Agricultural advances significantly increased food production in the 20th century.

It was the late 1960s. Global population was soaring; food crops were flatlining in some parts of the developing world and plummeting in others. India especially seemed to be hovering on the brink of a massive famine.

To stave off such catastrophe, the international community had launched the Green Revolution—a coordinated global effort to eliminate hunger by bringing modern agricultural technology to developing countries in Asia. Working across the globe, scientists, farmers, and world leaders introduced India and China to chemical pesticides, sophisticated irrigation systems, synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, and modern farming equipment— technologies that most industrialized nations had already been using for decades. They also introduced some novel technology—namely, new high-yield varieties (HYVS) of staple crops like maize (corn), wheat, and rice. HYVs have been selectively bred to produce more grain than their natural counterparts, usually because they grow faster or larger or are more resistant to crop diseases.

Green Revolution

A plant-breeding program in the mid-1900s that dramatically increased crop yields and paved the way for mechanized, large-scale agriculture.

high-yield varieties (HYVs)

Strains of staple crops selectively bred to be more productive than their natural counterparts.

If all that were not enough, developed countries like the United States also began implementing a litany of agricultural policies—tax breaks, government subsidies, and insurance plans—that encouraged their own farmers to plant crops “fencerow to fencerow” and thus added substantially to the world’s food supply.

In the short term, the effort was a huge success. The combined force of HYVs, existing technology, and new food policies resulted in a 1,000% increase in global food production and a 20% reduction in famine between 1960 and 1990. Today, most experts credit the initiative with the fact that we are now producing enough food to feed every one of the planet’s 7 billion or so mouths.

famine

A severe shortage of food that leads to widespread hunger.

So why are so many people still going hungry?

KEY CONCEPT 16.2

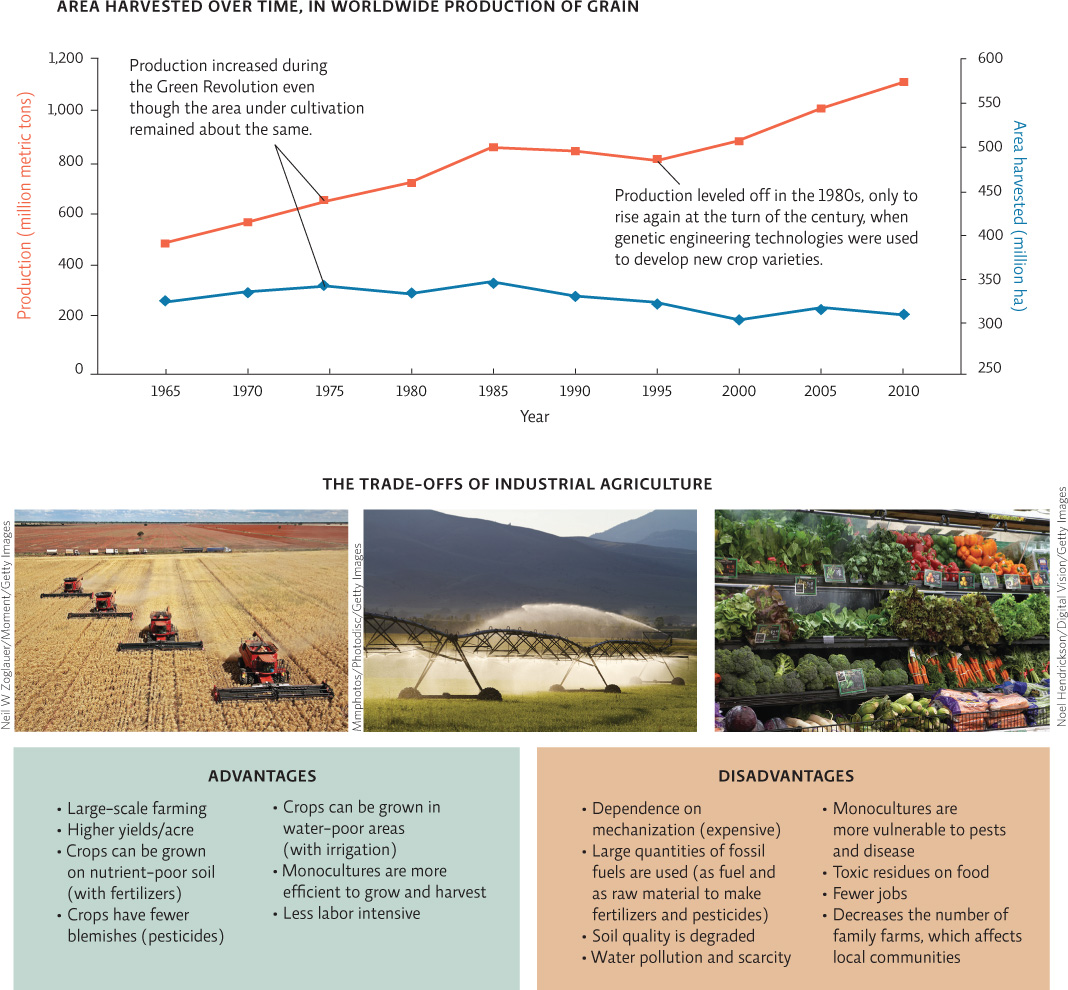

Modern industrial agriculture produces huge amounts of food but leads to ecological and social problems. The Green Revolution exacerbated these problems.

