Conservation plans should consider the needs of local human communities.

In Botswana’s forests, peace seems to reign. Elephants, gathered in a clearing, play and groom and engage in all sorts of histrionics. According to Evans, the country boasts the largest population of forest elephants on the continent. There are several reasons for this success: For one thing, the human population is much lower here than it is in countries like Kenya and Gabon, where poaching is epidemic. For another, Botswana’s president has “led from the top,” Evans says. “He’s really made conservation a priority and that helps a great deal.” But the main reason Botswana’s forest elephants are doing so well is that the country’s economy has come to rely on them. It turns out that ecotourism—low-impact travel to natural areas that contributes to the protection of the environment—is a big and thriving industry: Tourists will pay good money to see wildlife and well-preserved wild areas, especially if they know their money is helping conservation efforts. “The people of Botswana have made a very proactive decision,” Evans says. “For their own long-term survival, they see wildlife as a crucial sustainable resource.”

ecotourism

Low-impact travel to natural areas that contributes to the protection of the environment and respects the local people.

KEY CONCEPT 13.8

Successful conservation efforts consider the needs of people who live in the area. Ecotourism and debt-for-nature swaps can provide funding and incentives to protect natural areas; in the process, they benefit local communities.

Therein lies the key: For conservation programs to work, they must protect not only the species in question but also the humans who share its habitat.

A 2009 drought in Kenya, for example—one of the worst droughts in living memory—caused the region’s tribes to lose many of their cows and crops; meanwhile, the price of ivory soared. Brokers just across the Tanzania border were paying around $20 a pound at the time for raw ivory—a deal too good for any starving family to ignore. The bushmeat trade in central Africa offers another example. The loss of agricultural land to environmental degradation and armed conflict has driven more area residents into natural areas to kill wild animals for meat, which in turn diminishes wildlife, increases access to the area, and spreads zoonotic diseases (see Chapter 5) as more people come into contact with wild animals. Steps to improve agriculture, increase access to nutritious food, and resolve political disputes would do more to mitigate these problems than any law prohibiting bushmeat trade.

