Conservation is an important “source” of water.

The GWRS project was expensive: The total price tag to build the system came to about $481 million from federal, state, and local funding. It is currently being expanded to create another 114 million liters (30 million gallons) per day.

An easier and cheaper way to maintain water supplies is simply not to waste so much. For example, water-saving irrigation methods limit loss to evaporation and runoff, thus significantly reducing the water that is used—by as much as half, according to Tess Russo of the Columbia Water Center at Columbia University. This has the added advantages of protecting surface waters and of preventing soil salinization (the buildup of salt as water evaporates), a common problem in dry climates. Choosing to plant crops more suited to the environment and water availability will also decrease agricultural water use. Many industrial processes are now designed to reuse water rather than discharge it into the environment.

KEY CONCEPT 14.8

Conservation can effectively address scarcity and includes the use of water-saving technologies, behavioral changes that decrease water use, and consumer choices that minimize our water footprint.

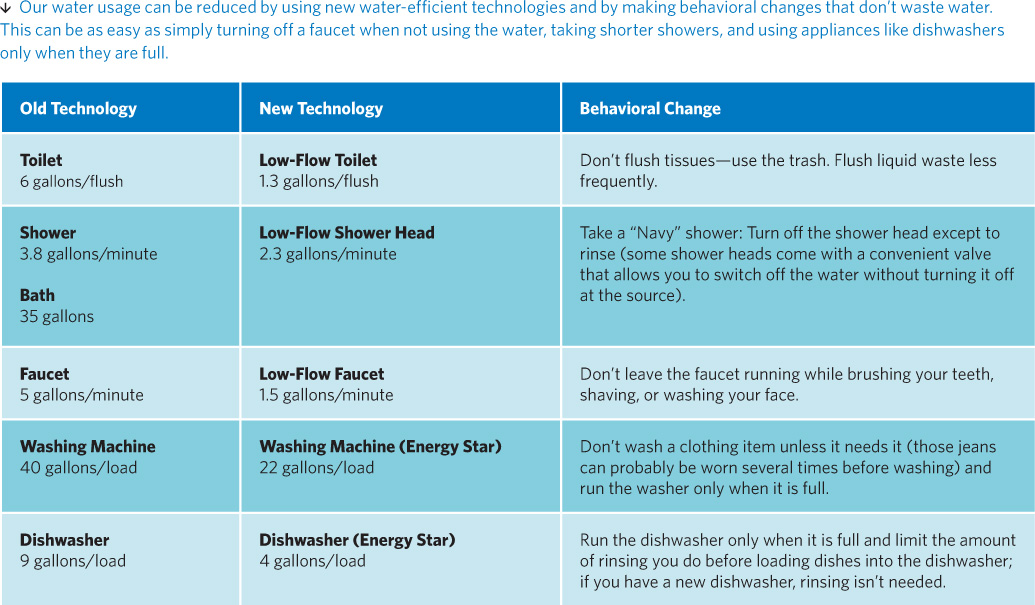

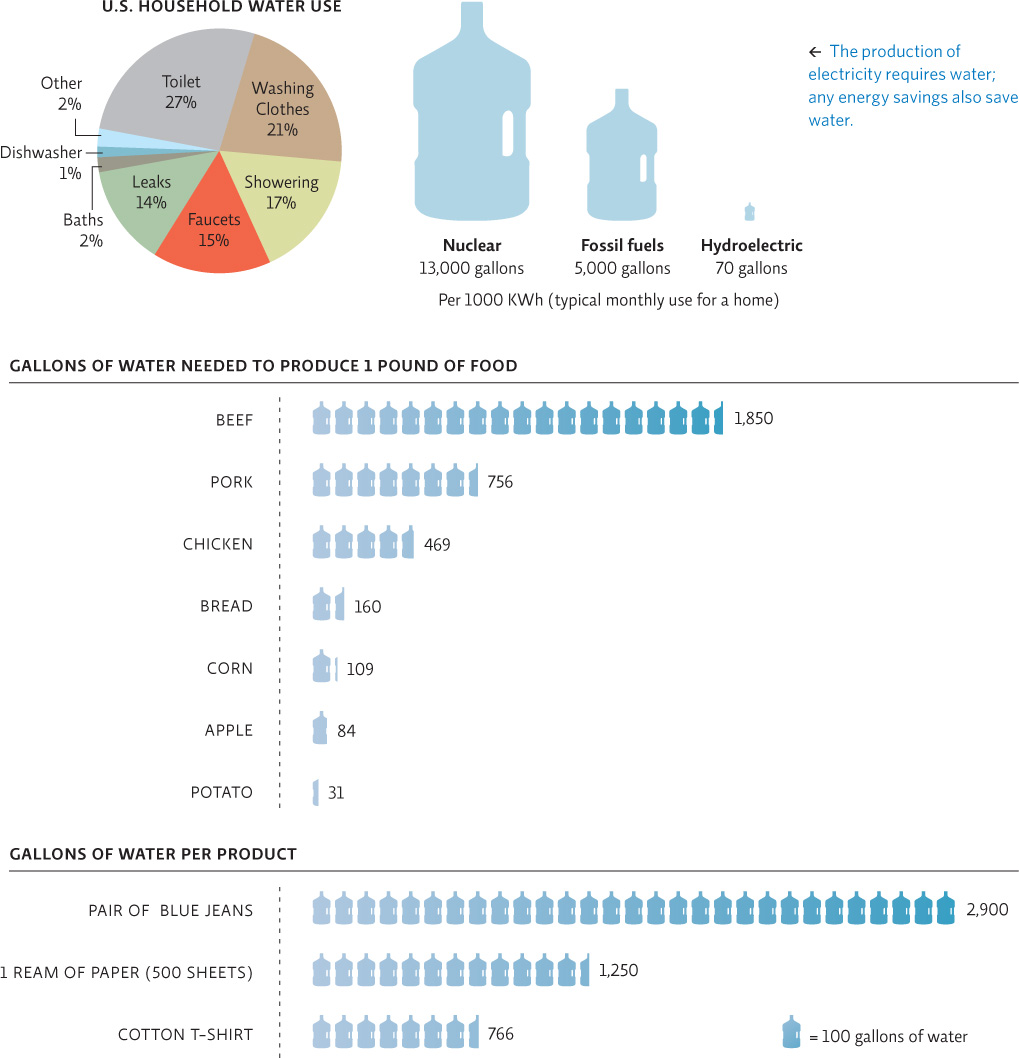

The average U.S. citizen uses about 300 liters (80 gallons) of water per day in the home. Small individual changes in the household can save a lot of that water. But it is important to remember that our personal use of water is not limited to direct use of water from the tap. Water is also used on our behalf by industry to produce the products and energy that we consume (indirect use). This brings the average daily use of water up to 7,500 liters (2,000 gallons) per person in the United States. Reducing our use of resources and making wiser consumer choices with the purchases we make can reduce our water footprint. TABLE 14.1 and INFOGRAPHIC 14.6

water footprint

The water appropriated by industry to produce products or energy; this includes the water actually used and water that is polluted in the production process.

Estimate how long your typical shower lasts and then calculate how much water you would use over the course of a year if you used a traditional, 3.8-gallon/minute shower head. Do the same calculation for the low-flow shower head. How many gallons per year would you save by switching to a low-flow shower head? Compared to the water used in a typical shower using a traditional shower head, how much would you save in a year if you reduced the duration of your shower by half and used a low-flow shower head?

Answers will vary based on the length of the typical shower and the number of showers taken per year. A 10 minute shower with a 3.8 gallon/minute shower head uses 38 gallons of water; a daily shower over a year’s time would consume almost 14,000 gallons (13,870 gallons). Switching to a low-flow shower head at 2.3 gallons/minute uses 23 gallons for a 10 minute shower which equates to 8,395 gallons per year. A year’s worth of shorter showers (5 minutes in this case) with the low-flow shower head would save 9,522.5 gallons compared to the longer shower using the high-flow shower head.

Understanding how we use water on a daily basis helps us make decisions about ways to save water. Much of our water usage can be reduced by buying less stuff and by choosing products with lower water footprints for those things we do choose to purchase. Using less energy through conservation and using more energy-efficient products will also reduce our water footprint.

