Human impact is the main threat to species worldwide.

Conservation biology is the science of preserving biodiversity. Conservation biologists focus on protecting individual species and maintaining or restoring entire ecosystems. That means they also work intently to understand the threats facing species and ecosystems. Today those threats are legion. As has been detailed in numerous chapters throughout this book, we humans are changing the environment with unprecedented speed—so much so that many populations cannot keep up. We’re clearing more land and building more roads to access more natural resources than ever before. And we’re killing off an alarming number of plants and animals in the process. The details for any given species may differ, but the basic story is often the same: As more and more individuals die off, the genetic diversity of that species dwindles, and the population as a whole becomes increasingly vulnerable to extinction.

conservation biology

The science concerned with preserving biodiversity.

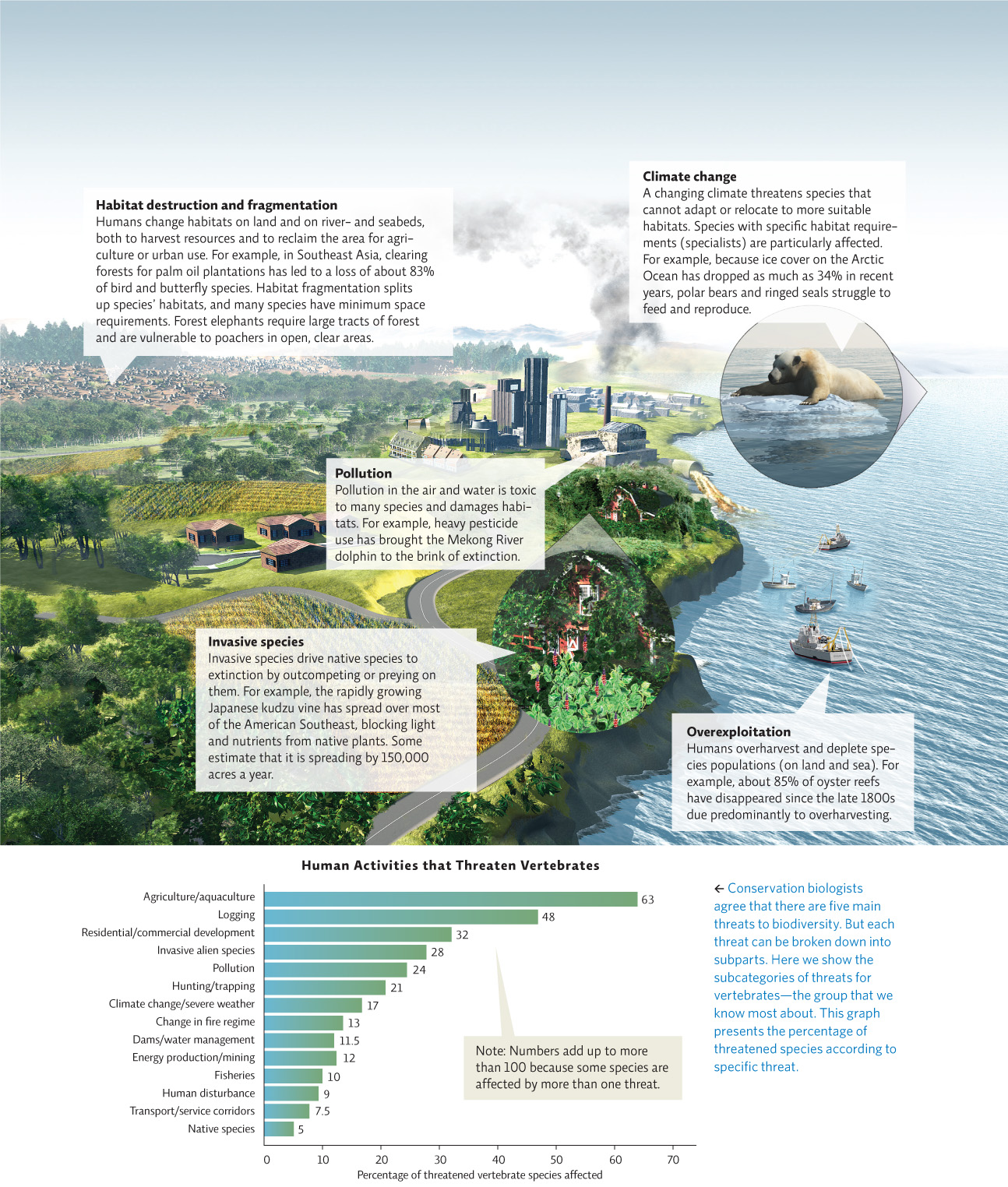

In general, conservation biologists agree that biodiversity the world over faces five main threats—threats tied to an expanding human population and increasing levels of affluence: overexploitation, pollution, climate change, the introduction of invasive species, and (the number-one cause) habitat destruction and fragmentation.