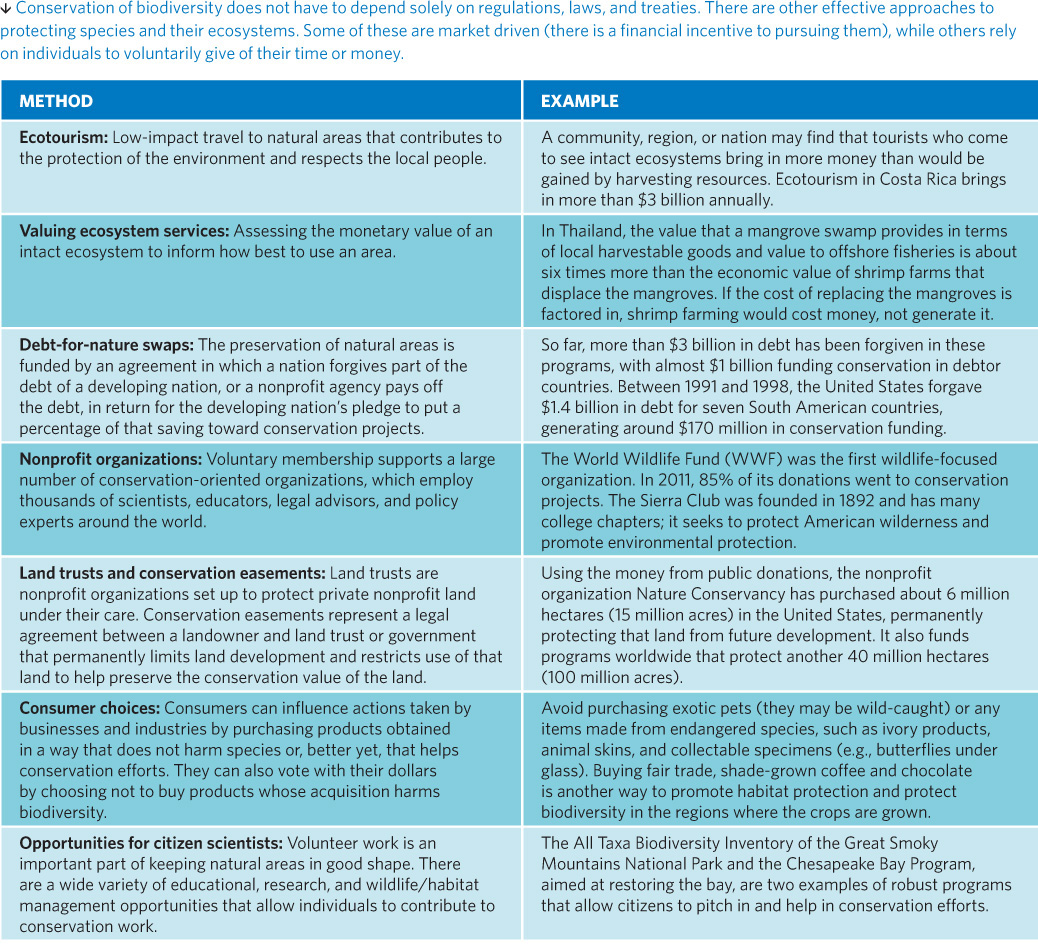

Ecotourism is not the only means to such ends. Debt-for-nature swaps—in which a wealthy nation forgives part of a developing nation’s debt, in return for which the developing nation pledges to protect certain ecosystems—are another way to appeal to the needs of those living nearest the species and ecosystems that are so embattled. (So far, almost $3 billion in debt has been forgiven, and tens, if not hundreds, of millions of acres of wilderness have been preserved through such programs.) Nonprofit organizations have also been major players in conserving species and their habitats. TABLE 13.2

debt-for-nature-swaps

Arrangements in which a wealthy nation forgives the debt of a developing nation in return for a pledge to protect natural areas in that developing nation.

Would you be willing to participate in citizen science projects? If so, what kind of activities would appeal to you?

Answers will vary; this is a good class discussion question.

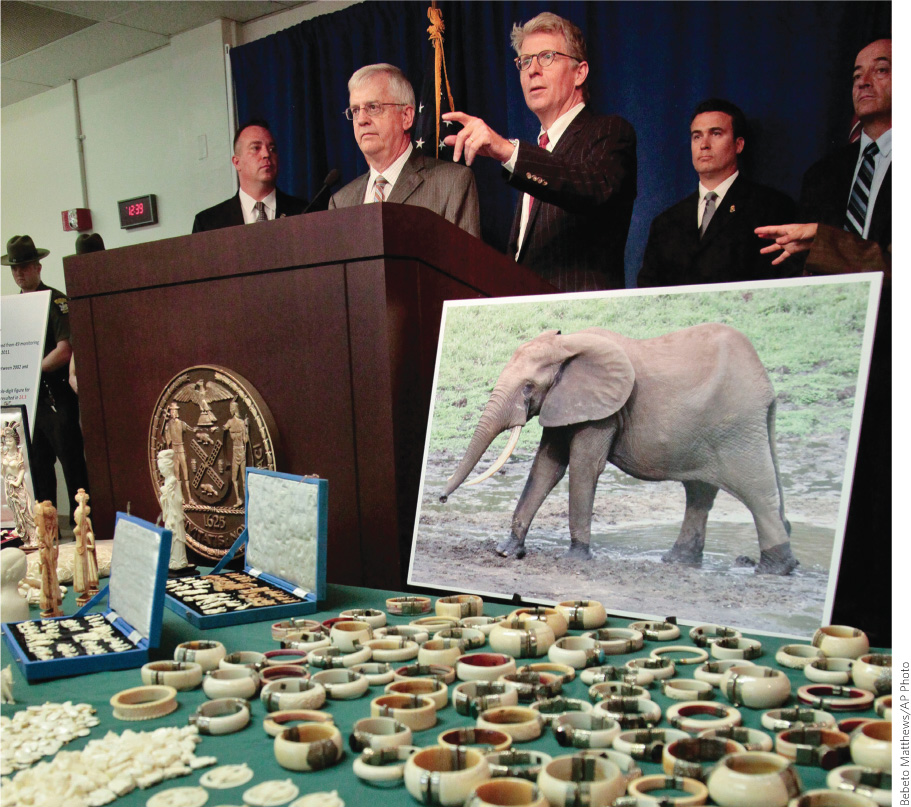

Consumers also play a major role. The first step is to become informed about the threats to species and the consumer choices that help protect biodiversity. For example, some actions harm endangered species (such as buying wild-caught tropical birds or fish, or ivory products), whereas other choices support the sustainable use of natural areas, like buying sustainably grown coffee and palm oil products (see Chapter 12) or sustainably harvested fish (see LaunchPad Chapter 31). Buying or using fewer resources (from gasoline to sunglasses to sneakers) means less impact on the natural areas (and their resident species) from which the resources are extracted or made. Finally, reducing one’s contribution to climate change will reduce this threat to Earth’s biodiversity (see Chapter 21.)

