World hunger and malnutrition are decreasing but are still unacceptably high.

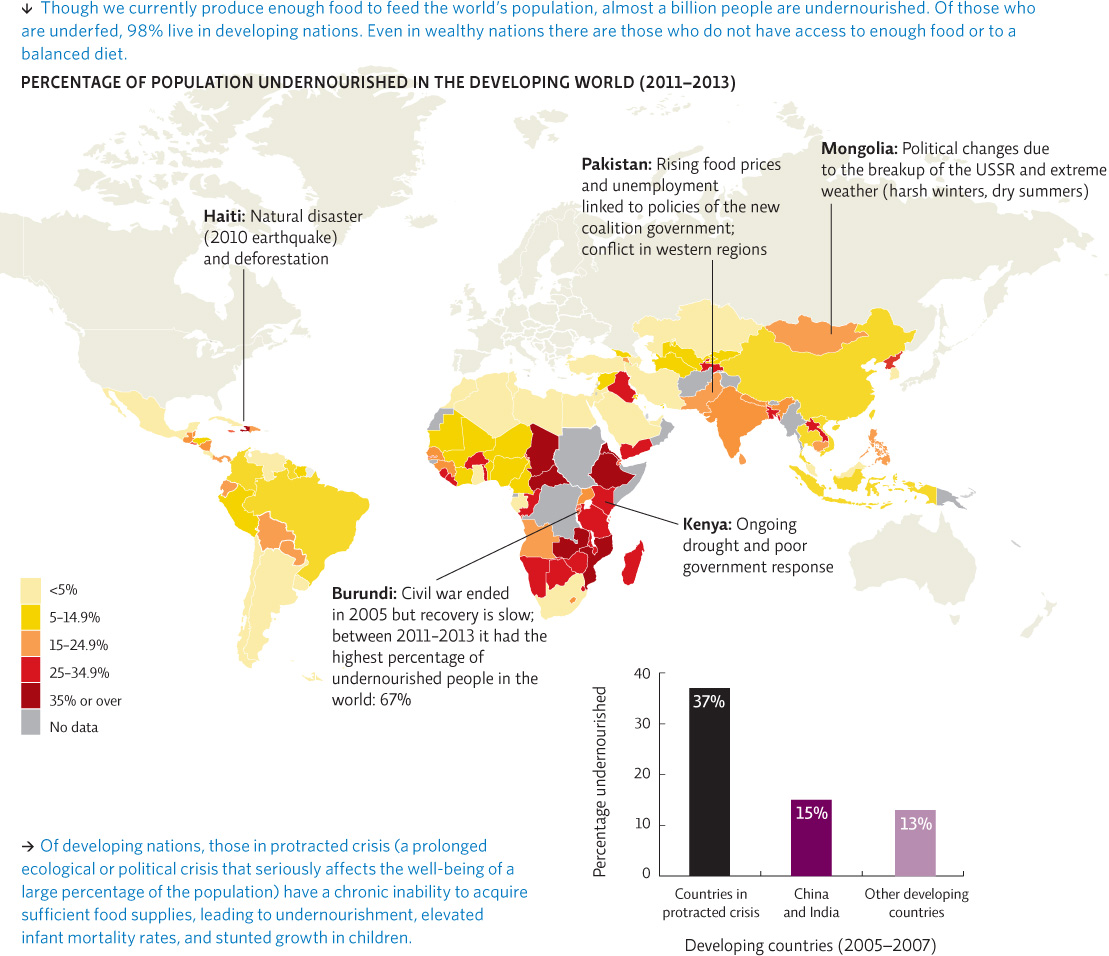

While global food prices have stabilized since the 2008 riots, and grain reserves are currently well stocked, much of the world is still struggling to feed itself. The world currently produces enough food to feed the human population—enough to provide each person with more than 2,800 calories per day, according to a 2011 analysis by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Yet in 2013, the United Nations estimated that 842 million people (about 12% of the global population) suffered from undernutrition—meaning that they did not consume enough calories to meet daily needs. According to the World Food Programme of the United Nations, hunger and poor nutrition is the leading health risk worldwide and causes almost half of all deaths in children under 5 years of age annually. INFOGRAPHIC 16.1

Why do you think so many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have a large percentage of their population that is undernourished, whereas the countries in northern Africa have less than 5% of their population undernourished?

There are probably a variety of reasons – the countries in sub-Saharan Africa may be politically more unstable, suffer from more environmental problems such as drought, or have higher levels of poverty than the countries in northern Africa.

