Mining comes with a set of serious trade-offs.

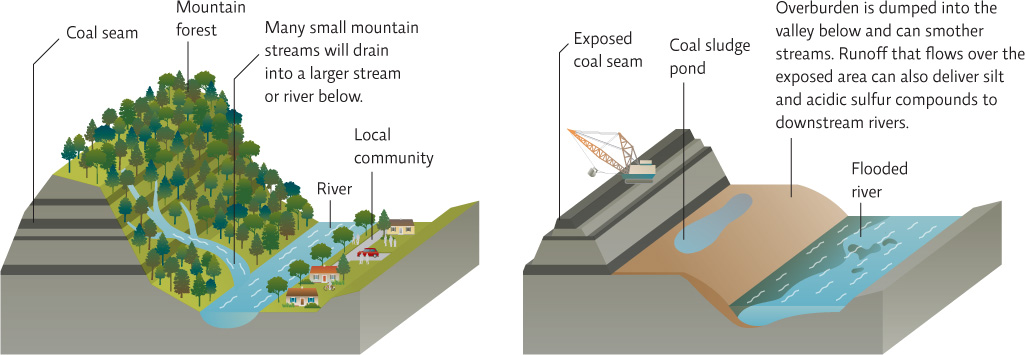

Hobet 21, which has claimed at least 5,000 hectares (12,000 acres) of land, was once the site of several adjacent peaks. To get at the coal beneath those peaks, miners began by clear-cutting the forest above. Next, they drilled holes deep into the side of the mountain (some holes up to 120 meters [400 feet] deep), set dynamite in those holes, and blasted as much as 300 meters (1,000 feet) of mountain into a mass of rubble known as overburden. The miners repeated this process several times, until the layers of coal were exposed. Then, using buckets big enough to hold 20 midsized cars, they scooped that rubble into staircase-shaped mounds that filled in entire neighboring valleys from the ground up—all told some 72 million metric tons (80 million U.S. tons) of overburden each year. The process obliterated the forest habitat, buried countless streams, and permanently reordered the land’s natural contours. INFOGRAPHIC 18.4

Surface mining techniques are used when coal seams are close to the surface, or in the case of Appalachia, when the coal seams are thin and can’t be efficiently accessed via subsurface mining. In Appalachia, the forests are first clear-cut and then explosives are used to blast away part of the mountain. Heavy equipment then digs through debris, dumping the overburden (soil and rock) into the nearby valley, burying streams as the valley is filled in. The exposed coal is dug out and some processing is done on site. Coal sludge left over from processing is stored in ponds on the mining site.

Why is the overburden dumped into the valley below when it is known that it damages streams and valley habitat?

Where else would it go? It is expensive to haul the overburden to another distant site so the mining operation chooses to dump it over the edge of the work area, into the valley below.

overburden

The rock and soil removed to uncover a mineral deposit during surface mining.

KEY CONCEPT 18.4

Mountaintop removal is a cost-effective surface mining method used to obtain coal, but it creates tremendous environmental damage and employs fewer miners than other methods.

This mountaintop removal mining is just one form of surface mining. The other type, known as strip mining, employs a similar process: Workers use heavy equipment to remove and set aside overburden so that they can harvest the coal beneath. When they finish mining one strip of land, they return the overburden to the open pit and move on to a new strip. Strip mines are used in areas like Wyoming, where the coal is close to the surface and the ground above is fairly level.

surface mining

A form of mining that involves removing soil and rock that overlays a mineral deposit close to the surface in order to access that deposit.

