Consumers also have a role to play in helping to bring about a sustainable food system.

In rice farming, the Massas saw a chance to implement, on their own land, all the concepts and theories they had learned as ecology students and refined and discussed as scientists. “We wanted a farm where success was measured not just in crop yield, but in the overall health of the land,” Greg says. “A place where we would count profits, but we would also count the number of sandhill cranes and California quail we saw populating the area.”

To achieve their goals, the Massas installed a recirculation system to reclaim and reuse irrigation water. They planted native oak trees along field borders to serve as a natural windbreak (windbreaks prevent soil from being carried away by wind erosion), and they installed nest boxes for wood ducks, barn owls, and bats so that those wild animals would keep area pests in check. “The idea was to restore as much of the natural biodiversity as possible,” says Greg, “so that we would not need artificial inputs to run the system.” They also took their sustainable ideals to the next level and built a straw house to live in—made of 2-foot-thick (0.5 meters) walls of rice bale, coated on both sides with plastic or stucco—that can withstand the unforgiving heat of a Chico summer and maintain a steady temperature almost entirely by itself. The house is fireproof, rodent proof, and, as Greg likes to joke, bulletproof, too.

The Massas also wanted to create a farm that contributed to the formation of a local community food system; they planned to sell a portion of their rice at local outlets like farmers’ markets and food co-ops. More and more consumers are buying food from local farmers; local agriculture supports local economies and provides fresher and thus healthier food to consumers. Because transportation depends on fossil fuels, the more food miles a product travels before reaching the consumer, the greater the carbon footprint of that food. And much of our food has traveled quite far—about 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles), on average.

food miles

The distance a food travels from its site of production to the consumer.

carbon footprint

The amount of carbon released to the atmosphere by a person, a company, a nation, or an activity.

