We have several options for addressing air pollution.

Solutions such as installing better ventilation systems in our homes and providing solar ovens to individuals in developing countries will help address indoor air pollution, but outdoor air pollution requires a more regional, national, and even international approach. Since air pollution often travels to areas that do not produce significant amounts of pollution themselves, regulating air pollution is a particular challenge. How does one country regulate pollution that travels through the atmosphere from another country?

In developed countries, the original approach to dealing with air pollution from human activities was to spread it out; the slogan was “The solution to pollution is dilution.” Factories, power plants, and other point sources built tall smokestacks to send emissions high into the atmosphere so that they wouldn’t pool at the site of production. The idea was that if dispersed, the amount of pollution in any one area would be too low to cause a problem. But this approach simply doesn’t work: Industry releases too much pollution, and air circulation patterns cause some areas to get more than their share of pollution.

Eventually it became clear that regulation would be necessary. The typical approach in the 1970s was command-and-control regulation, a type of regulation that involves setting national limits on how much pollution can be released into the environment and imposes fines or even brings criminal charges against violators who release more than is allowed. An example of command-and-control regulation in the United States is the Clean Air Act (CAA). It sets a maximum amount, or air quality standard, for emissions of pollutants or for the presence of pollutants in ambient air. States are responsible for monitoring air quality as well as for developing, implementing, and enforcing compliance plans approved by the EPA. As a result of the CAA, the United States has seen major reductions in common air pollutants. Removing lead from gasoline, for instance, reduced lead air pollution by 98% from 1970 levels. Sulfur pollution has also been significantly reduced. And the Mercury and Air Toxic Standards approved in 2011, which limit the release of mercury, acid gases, and other pollutants from power plants, are expected to prevent 130,000 cases of serious asthma and as many as 11,000 premature deaths annually.

command-and-control

A type of regulation that involves setting an upper allowable limit of pollution release that is enforced with fines and/or incarceration.

Clean Air Act (CAA)

First passed in 1963 and amended in 1990, a U.S. law that authorizes the EPA to set standards for dangerous air pollutants and enforce those standards.

The CAA is, however, now under attack. Because regulation is based on legislation, it is subject to political wrangling; several congressional bills have been introduced that would limit the EPA’s ability to regulate air quality. Of particular concern right now is the regulation of carbon dioxide (CO2). Although it is naturally occurring, and previously considered harmless, CO2 has now been strongly linked to climate change (see Chapter 21). In a landmark case, the Supreme Court gave the EPA the authority to regulate CO2 as a pollutant in 2007, but the EPA immediately faced political opposition. In 2010, the EPA approved greenhouse gas emission standards (including CO2, methane, and N2O) for light-duty vehicles (cars and trucks) that require new vehicles to produce less greenhouse gas emissions; the government started phasing in these new regulations in 2012, and will continue to do so until 2016.

Setting new U.S. standards for coal-fired power plants or other large CO2 emitters is proving more difficult as these regulations are strongly opposed by the coal industry and others. The EPA proposed the Clean Power Plan in June 2014, setting a goal for cutting carbon emissions from power plants by 30% by 2030. In July 2014, the Supreme Court ruled that the EPA cannot require new facilities whose only pollution emissions would be CO2 to obtain CO2 permits; however, the Court upheld the EPA’s ability to require any existing facility that already must acquire permits for emissions for other pollutants to also obtain permits for CO2 emissions. The EPA hopes to have a regulatory plan in place by June 2016.

KEY CONCEPT 20.9

Cleaner fuels and smokestack scrubbers can reduce industrial air pollution. Regulations and economic incentives can spur innovation but may raise the cost of providing energy or doing business.

The fact that our air is cleaner today than it was in the 1960s—even with a larger U.S. population and more industry—is evidence that regulations can be effective. Still, these improvements are costly to industry, and such costs are usually passed on to consumers. For this reason, many individuals and groups oppose such policies, charging that the restrictions are excessive or that the government goes too far in trying to regulate emissions. Some environmentalists worry that if we weaken or dismantle the environmental legislation that protects our air and water (and, by extension, our health and ecosystems), we face the return of a highly contaminated environment, compromised health, and diminished ecosystem function and services.

In addition to command-and-control regulation, there are other ways to curb pollution. One example is green taxes on environmentally undesirable actions, such as an extra tax on low-mile-per-gallon vehicles. Tax credits, reductions in the amount of tax one pays in exchange for environmentally beneficial actions, fall on the other side of the spectrum. Tax credits encourage consumers to pursue options that might be more expensive than conventional options (such as the purchase of a hybrid automobile). As more people buy the products, the industries that make them can scale up and bring down prices.

green tax

A tax (fee paid to government) assessed on environmentally undesirable activities.

tax credit

A reduction in the tax one must pay in exchange for some desirable action.