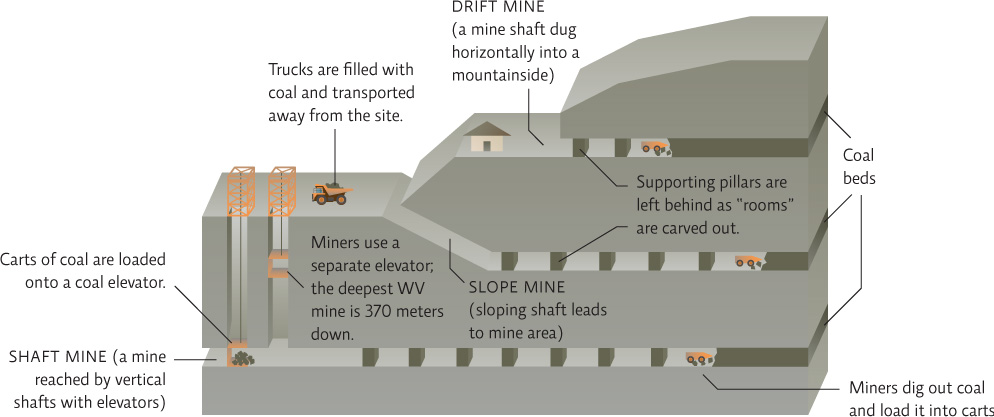

With their reliance on explosives and heavy equipment, surface mines are a far cry from the underground mines, also called subsurface mines, that sustained the Nelson family for so many generations. “When our daddies were mining, back in the ‘40s and ‘50s, the seams were as tall as full-grown men,” says Nelson, who since retiring has become a spokesperson for the anti-mining Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition. “So you could get at ‘em the old-fashioned way, with pickaxes and sledgehammers.” Those days of plenty are gone, he says. Many of the coal seams that remain are too thin to be culled by human hands.

subsurface mines

Sites where tunnels are dug underground to access mineral resources.

To be sure, subsurface mines (which still make up about 60% of all coal mines worldwide, and about 50% of those in the United States) come with their own challenges. Water seeps easily into tunnels, and as it does, toxins leach from the surrounding rocks into the gathering pools. Sulfate in particular produces acid mine drainage, which goes on to contaminate soil and streams and has become a major problem with both active and closed mines. In 2011, Duke University ecologist Emily Bernhardt and her colleagues reported that not only is acidic water directly toxic to many aquatic plants and animals, it also alters the nutrient cycle of streams in ways that reverberate all the way up the food chain. Subsurface mines also account for 10% of all methane release in the United States; methane is a potent greenhouse gas. INFOGRAPHIC 18.5

acid mine drainage

Water that flows past exposed rock in mines and leaches out sulfates. These sulfates react with the water and oxygen to form acids (low-pH solutions).

Subsurface mines are used to access large deposits or thick seams of many minerals and ores, including coal. Modern mining depends on powerful machinery to drill out tunnels and remove and transport the materials.

Why isn’t the coal found in the regions where mountaintop removal is used removed with subsurface mining instead?

The coal in these areas occurs in thinner seams that makes it inefficient and unreasonable to try and remove it with traditional subsurface mining techniques.

KEY CONCEPT 18.5

Subsurface mining is used to access deep, thick coal seams. It is less environmentally damaging and employs more workers than surface mining but is a hazardous job.

But subsurface mines also come with some advantages. Unlike surface mines, they don’t disrupt or permanently alter large surface areas. And because much of the work is still done with workers rather than by machines, they employ more people. In Appalachia, 100,000 mining jobs were lost between 1980 and 1993 as underground mining gave way to mountaintop removal. In Kentucky alone, mining jobs are down 60% in recent years, even though coal production is on an upswing. The loss of traditional mining jobs has bred yet another controversy in the region. Coal industry reps say that the riskier deep-mining jobs are being replaced with higher-paying, safer work—like demolition and heavy equipment operation. But that has not alleviated tension as more jobs are lost than replaced. “It’s a double insult,” says Tim Landry, a fourth-generation deep miner in West Virginia. “They’re not only destroying the land that we love, but they’re taking our jobs away, too.”

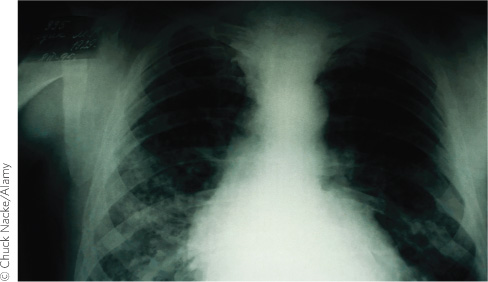

MINING HAZARDS

KEY CONCEPT 18.6

Coal is a valuable fuel, but coal mining creates significant environmental and health problems for workers, community members, and the local ecosystem.

But a loss of jobs is not the community’s only—or even its most serious—concern.