Untreated wastewater can contaminate freshwater sources and is a serious health risk worldwide.

Jack Skinner is a medical doctor and lifelong surfer based in Orange County, whose house in Newport Beach is supplied with water from the county’s wells. His second home is in Laguna Beach, surrounded by water; in the morning, he and his wife would watch from their oceanview apartment as the Sun would light up a pole stationed about a mile offshore, marking the spot where a nearby sewer treatment plant discharged its effluent. “Every morning when we got up, we would see that marker.” In the early 1980s, he began experiencing eye infections while distance swimming along the coast. He decided to learn more about the impact of releasing wastewater into the ocean and how the wastewater was being treated.

effluent

Wastewater discharged into the environment.

Sewage can carry pathogens like viruses and disease-causing bacteria, and surfers get exposed to these when they surf in sewage outflow that is untreated. Public health officials monitor drinking and recreational waters for the presence of coliform bacteria. Since many coliforms are intestinal bacteria, their presence could indicate fecal contamination of the water.

coliform bacteria

Bacteria often found in the intestinal tract of animals; monitored to look for fecal contamination of water.

Over the years, Skinner had become a self-proclaimed “troublemaker,” making sure that wastewater was highly treated before being discharged into the Pacific Ocean, and speaking publicly about water pollution.

One day, the Orange County Sanitation District (OCSD) called Skinner and asked him to come in for a meeting. The OCSD wanted to consult with him about a massive new project that that would need the support of the community in order to succeed. What people at the meeting said made Skinner very concerned.

In the mid-1990s, Orange County water sanitation engineers and hydrologists found that they faced a problem of water scarcity and, at times, the opposite problem—too much water.

As an increasing number of people moved to the region, they used more water, creating excess wastewater. The OCSD already operated an 8-kilometer (5-mile) “outfall,” or underground pipeline that takes treated sewage water past California’s beaches and out to the Pacific Ocean. The OCSD also had another 1.6-kilometer (1-mile) long outfall to the Santa Ana River, but it was not enough to handle heavy rainfall, which could wash sewage through and out of a facility before it could be adequately treated. About 375 million liters (100 million gallons) a day of partially treated sewage water was already flooding the river. Nearly five times that amount would reach the river during a major storm. The county was considering building another pipeline to carry excess water to the Pacific Ocean.

But such an endeavor would be incredibly expensive. So the OCSD considered a project that would solve both the problem of too much wastewater and too little freshwater. It decided to expand the existing system that used treated wastewater to protect groundwater from infiltration by the ocean. But folks at the agency knew they would face community opposition.

Since the 1970s, the county had been pumping only small amounts of treated wastewater into the ground—about 19 million liters (5 million gallons) per day, and only at the coasts. This new project would expand that amount to 260 million liters (70 million gallons) per day, and it would take place not just at the seawater barrier. The actual amount of treated wastewater that would make its way into people’s homes would vary but would ultimately average 15% in north and central Orange County, says Deshmukh. “All of a sudden, it became a significant component of the water supply.”

Once the project was conceived, OCSD began intensive community outreach, such as giving presentations in front of community groups about water scarcity and the need for new sources and placing representatives at big events. “Any chance we got we would talk about it,” says Deshmukh. Part of the multiyear initiative included outreach to community leaders, such as Skinner.

When Skinner initially learned about the project, and the fact that OCSD had been doing a smaller version at the coast for decades, he was uneasy. “Since the late 1970s, my family had unknowingly been drinking that water,” Skinner says. “I thought of my daughter, who lives in the area. I thought about my grandson, Robbie. He would be drinking the water, and is probably right now. I wanted to be sure it was safe.”

KEY CONCEPT 14.6

Wastewater can be decontaminated using high-tech methods that use advanced filtration and harsh chemicals or low-tech methods that mimic the way wetlands purify water.

So Skinner set about learning how the wastewater would be treated. The state health department appointed him to serve on a state committee that would review the treatment process for the recycled wastewater, and Skinner began speaking with experts about the techniques.

Wastewater is simply water that has been used and disposed of (by individuals, businesses, or industry), and it can contain a wide variety of contaminants, from food waste to sewage to chemical pollutants. Prior to the 20th century, most wastewater in the United States (and elsewhere) was simply released to the environment, untreated. As populations swelled and wastewater amounts increased, this untreated sewage became a major source of contamination, harming the environment and human populations. Today, before it can be safely released into the environment, it must be cleaned, or “treated.”

