Fossil fuels are a valuable, but nonrenewable, resource.

KEY CONCEPT 19.1

Fossil fuels form when organic matter is buried and subjected to high temperature and pressure. Because we use them much faster than they form, they are considered nonrenewable resources.

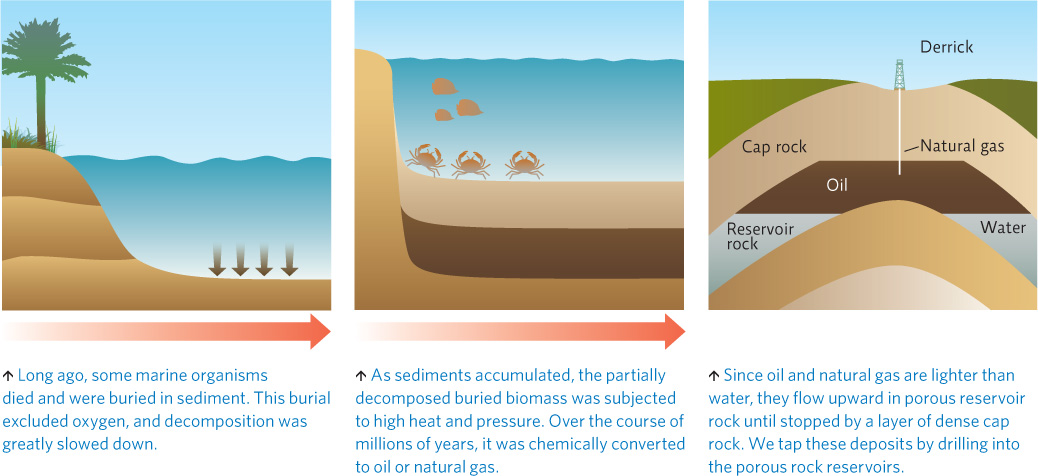

Fossil fuels form over millions of years when organisms die and are buried in sediment under conditions that slow down decomposition tremendously. In time, as pressure and heat increase, the buried material goes through a chemical transformation to form oil, natural gas, or coal. (See Chapter 18 for more on coal.) Even though they are produced by natural processes, fossil fuels are considered a nonrenewable resource because we are using them up in a fraction of the time it takes for them to form. In other words, natural processes cannot possibly keep pace with human consumption. INFOGRAPHIC 19.1

fossil fuel

A variety of hydrocarbons formed from the remains of dead organisms.

oil

A liquid fossil fuel useful as a fuel or as a raw material for industrial products.

natural gas

A gaseous fossil fuel composed mainly of simpler hydrocarbons, mostly methane.

nonrenewable resource

A resource that is formed more slowly than it is used or that is present in a finite supply.

How is the formation of oil and natural gas similar to and different from the formation of coal? (See Infographic 18.2.)

All three are formed from dead organic material that was buried before it could completely decay and was converted to its final form from the high heat and pressures of deep burial under sediments. They differ in their starting material: Coal was formed from plant material, whereas oil and natural gas where formed from marine organisms

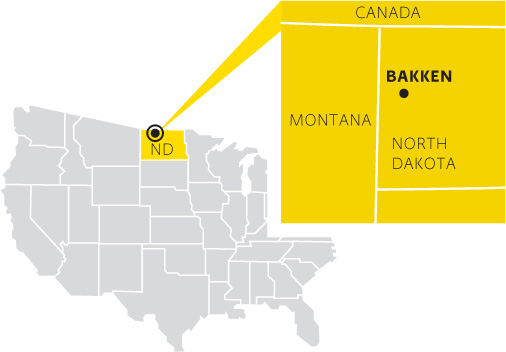

Everywhere, countries are looking for new sources of oil. The heart of this U.S. oil boom is the Bakken formation, a roughly 500,000-square-kilometer (200,000-square-mile) shale formation deep underground that resides mostly in North Dakota but also stretches westward into Montana and north into the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. (Shale is a type of sedimentary rock that is very dense and does not easily let the oil and natural gas trapped within escape.) It’s the largest continuous oil accumulation the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has ever assessed. And according to the agency, it contains as much as 167 billion barrels of crude oil in the North Dakota portion alone; the entire formation contains perhaps 400 billion barrels. (A barrel of oil is equivalent to 159 liters, or 42 gallons.) The United States has other oil-rich shale formations, including the highly productive Eagle Ford formation in Texas. Together, Bakken and Eagle Ford produced 96% of all U.S. shale oil in 2012.

How many of the barrels at Bakken can actually be harvested has been a matter of intense speculation. Bakken oil is made up almost exclusively of tight oil—shale oil that’s trapped inside impermeable rock deposits. Tight oil is difficult to access not only because the oil is trapped inside rock but because the deposits themselves tend to be buried very deep—thousands of meters below ground, in many cases. It also tends to be widely dispersed throughout the rock. In 2013, the USGS estimated that 7.4 billion barrels could be recovered from the Bakken oil fields, largely thanks to fracking (hydraulic fracturing)—a drilling technique that involves detonating explosive charges to create fractures in the rock and then injecting mass quantities of a highly pressurized water and chemical mixture into the factures to liberate the oil (and/or natural gas) trapped inside.

tight oil

Light (low-density) oil in shale rock deposits of very low permeability; extracted by fracking.

fracking (hydraulic fracturing)

The extraction of oil or natural gas from dense rock formations by creating factures in the rock and then flushing out the oil/gas with pressurized fluid.

In 2014, roughly 1 million barrels of crude oil were being recovered each day from Bakken via fracking. That’s not much in the grand scheme of things: In 2013 the United States consumed almost 19 million barrels of oil daily. But in the short term, experts say, fracking has transformed the domestic energy debate. As of 2013, the Bakken oil field was producing more than 10% of all oil produced in the United States, and North Dakota had gone from being the nation’s ninth-largest oil producer to being its second, right after Texas. As a result, its unemployment rate had dropped precipitously, to around 1%.

But booms tend to be mixed blessings at best, and the fracking boom is no exception. In and around the cities close to the Bakken oil fields, such as Williston, North Dakota, economic gains on the one hand have come at the expense of rampant housing shortages, rising crime, and environmental degradation on the other. Fracking is water intensive and requires a blend of toxic chemicals to work properly. Area residents can’t help but worry about their drinking water, not to mention the air and soil quality around drilling sites. They also worry about their way of life: Can a regional culture built on solitude and serenity survive the boom, not to mention the bust that will inevitably follow?

And those concerns now echo across a nation, as oil and natural gas reserves from North Dakota to Texas to Pennsylvania are harvested using fracking technology. “The implications are already reverberating far beyond North Dakota,” National Geographic wrote in 2013. “Bakken-like shale formations occur across the United States, indeed, across the world. The extraction technology refined here is in effect a skeleton key that can be used to open other fossil fuel treasure chests.”