting into drizzle. It keeps cosmetics and detergents and peanut butter and Girl Scout cookies consistent and solid at room temperature.

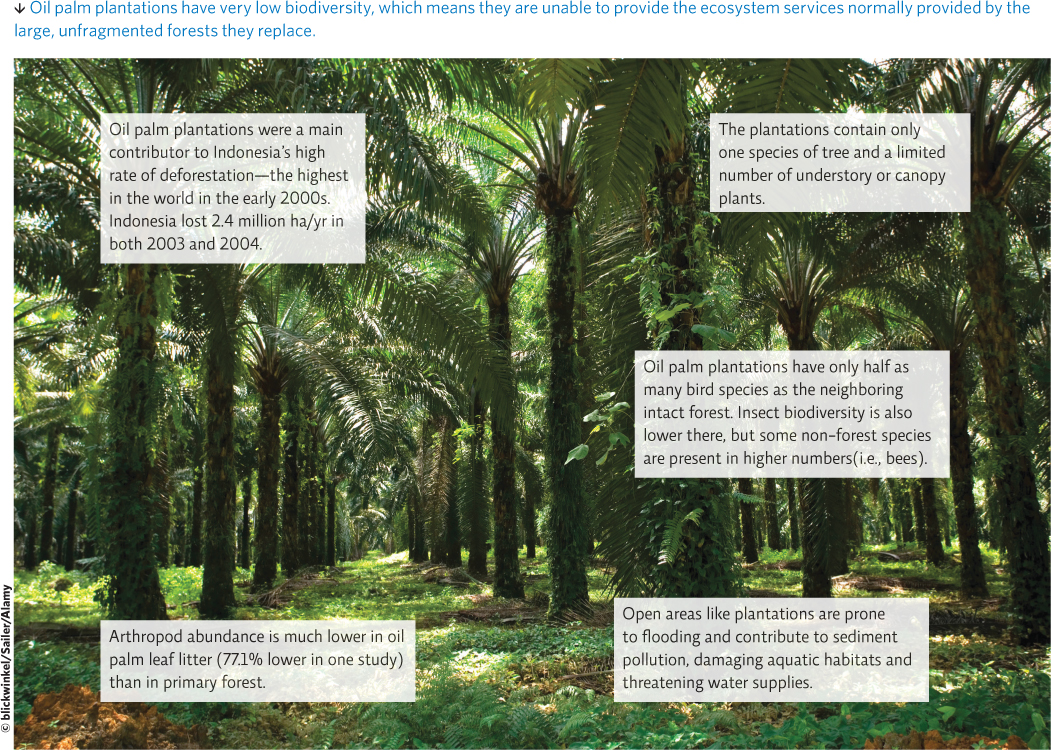

Our palm oil obsession has contributed to the number-one cause of species endangerment: habitat destruction. Other drivers of habitat destruction include urban and suburban development, resource extraction (not just timber harvesting but also mineral mining and fossil fuel extraction), and large water projects such as dams that destroy terrestrial and aquatic habitats. By obliterating certain parts of an ecosystem, habitat destruction makes that ecosystem physically less diverse, which then makes it less biodiverse. This loss of biodiversity, in turn, leads to a reduction of ecosystem services. INFOGRAPHIC 12.6

habitat destruction

The alteration of a natural area in a way that makes it unsuitable for the species living there.