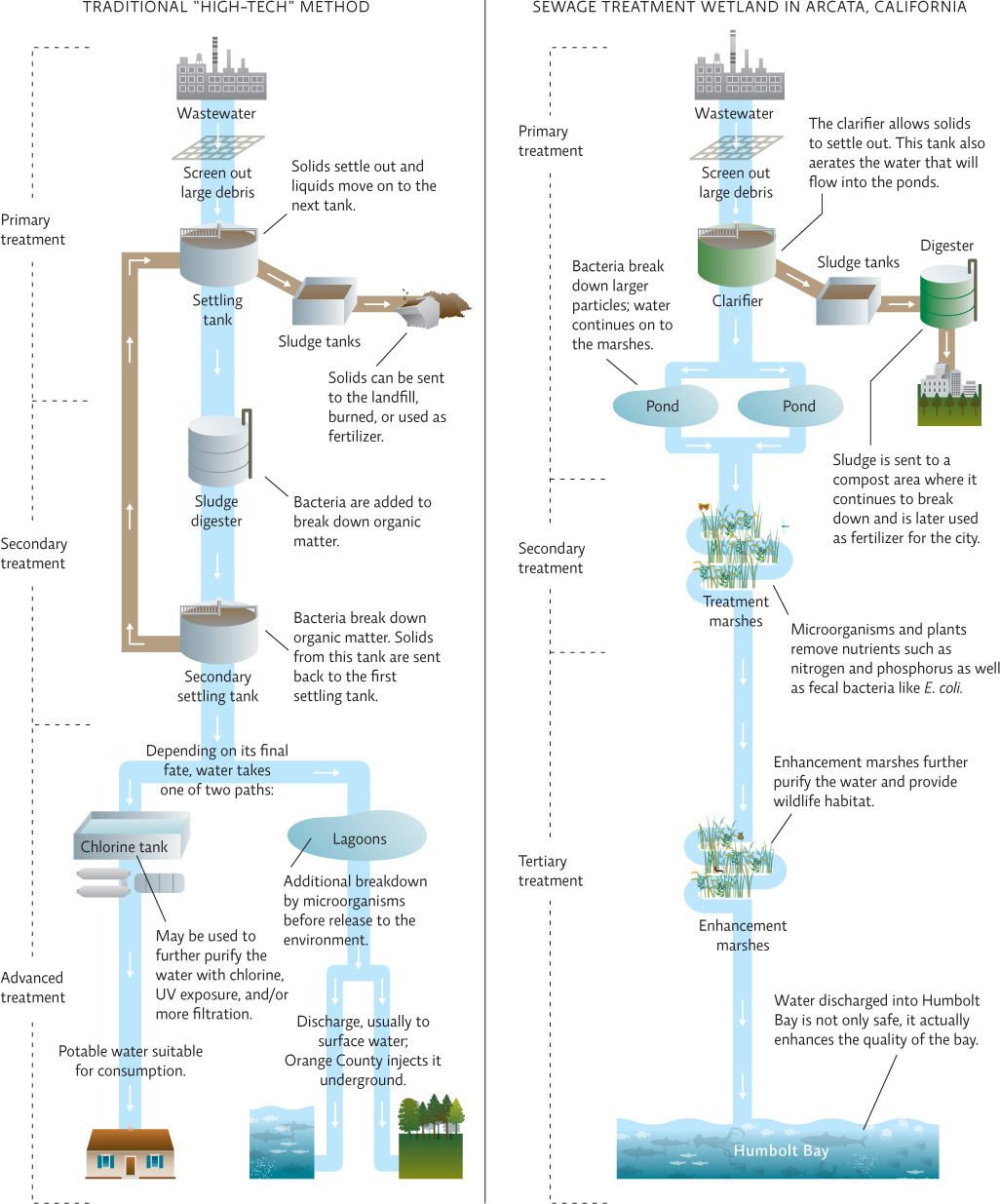

Typically, wastewater treatment includes initial steps that filter the water then send it to settling tanks where much of the remaining suspended solids sink to the bottom. The water continues on to other tanks where bacteria digest much of the remaining organic matter. At this point it may be clean enough to release into the environment.

wastewater treatment

The process of removing contaminants from wastewater to make it safe enough to release into the environment.

Skinner learned that the first step of the cleaning process used by Orange County consisted of microfiltration, in which microscopic, strawlike fibers, 1/300 the diameter of a human hair, filter out many suspended solids, bacteria, and other viruses because only water can pass through the center of the fibers. Then, to render wastewater potable—safe for humans to drink—engineers would perform a crucial step known as reverse osmosis. During this process, they use pressure to force water through a plastic membrane. The pores of this membrane are so tight, explains Deshmukh, that salt and other contaminants (such as pharmaceutical drugs and toxic chemicals) do not pass through, but water does. After reverse osmosis, the water is exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, which kills any remaining viruses and bacteria. At completion, the final product is cleaner than state and federal regulations require.

potable

Clean enough for consumption.

Another California community, Arcata, tackled its water purification problems in a different way. Rather than construct a typical wastewater treatment facility to handle sewage that had been contaminating nearby Humboldt Bay, they repurposed a retired landfill near the coast by converting it to a wetland—an ecosystem that is permanently or seasonally flooded. A slow river meanders through the wetland where organisms there purify it; to them, it’s not “sewage,” it’s food. The Arcata facility depends on nature to perform the job of water purification. The water discharged into the ocean is very clean, and the health of the bay ecosystem has improved. But while the Arcata facility addresses the need to decontaminate sewage, it does not take the extra steps to produce potable water like Orange County’s GWRS. INFOGRAPHIC 14.5

wetland

An ecosystem that is permanently or seasonally flooded.

Sewage must be treated before it can be safely released to the environment. Most communities use chemical- and energy-intensive high-tech methods, but systems that mimic nature can also effectively purify water.

Compare the traditional high-tech method of wastewater purification to the wetland system for wastewater purification. What do they have in common? How are they different?

They both initially filter the wastewater and both use bacteria to help digest contaminants in wastewater. Some high-tech wastewater purification systems may even use some outdoor, environmental waters (such as ponds or lagoons) for part of the contaminant breakdown. The high-tech system however, uses chemical treatment to further kill organisms that might be in the wastewater and produce water that is potable. Wetland wastewater purification systems can produce water safe to release into the environment (like the high-tech method does) but it would take further treatment to produce potable water (by U.S. standards).

The GWRS went online in January 2008, and now Orange County’s water district taps its artificially replenished groundwater to deliver clean freshwater to people for drinking, irrigation, and other uses. As of spring 2014, it had recycled more than 5 trillion liters (136 billion gallons) of water. Every day, approximately 260 million liters (70 million gallons) of recycled water are pumped into wells or percolation basins in Anaheim, where sand and gravel naturally purify the water further as it trickles down into the region’s aquifers—enough to meet the needs of nearly 600,000 residents.