The Greenland Vikings’ demise was caused by natural events and human choices.

Greenland’s interior is covered by vast ice sheets that stretch toward the horizon—3,000 meters (10,000 feet) thick and more than 250,000 years old. To residents of the hard land, these ice sheets are not good for much— they create harsh winds and brutal cold—but to climate scientists, they’re a treasure trove. As snow falls, it absorbs various particles from the atmosphere and lands on the ice sheets. As time passes, the snow and particles compact into ice, freezing in time perfect samples of the atmosphere as it existed when that snow first fell. By analyzing those ice-trapped particles—dust, gases, chemicals, even the water molecules—scientists can get a pretty good idea of what was happening to the climate at any given time. “It’s like perfectly preserved slices of atmosphere from the past,” says Lisa Barlow, a geologist and climate researcher at the University of Colorado at Boulder. “It gives us additional clues as to what was going on.”

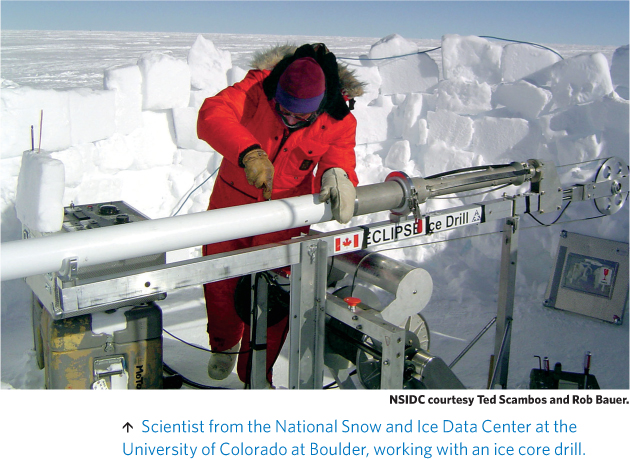

To uncover those clues, a team of scientists and engineers picked an accessible segment of ice sheet, not far from the Viking settlements, drilled from the surface all the way down to the bedrock below, and extracted a 12-centimeter-wide (5-inch-wide), 3,000-meter-long cylinder of ice, which they then divided and dispersed among a handful of labs around the globe, including Jim White’s light stable isotope lab—also at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Analysis of thin sequential segments of the ice core showed that when the Vikings first arrived in Greenland, the temperature was anomalously higher than the average over the preceding 1,000 years. (Atmospheric temperature can be deduced from the amount of oxygen-18 or deuterium—heavy hydrogen—present in the sample.) By the time the Vikings had vanished, temperatures had lowered so much that scientists call the period the Little Ice Age—a time when all the seasons were cooler than normal and winters were exceptionally cold. “It’s no wonder they didn’t make it,” says Barlow. “With lower temperatures, livestock would have starved for lack of hay over the long winter, and self-inflicted environmental damage made the situation worse.”

Indeed, in addition to natural climate change (Diamond’s first factor), the Vikings also suffered from self-inflicted environmental damage (Diamond’s second factor).

In addition to that single ice core, scientists have analyzed hundreds of mud cores taken from lake beds around the Viking settlements. These mud samples—which contain large amounts of soil that was blown into the lakes during Viking times—indicate that soil erosion had become a significant problem long before the region descended into a mini ice age. “This wasn’t a climate problem,” says Bent Fredskild, a Danish scientist who extracted and studied many of the mud cores. “This was self-inflicted. It happened the same way that soil erosion happens today— they overgrazed the land, and once it was denuded, there was nothing to anchor the soil in place. So the wind carried it away.”

Overgrazing wasn’t their only mistake. The Greenland Vikings also used grassland to insulate their houses against the cold of winter; typical insulation consisted of 2-meter-thick (about 6 feet) slabs of turf, and a typical home took about 4 hectares (10 acres) of grassland to insulate. On top of that, they chopped down the forests, harvesting enough timber to not only provide fuel and build houses but also to make the innumerable wooden objects to which they had become accustomed back in Norway.

Greenland’s ecosystem was far too fragile to endure such pressure, especially as the settlement grew from a few hundred to a few thousand. The short, cool growing season meant that plants developed slowly, which in turn meant that the land could not recover quickly enough from the various assaults to protect the soil.

As climate cooling and overharvesting conspired to destroy pasturelands, summer hay yields shrank. When scientists counted the fossilized remains of insects that lived in the fields and haylofts of Viking Greenland, they found that their numbers fell dramatically in the settlement’s final years. “The falloff in insects tells us that hay production dwindled to the point of crisis,” said the late Peter Skidmore, a Sheffield University entomologist. Without hay, livestock could not survive the ever-colder, ever-longer winters. And without livestock, the Vikings themselves went hungry. As scientists have discovered, they needn’t have.