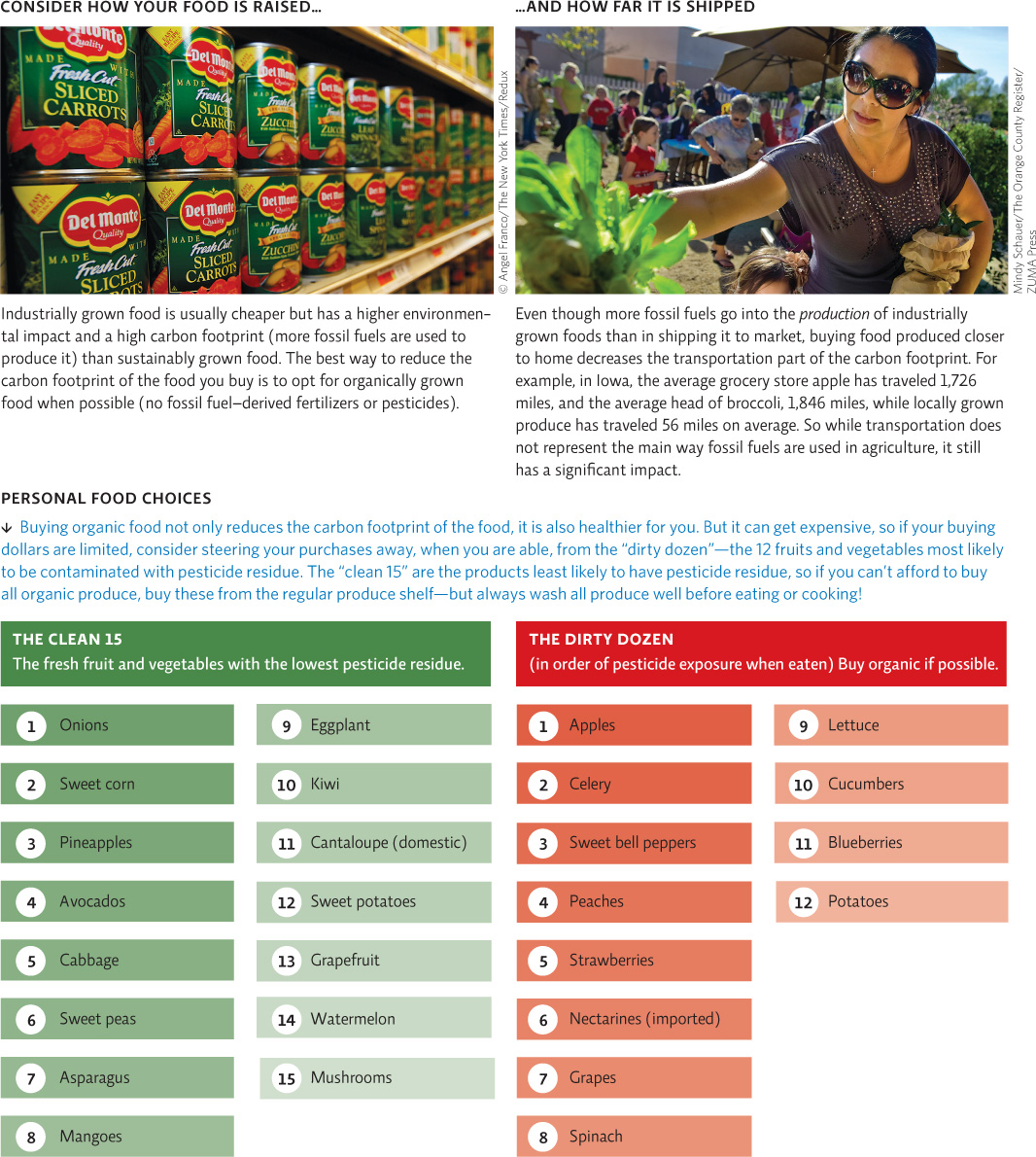

However, transportation is not the main use of fossil fuels when crops are raised industrially. Research by Christopher Weber and Scott Matthews of Carnegie Mellon University determined that about 90% of the carbon footprint for food grown using conventional industrial methods is from the production of the crop (fuel for equipment, raw materials for pesticides and fertilizer production), not its transport. Therefore, buying organically grown produce—even from far away—may reduce the carbon footprint more so than buying locally grown industrial crops. Of course, the best option is to choose organic foods that are locally grown. Likewise, because beef raised in industrial CAFOs has one of the highest carbon footprints of all agricultural products (see LaunchPad Chapter 30), one of the best things you can do is to replace at least some of the beef you eat with chicken, pork, fish, or meatless dishes.

KEY CONCEPT 17.8

Consumers can support sustainable agriculture with their purchases. Buying locally grown, organic food is the best option for reducing the carbon footprint of that food.

Consumers are becoming more aware that things like food miles and the way food is raised matter for the environment, their communities, and their own health. Organic foods and ethically raised animal products are claiming a bigger share of consumer dollars annually. But this has opened the door to greenwashing—making claims about the environmental benefits of sustainably raised or organic foods that are misleading. (For example, organic cookies are probably not really healthier than those made with conventional ingredients, and “cage-free” eggs may still be from chickens living in overcrowded conditions.) Consumers need to be diligent about evaluating claims and make informed decisions about what to purchase. INFOGRAPHIC 17.7

greenwashing

Claiming environmental benefits about a product when the benefits are actually minor or nonexistent.

Because the growing and transport of our food impacts the environment and our own health so much, choosing foods produced in a way that has a lower impact makes a difference. This also supports sustainable agriculture as an economic endeavor, helping the farmers and communities pursuing these methods.

© Angel Franco/The New York Times/Redux

Mindy Schauer/The Orange County Register/ZUMA Press

What information would you like to see on food labels that would allow you to make wise consumer choices when buying food? Does food labeling need to be regulated so that certain terms (e.g., organic, free range) is specifically defined?

Answers will vary but might include things like country or even state of origin, method of growing (organic, sustainable, industrial, etc.); date it was processed or picked; expiration date, carbon footprint to produce, etc. Regulation of labels makes it easier for consumers to really know what they are getting. Unregulated terminology is meaningless and can be used to confuse or sway the consumer (greenwashing).