KEY CONCEPT 13.1

Habitat destruction is the biggest threat to species today. Other threats include invasive species, overexploitation, pollution, and climate change.

In recent decades, despite a rash of international attention to the problems of biodiversity loss, each of these factors has gotten worse. Overfishing has claimed some 85% of oyster reefs and as much as 90% of the world’s populations of large predatory fish like tuna and cod (see LaunchPad Chapter 31); pesticides and mercury pollution have all but killed off the Mekong River dolphin; and climate change is threatening to bring the iconic polar bear in the Arctic Circle, not to mention many other species around the world, to disastrous ends. Meanwhile, invasive species are running amok from Alabama to Zimbabwe, thanks to intentional and accidental introductions and human travel around the globe. And habitat fragmentation is isolating populations and limiting their ability to migrate or disperse to new areas. It is also making commercially valuable wildlife— not only elephants with their ivory tusks but also tigers prized for their vibrant skins and rhinos whose horns are used in traditional Chinese medicine—more vulnerable than ever to human predation. INFOGRAPHIC 13.1

Which categories on this graph represent habitat destruction/fragmentation? Does this data support the claim that habitat destruction/fragmentation is the leading cause of species endangerment?

The categories that probably impact species through habitat destruction or fragmentation are: agriculture/aquaculture, logging, residential/commercial development, dams/water management, energy production/mining, and transport/service corridors. This does support the claim that habitat destruction and fragmentation is the leading cause of species endangerment.

KEY CONCEPT 13.2

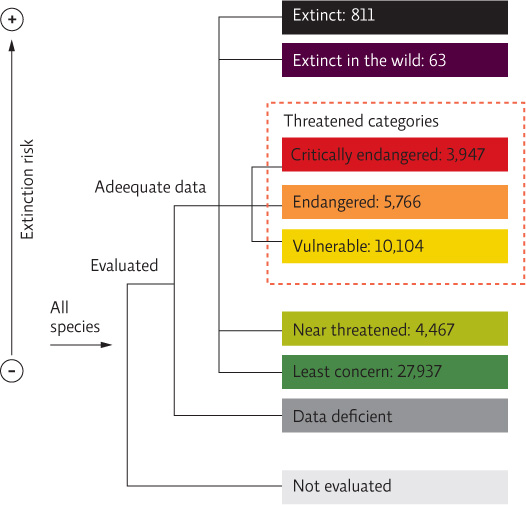

Though most species have yet to be assessed, those that have been are assigned a conservation designation ranging from least concern to extinct.

To bring attention to the problem of threatened species—those that are at risk for extinction—the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) established the Red List of Threatened Species in 1963. The “Red List,” as it is called, uses a series of designations to classify the seriousness of threat to a given species. Species are added to the list when they’re at risk of becoming endangered, and they’re removed when their status improves. The United States as a whole, its individual states, and other countries maintain their own lists of threatened species, using the same designations. INFOGRAPHIC 13.2

threatened species

Species that are at risk for extinction; various threat levels have been identified, ranging from “least concern” to “extinct.”

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) maintains the Red List of Threatened Species, which identifies the conservation status of species worldwide, a process that helps conservationists focus efforts on the species most at risk. Status categories reflect extinction risk and range from extinct to least concern; numbers shown here indicate the number of species in that category as of October 2012.

Look back at Infographic 12.1 to find the total number of named species to date. What percentage of named species have not received a designation (data deficient or not evaluated)?

IG 12.1 tells us there are 1.8 million named species. According to IG 13.2, 53,095 species have conservation designations. That leaves 1,746,905 species that fall into the categories of data deficient or not evaluated; this is 97% of the total. We have only assigned conservation designations to 3% of all known species!

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, one-third of all the plants and animals on Earth are now at risk of going extinct. And if we aren’t worried about that, we should be. “Biodiversity…provide[s] a wide range of services to human societies,” the WCS report’s authors write. “Its continued loss, therefore, has major implications for current and future human well-being.”

To avert the worst of those implications, we must figure out how best to preserve the biodiversity that’s left. And to do that, we must first learn as much as possible about the ecosystems in question: What are the key requirements of its resident species? Are those requirements being met? If not, why not, and what other species are being threatened as a result? For conservation biologists working to save the forest elephants of Africa, answering those questions means, literally, following a trail of poop.