Mimicking natural ecosystems can make farms more productive and help address some environmental problems.

Takao Furuno was, by most standards, a very successful industrial rice farmer, with annual yields among the highest in southern Japan. But it was a tough grind. Each year he was forced to put all his earnings back into the next year’s crop—insecticides, herbicides, irrigation, and fertilizer—so that despite his success, he and his family were left with very little for themselves at the end of each season.

KEY CONCEPT 17.5

Modeling a farm after an ecosystem (agroecology) to include a variety of plants and animals can boost productivity and protect or even enhance the local environment.

In searching for a better way, he turned, as he often did, to his forebears to see what he could learn from their knowledge. He was surprised to discover that they used to keep ducks in their rice paddies. Like most other rice farmers, Furuno considered ducks a pest, albeit a slightly cuter one than the azolla. Adult ducks eat rice seeds before they have a chance to grow, and as they forage, they trample young seedlings into the mud. This disturbance creates open patches of water, which in turn invites more ducks. “If you’re not careful, you end up with a big problem pretty quickly,” says Raquel.

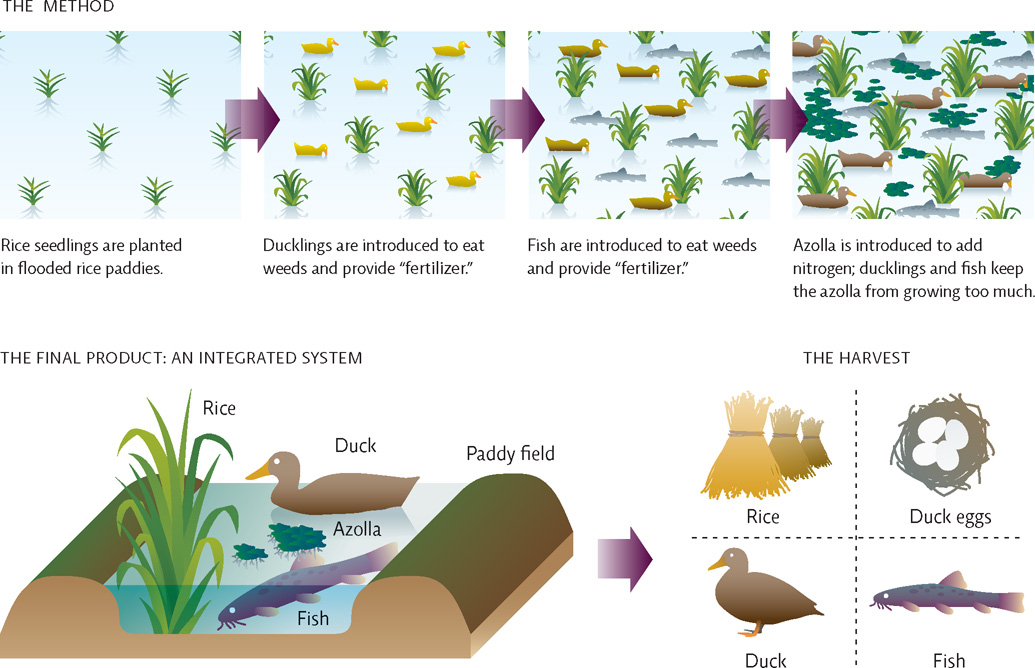

But ducklings, Furuno soon realized, were too small to do such damage; for one thing, their bills were not big or strong enough to extract seeds from mud. Instead, they ate bugs and weeds. Azolla was one of their favorites.

Furuno’s forbears also grew loaches—a type of fish—in their paddies. The loaches would also eat azolla and could be harvested and sold as food.

Together the ducklings and loaches would keep the weed from strangling the rice crop; but they would not completely eliminate the azolla the way a heavy dose of pesticides would. Furuno quickly discovered that, when kept at this benign concentration, the azolla (which contains symbiotic bacteria that produce a usable form of nitrogen) actually fertilized the rice. In fact, between the nitrogen from the azolla and the duck and fish droppings, he soon found that he no longer needed to spend money on synthetic fertilizer.

When raising ducks, fish, and rice crops together, Furuno discovered that the root crowns (where the root meets the stem) of rice plants increased to about twice the size that they had been in his old industrial system. A larger root crown meant more rice. “We’re not exactly sure why the crowns grew,” Furuno told an audience of American farmers at a recent convention in Iowa. “But the ducks seem to actually change the way the rice grows. It’s got something to do with the synergy of the whole system.” Furuno’s operation is an elegant example of biomimicry—a farm operating like a natural ecosystem. This type of farming, known as agroecology, considers both ecological concepts (modeling a farm after an ecosystem) and the value of traditional farming. INFOGRAPHIC 17.4

agroecology

A scientific field that considers the area’s ecology and indigenous knowledge and favors agricultural methods that protect the environment and meet the needs of local people.

Takao Furuno’s farm is a self-regulating, multiple-species system that naturally meets the needs of the farm ecosystem. All of the species play a role in the system, helping each other and boosting overall production.

What normal industrial inputs can be averted by growing rice using the duck/rice farm model?

No synthetic fertilizers are needed since ducks, fish, and azolla all provide nutrients. Pesticides are not needed since ducks and fish eat insect pests and weeds.

There were other financial gains, too. Duck eggs, duck meat, and fish all fetched a good price in the market. And because he was no longer using pesticides, Furuno could also grow fruit on the edges of his rice field. (He opted for fig trees, as he could harvest the figs annually without having to replant.)

Furuno’s farm is an example of polyculture—intentionally raising more than one species on a given plot of land. In the decade and a half since Furuno began duck/rice farming, his rice yields have increased by 20–50%, making his among the most productive farms in the world, nearly twice as productive as conventional farms. This kind of success is especially important for farmers in many developing countries, who struggle to produce enough food for current populations. Increasing production with lesser dependence on expensive inputs and using methods that enhance rather than diminish environmental quality can help communities become more self-sufficient and help them achieve food security (see Chapter 16).

polyculture

A farming method in which a mix of different species are grown together in one area.

The Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, which has evaluated Furuno’s method and independently verified his success, recommends the technique to Bangladeshi farmers. And by now, some 10,000 Japanese farmers have followed Furuno’s lead; his method is also catching on in China, the Philippines, and California.

Furuno’s method of duck/rice farming looked promising to the Massas. Not only would the rice plants rely on natural fertilizers and natural pest control, but the duck eggs and meat produced would be more humanely grown than those produced by factory farms. The ducks would grow up in ponds, not crammed together on slats in a barn without access to swimming water. They would get to splash around and express their “duckiness,” as Raquel puts it.

When the ducks first arrived on the Massa farm, they were just 24 hours old, cotton-ball-sized tufts of yellow feathers. The Massa children cared for them in wooden crates in their barn. But as Raquel soon learned, small ducklings grow mighty quickly. In just 2 weeks, they were large enough to turn loose. Furuno had advised stocking about 100 ducklings per acre, but Greg and Raquel did not want to sacrifice that much land for this first attempt, so they fenced off just 1,000 square meters (a quarter acre) instead. This amount of space provided plenty of room for their 120 ducklings to swim and forage but, as it turned out, not enough food to support them. “They quickly ate all the weeds in the field,” says Greg. They also trampled some of the rice plants in their pond because their section of the field was too small. But even as they ran out of weeds to eat, the baby ducks stayed away from the rice plants, just as Furuno had insisted they would.