As it turns out, the Green Revolution owes its success to modern industrial agriculture. Though industrial agriculture can be very productive, it has had some unintended consequences. Industrial agriculture is dependent on machinery, as well as synthetic fertilizers (chemicals that boost plant growth beyond what the soil could naturally support) and pesticides (chemicals that protect crops from pests that might harm or consume the crop before harvest). In many cases, mechanized irrigation, drawn from surface water or groundwater supplies, is also used and allows farmers to grow crops that could not be sustained by local rainfall. This mechanization and these chemical farming “inputs” increase efficiency and produce tremendous amounts of food on a large scale. Typically, a single, genetically uniform crop (monoculture) is planted, making it possible for fewer farmers to farm larger tracts of land using heavy equipment like tractors and combine harvesters.

industrial agriculture

Farming methods that rely on technology, synthetic chemical inputs, and economies of scale to increase productivity and profits.

But farming in this fashion produces environmental problems that just get worse over time. For one thing, excessive use of chemical inputs and large-scale monoculture operations have degraded the soil, making it less fertile (and in need of even more fertilizers). It has also contributed to the twin problems of water pollution and water scarcity. Large-scale irrigation can also deplete water supplies; in hot, arid areas, high rates of evaporation can leave a salt residue on soils which impedes plant growth and even renders some soils unusable. Widespread pesticide use is leading to pesticide-resistant pests that are harder to kill, in addition to exposing farm workers and consumers to toxic chemicals. Farm equipment runs on fossil fuels, and even the fertilizers and pesticides are derived from fossil fuel, made from natural gas or petroleum. This requires more fossil fuel extraction, with all its accompanying environmental issues (see Chapters 18 and 19). There are also local social and economic impacts: Fewer farmers on larger farms threaten to make the family farm a thing of the past, impacting entire communities. (For more on industrial farming, see Chapter 17 and LaunchPad Chapter 30).

The Green Revolution also led to a heavy reliance on just a few high-yield varieties of each crop, which has led to a dramatic reduction in agricultural biodiversity. This is no small matter. Without a diverse gene pool, the global food supply is much more vulnerable to pests that can’t be controlled by agrochemicals: When all plants in the field are genetically identical, what kills or damages one will probably kill or damage them all. Moreover, as the old varieties fall out of use—as farmers stop producing and conserving the seeds that have been bred through traditional agriculture over thousands of years—many valuable genetic traits face the possibility of being lost forever. INFOGRAPHIC 16.3

The Green Revolution transformed agriculture into the industrial model we see today. Through the selective breeding of the most productive plants, high-yield varieties of crops were developed that more than doubled production per acre (when grown with inputs like fertilizer and pesticides). This increased food supplies worldwide but brought with it a new set of problems.

Neil W Zoglauer/Moment/Getty Images

Mmphotos/Photodisc/Getty Images

Noel Hendrickson/Digital Vision/Getty Images

Which of the advantages of industrial agriculture do you feel is its greatest strength? Why? Which of the disadvantages of industrial agriculture worries you the most? Why?

Answers will vary but should be supported with evidence.

No one can dispute the fact that the Green Revolution fed, and continues to feed, a lot of people. Unfortunately, not everyone has benefited from this agricultural transformation. Africa, a continent plagued by hunger and largely bypassed by the Green Revolution, has nonetheless fallen prey to a different set of the Green Revolution’s unintended consequences: a lack of food self-sufficiency (the ability of an individual nation to grow enough food to feed its people), a lack of food sovereignty (the ability of an individual nation to control its own food system), and ultimately, a lack of food security.

Here’s why: As industrialization and farm subsidies enabled (mostly American) farmers to produce vast surpluses of wheat, corn, and soybeans, the global marketplace was flooded with cheap food from the developed world. Farmers in countries like Burkina Faso could not compete with such cheap and plentiful food imports—plagued as they were by land degradation (drought, soil erosion, water shortages) and armed conflict (violent clashes destroy existing crops and prevent new ones from being planted).

So they converted much of their farmable land to cash crops like coffee and cocoa. Rather than feed local populations, these commodities are exported for profit (which is usually held by those in power). Thus a system where grain was locally produced and supplied gave way to a system where it was imported from thousands of miles away. And as they became dependent on food imports, developing countries found themselves at the mercy of forces far beyond their own borders.

cash crops

Food and fiber crops grown to sell for profit rather than for use by local families or communities.

KEY CONCEPT 16.3

In less developed countries, converting farmland that once grew food for local communities to cash crop agriculture reduces the food self-sufficiency and the food sovereignty of the country.

And so it was that by 2008, Australian droughts and American agricultural policies had left the people of West Africa to riot in the streets for want of bread. We are indeed making enough food to feed the world. We just aren’t getting it to the people who need it most.

Into this morass an additional 3 billion people will soon be born. Global population is expected to reach 10 billion by 2050; experts say that to feed that many mouths, we will need to produce twice as much food as we are now producing. That will mean either farming more land or devising more production-boosting technologies. To farm more would mean clearing more forests, and thus destroying more natural habitats, species, and ecosystem services—a dire prescription at a time when the planet is already flirting with ecological disaster. How then, will we make enough food to feed the future?