For his money, Blake says better enforcement of existing laws and a marketplace that reflects the true costs of natural resources would go a long way toward curbing poaching. “Bad environmental companies need to be penalized and good ones rewarded,” he says. Yes, this will drive up the cost of certain goods—low prices cannot be maintained if companies have to invest in good road planning, stop poaching, and engage in other environmentally and socially friendly practices. But, as with any other natural resource—from water to timber to coal and oil—higher prices might be the key to better conservation and lower overall costs in the long run.

KEY CONCEPT 13.9

The average person can help protect biodiversity by making wise consumer choices that support the sustainable use of natural areas and that avoid contributing to any of the main causes of species endangerment.

However, Evans says, education may be the most crucial element of all. “We want the communities living in close proximity to elephants to understand that they provide crucial ecosystem services,” she says. “We also want people in developed countries to understand that even if they never set foot on the African continent, or see an elephant up close, their decisions have a direct impact on these ecosystems.”

Because in the end, it’s demand from these countries—not only for ivory products but for timber and other resources—that’s driving and facilitating the trade.

Ultimately, then, the story of the forest elephant ends not in a shrinking African forest, or even in a Chinese port city, but much closer to home: in a jewelry shop in a bustling Manhattan neighborhood. That’s where federal agents recently discovered $2 million worth of illegal ivory. In 2012, the shop’s owners pled guilty to selling ivory without permits; under plea bargain, they agreed to forfeit the products and to pay $55,000 in donations to the WCS for use in elephant conservation and anti-poaching efforts. It was a rare victory for conservationists, one that underscored a crucial point for Wasser, Evans, Blake, and others. “It’s a global problem that requires very local solutions,” Evans says. In the end, preserving biodiversity—even in the jungles of Africa—begins right here at home.

Select References:

Baillie, J. E. M, et al. (2010). Evolution Lost: Status and Trends of the World’s Vertebrates. London: Zoological Society of London.

Blake, S., et al. (2007). Forest elephant crisis in the Congo Basin. PLoS Biology, 5: e111. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050111

CITES. (2014). Elephant Conservation, Illegal Killing and Ivory Trade: Report to the Standing Committee of CITES. Sixty-fifth meeting of the Standing Committee. Geneva, Switzerland, July 7–11, 2014.

Stokes, E. J., et al. (2010). Monitoring great ape and elephant abundance at large spatial scales: Measuring effectiveness of a conservation landscape. PLoS ONE, 5: e10294. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010294

United Nations Environment Programme. (2012). Global Environmental Outlook—5 Report, http://unep.org/geo/pdfs/geo5/GEO5_report_full_en.pdf.

Wasser, S. K., et al. (2008). Combating the illegal trade in African elephant ivory with DNA forensics. Conservation Biology, 22: 1065–1071.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

A recent study estimates that nearly 9 million different species are found on Earth. With such a stunning amount of biodiversity, it is hard to imagine that we could possibly be in danger of losing a significant number of these species to extinction. Yet the extinction rates will continue to grow if we do not consider serious changes.

Individual Steps

•Gain an appreciation for the tremendous diversity we have by watching a documentary of an ecosystem far away from you. Make a list of all the species featured in the documentary and then check their status at www.iucnredlist.org.

•Avoid purchasing any pets that are listed as endangered species, even those bred in captivity, as this can increase the threat to the species in the wild. If you do choose to buy an exotic pet that is not an endangered species, request certification that it is captive bred.

•Consider contributing to an organization that works to protect species or their habitat; check out options at www.fws.gov/endangered/what-we-do/ngo-programs.html.

Group Action

•Identify county and state parks and preserves around you. Find out what specific actions they take to maintain the biodiversity of the ecosystems there, such as removing invasive species and cultivating native ones. Form a volunteer group to assist in these efforts.

•Discover which endangered species live in your state at www.fws.gov/endangered/. Make flyers and posters with images and information about these species and their habitats. Share them around your school or community.

Policy Change

•The goal of the U.S. Endangered Species Act is the protection of species diversity. To learn more about current challenges and updates to the program, visit www.epa.gov/espp.