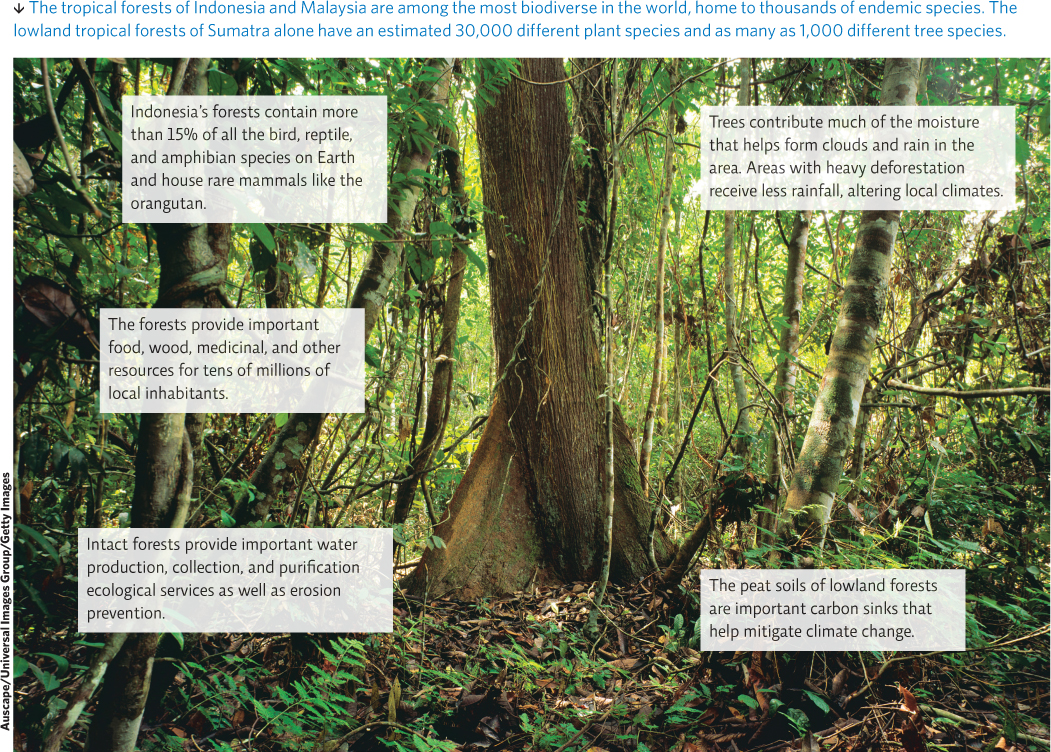

The tropical forests of Indonesia and Malaysia are among the most biodiverse in the world, home to thousands of endemic species. The lowland tropical forests of Sumatra alone have an estimated 30,000 different plant species and as many as 1,000 different tree species.

Auscape/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Describe how tropical forests differ from oil palm plantations in terms of genetic, species, and ecosystem diversity.

The tropical forest will have greater ecosystem diversity and many more niches, some of them created by the higher number of species that live there (more variation in shade, moisture, species themselves that are habitat for others, etc.). The species in the forest will also have greater genetic diversity as individuals breed freely with one another. In the plantation, species diversity is lower - there will only be one tree (the oil palm) and other species will be kept out deliberately or will fail to survive because they have lost suitable habitat (low ecosystem diversity). Genetic diversity of the oil palm will be low (one or only a few varieties planted).

As mentioned earlier, the detrimental impacts of habitat destruction can also be touched off by the loss of even part of a larger habitat, known as habitat fragmentation. Deforestation that leaves patches of forest may not be suitable for species that need large expanses of forest. Some species will simply not cross over the deforested patch to disperse from one side of the patch to the other, so the patches effectively isolate them from other parts of their population. Even a narrow or little-used road may isolate individuals on one side or the other. Wildlife corridors that connect fragmented habitats can be effective conservation tools. Specially constructed road overpasses or underpasses or ribbons of natural habitat that connect two habitat fragments can allow individuals to travel more freely and are vitally important in maintaining genetic diversity in the populations— especially for species that range widely and live at low population densities, such as large carnivores like grizzly bears and wolves.

habitat fragmentation

The destruction of part of an area that creates a patchwork of suitable and unsuitable habitat areas that may exclude some species altogether.

Extinction doesn’t have to be worldwide to have an impact. Species that become extinct locally but not everywhere are said to be extirpated. So, while a species may not technically be extinct (and perhaps not even identified as an endangered species), its extirpation can have serious impacts on its own ecosystem, potentially disrupting the connections that the ecological community depends on, triggering a cascade that threatens other species in the region. “Simple” ecological communities (ones with relatively few species) are much more affected by a single loss. But even “complex” ecosystems (those with many species and many filled niches) can be gravely imperiled if too many members are lost, especially if keystone species are lost. The loss of half of a native plant community is a loss that few, if any, ecosystems can endure without completely collapsing. Of course, once one ecosystem collapses, a new one may emerge. But such recovery takes a very long time.

extirpated

Describes a species that is locally extinct in one or more areas but still has some individual members in other areas.