The FAO has set itself the task of eradicating hunger (and extreme poverty along with it). Its goal is to cut the percentage of underfed people around the world in half from the 1990–1992 level by 2015 and to one day achieve total food security. Food security is defined as all people at all times having physical, social, and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food. The FAO’s mission is not just a matter of food quantity but also of improving food quality. A healthy diet contains a variety of foods that provide the proteins, carbohydrates, and fats needed for good health, as well as enough calories to meet daily energy needs. The food that supplies these calories must also supply micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals.

food security

Having physical, social, and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food.

KEY CONCEPT 16.1

Malnutrition is a worldwide problem: Almost 1 billion people don’t take in enough calories and/or nutrients; 1.5 billion consume too many calories.

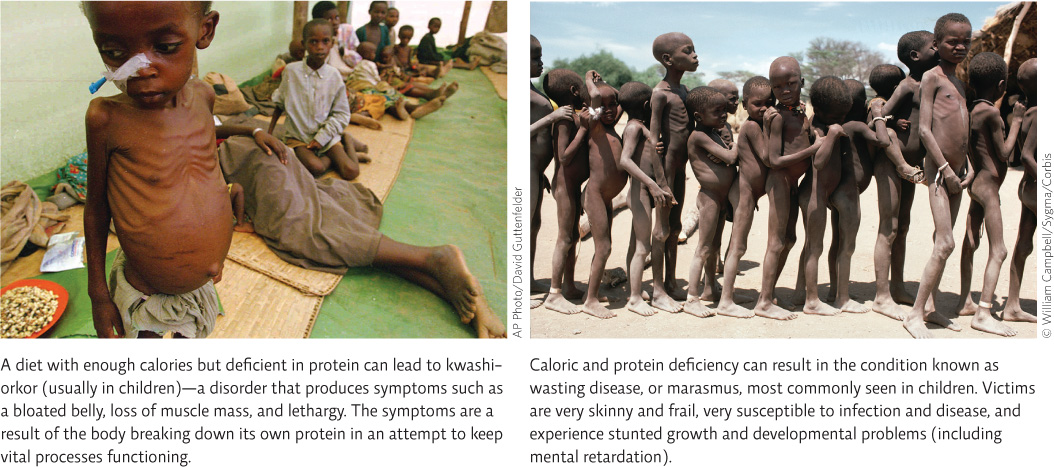

When a person’s diet falls short of these basics—when he or she does not consume enough protein or vitamins—that person is said to be malnourished. Malnutrition can serve as a prelude to a whole host of diseases, from blindness (a result of vitamin A deficiency) and anemia (iron or vitamin B12 deficiency) to wasting (or marasmus) and kwashiorkor. INFOGRAPHIC 16.2

Malnutrition is defined as a state of poor health that results from inadequate or unbalanced food intake. This includes diets that don’t provide enough calories (and thus are nutrient deficient) as well as those that may provide enough (or even too many) calories but are deficient in one or more nutrients.

AP Photo/David Guttenfelder

© William Campbell/Sygma/Corbis

Compare and contrast kwashiorkor and marasmus.

Both diseases result from malnutrition and the inadequate intake of enough essential nutrients. They differ in that with kwashiorkor, there is adequate calorie intake; in marasmus there is not.

malnutrition

A state of poor health that results from inadequate caloric intake (too many or too few calories) or is deficient in one or more nutrients.

Overnutrition, or the consumption of too many calories, is also considered malnutrition. By some estimates, about 1.5 billion people around the world are overnourished and are thus vulnerable to another set of nutrition-related conditions—namely obesity and type 2 diabetes. Contrary to intuition, this is also a problem of the poor. Cheaper foods tend to make us unhealthy. And because those foods are often low in essential nutrients, people who consume too many calories are often just as malnourished as those who consume too few.

Of course, to conquer global hunger, we must grapple with more than just nutrients and calories. Indeed, we must tackle a vast array of problems that lie at the root of the brewing food crisis. Political instability and ecological degradation play significant roles, to be sure. As shown in Infographic 16.1, undernourishment is three times greater in developing nations experiencing a prolonged armed conflict, drought, or natural disaster than it is in countries not in such crises. But there are other contributors, too—namely, social disempowerment and poverty. Even in the poorest countries (or especially in the poorest countries), there are groups of people who have access to food and groups of people who do not. To reach the FAO’s lofty goals, we must first understand why and how that came to be.

And to do that, we must travel back through recent history, to the last time global hunger was the stuff of headlines.