How much water could be saved in 1 week if a person who normally eats ¼ pound of beef daily made a change to eat ¼ pound of beef twice a week and ¼ pound of chicken the other 5 days of the week? How much water would be saved in a year?

Eating ¼ pound of beef for 7 days requires 3,237.5 gallons of water (0.25 x 7 = 1.75 pounds of beef per week; 1.75 x 1,850 gallons = 3,237.5 gallons). Eating beef for 2 days (½ pound of beef = 925 gallons of water) and chicken for 5 days (1.25 pounds of chicken x 469 gallons = 586.25 gallons) uses a total of 1,511.25 gallons of water. This saves a total of 1,726.25 gallons of water over one week’s time (3,237.5 - 1,511.25 = 1,726.25). Over a year’s time, this saves 89,765 gallons of water.

In the meantime, supplementing potable water supplies with recycled water is an innovative way to help ameliorate ongoing water issues, says Channah Rock, a water-quality specialist and assistant professor at the University of Arizona. It’s rare to find initiatives like Orange County’s, she says, but several communities—in Arizona, California, Nevada, and Florida, for instance—are reusing recycled water for nonpotable use, such as for irrigating landscapes and crops, filling fountains and fire hydrants, and flushing toilets. Communities are trying to “match the quality of water with the right use of water,” she says. Since people are prohibited from drinking the water that is used for irrigation, for example, says Rock, it’s not necessary to subject that water to the same advanced treatment processes as are used for potable water.

Public perception of recycled water projects actually varies, says Rock, depending on how familiar or confident people are with the treatment process and how plagued their community is by water-scarcity issues. In Arizona, which has regions affected by drought, a recent statewide survey found that Arizona residents generally supported most potential uses of recycled water and felt that it was very important that their community use recycled water to help meet its water needs. To many people, she says, what matters is that the water ultimately meets regulatory standards designed to protect public health. In fact, Rock says, the “toilet to tap” phrase is incredibly misleading because it leaves out the testing, treatment, and scrutiny that take place in between.

One California community may be taking the toilet to tap approach even further. An ambitious project in San Diego would send highly purified wastewater directly to the tap rather than injecting it into a larger water source such as an aquifer or reservoir; this project is not yet approved (by residents or the state of California).

The GWRS has received many accolades, including the prestigious 2008 Stockholm Industry Water Award. In 2010, just 10 years after Deshmukh finished graduate school, his work was profiled in National Geographic. It’s an achievement that fills Deshmukh with pride. “This is water that’s normally just wasted in the ocean. For the first time, it was being added to the water basin, cleaner and at a higher quantity than we’d done before.”

Once Skinner learned how the water would be treated, spoke to scientists about the effectiveness of the treatment process, and learned that the project would have continuous oversight, he was reassured. “I feel they have successfully addressed my concerns,” he says. Skinner and Deshmukh even worked together to create videos describing the project. Today, Skinner, his wife, daughter, and grandson consume the recycled water. “I think it’s safe for my family to drink.”

Select References:

Heffernan, O. (2014). Bottoms up. Scientific American, 311(1): 69-75.

Hoekstra, A., & A. Chapagain. (2007). Water footprints of nations: Water use by people as a function of their consumption pattern. Water Resources Management, 21(1): 35–48.

United Nations World Water Assessment Programme. (2014). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2014: Water and Energy. Paris: UNESCO.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Regardless of whether our water comes from an aquifer or a local reservoir, we can make those water sources last longer by taking steps to use our water as efficiently as possible.

Individual Steps

•If you have a smartphone, download a water usage tracking app. Once you have a baseline, try to reduce it by 10%.

•Time your shower and try to reduce it by 1 to 2 minutes.

•Have a container by the sink or shower to catch water while it warms up; make sure not to get soap in it. Use this water for watering plants both inside and out.

Group Action

•Install a rain barrel at home. Rain barrels allow people to use the rain that falls on the roof of a building to water plants as opposed to letting it run off into the storm drain. If you live in a dorm or an apartment, see if you can get permission to have a rain barrel installed.

Policy Change

•Do you know where your water comes from? Talk to a city representative to find out where your water comes from and what steps are being taken to make sure it lasts as long as possible.

•Encourage local policy makers to ban the watering of lawns or restrict the use of water for landscaping to certain days of the week.