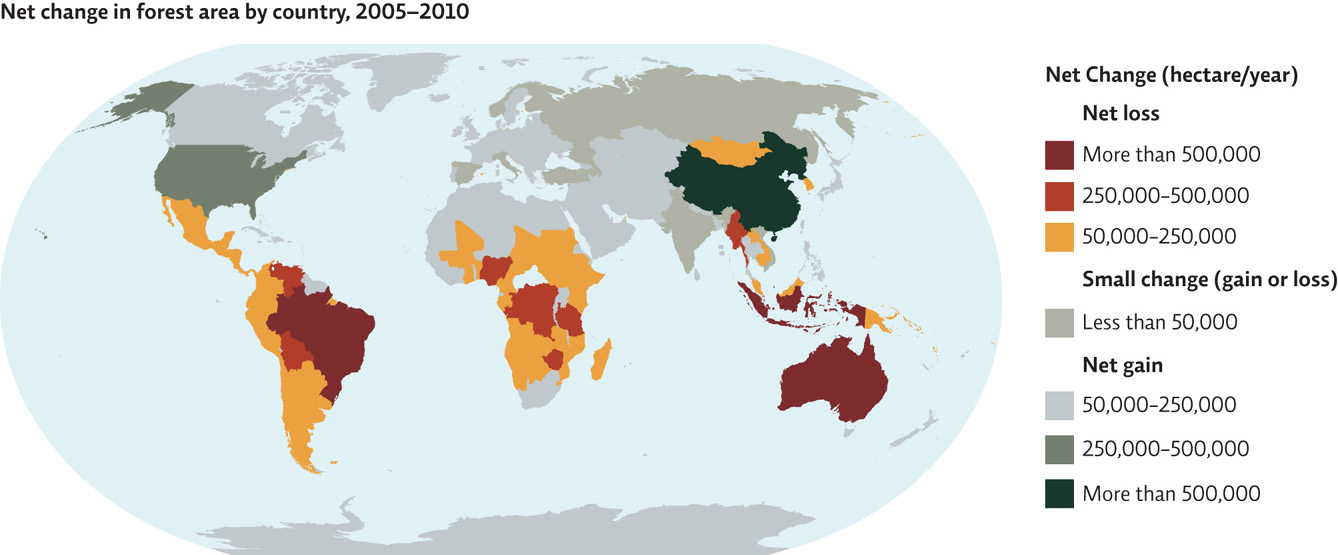

In the tropics, deforestation for agricultural purposes is currently the leading cause of terrestrial habitat destruction. Fragmentation is also a problem for temperate forests due largely to timber harvesting and human development, but, interestingly, some temperate forests have increased in size in recent decades—in part because tropical forests have less political protection and are more easily exploited. Temperate forests in many areas have been restored and are managed for a variety of purposes, including the planting of fast-growing trees that are harvested and then replanted. INFOGRAPHIC 12.7

Deforestation has been highest in tropical areas in recent years. Afforestation projects, including forests planted and managed for timber harvesting, have actually led to an increase in forest cover in North America and China.

What areas show a net gain in forest cover on this map? Which country has experienced the highest net gain? What might be contributing to these gains?

Canada, the United States, all of Europe, much of Asia, and parts of North Africa show a net gain. China shows the highest net gain. Possible reasons for these net gains include: conservation efforts to reforest areas, economic downturns that reduced the need for wood as a raw material, global focus on deforestation in tropical areas reducing the need to harvest trees in other areas.

To reach a patch of rain forest that had yet to be touched by destruction, Sutherlin and his colleagues traveled 10 hours through the night, from Riau to Jambi Province, then another 4 hours by car over horrendous dirt roads, to South Sumatra. From there, they took motorcycles, over winding-ribbon trails, through a desolate oil palm plantation to the edge of the peat lands, and then continued by foot, “on a rough trail along a canal dug by loggers to remove logs from the forest.” Sutherlin was thrilled when they arrived at the forest edge, sweaty and exhausted, to finally see some tall trees still standing. Monkeys howled in the distance. An electric blue butterfly swirled around his head. And spider-hunters, dollarbirds, and bulbuls circled overhead, flitting in and out of view. “Then, as if on cue,” he says, “a chainsaw began to roar just out of sight, followed quickly by the terrible sound of trees crashing through trees to the ground.”

“Sustainable palm is the key to protecting our biodiversity, and our heritage.”

—Raviga Sambanthamurthi.

Virtually all of the forest’s inhabitants are facing annihilation. “The remaining populations of endemic Sumatran rhinos are widely considered to be the living dead,” says Sutherlin. “Their habitat is too sparse, too fragmented and too disturbed, their numbers too few.”