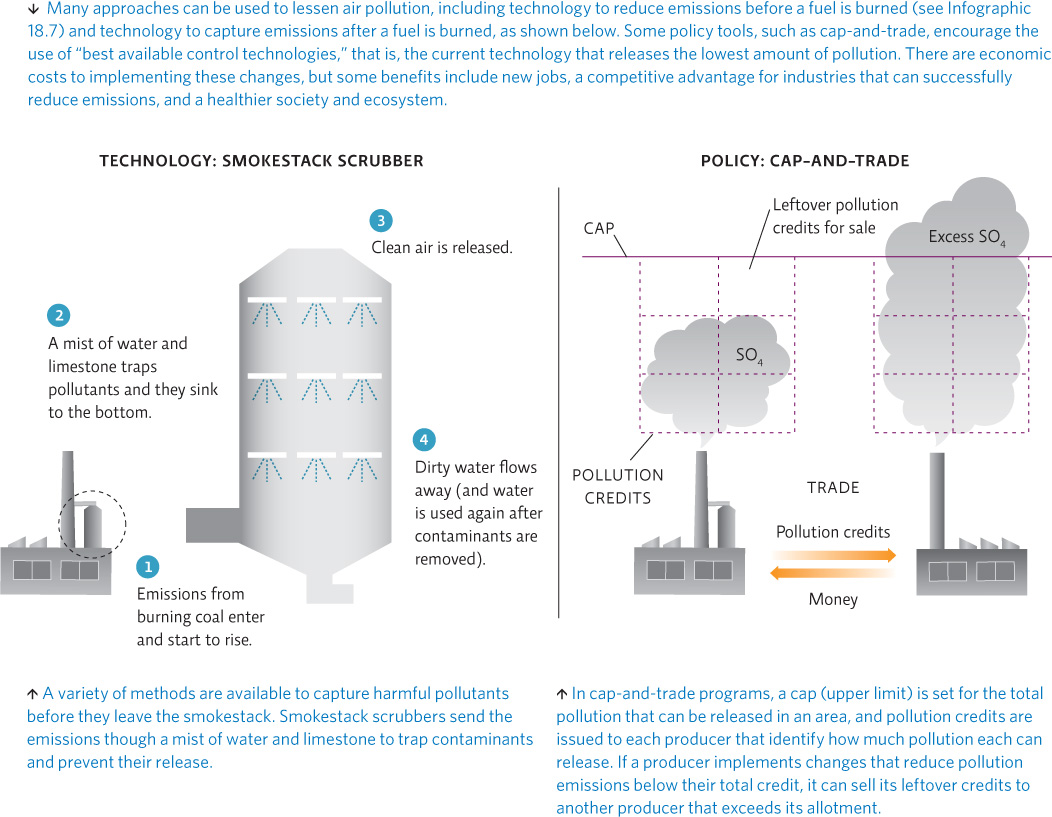

Governments also offer subsidies, free money or resources intended to promote environmentally friendly activities. And with cap-and-trade, also called permit trading, a government or regulatory agency sets an upper limit on emissions for a pollutant on a nationwide or regional level and then gives or sells permits to polluting industries. Users that reduce their pollution emissions below what their permit allows can sell their remaining credits to other users that exceed their allotments. Over time, pollution levels can be reduced as the cap—or limit—is lowered. A cap-and-trade program successfully reduced sulfur pollution from coal-fired power plants in the United States in the 1990s. A downside to cap-and-trade programs is that pollution can become concentrated in areas where industries choose to buy additional permits rather than reduce emissions.

subsidies

Financial assistance given by the government to promote desired activities.

cap-and-trade

Regulations that set an upper limit for pollution emissions, issue permits to producers for a portion of that amount, and allow producers that release less than their allotment to sell permits to those who exceeded their allotment.

Technology can also play a big role in improving air quality. To improve indoor air quality, we can install air filters and better ventilation systems. To curb pollution emissions from manufacturing, we can use end-of-pipe solutions like scrubbers, filters, electrostatic precipitators, and catalytic converters to trap pollutants before they are released. In addition, technology can inspire cleaner methods for extracting energy out of fossil fuels, as is the case with “clean coal” technologies described in Chapter 18. INFOGRAPHIC 20.6

How could a cap-and-trade program for sulfur pollution lead to lower pollution in one area and higher pollution in others?

In an area where pollution is decreased below the amount allowed, pollution levels will decrease but in areas that have industries that choose to buy pollution credits rather than lower pollution, air pollution would be greater.

Mitigating or preventing air pollution costs money, but many feel it is money well spent because it prevents far greater losses down the line—especially in terms of human health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that, in 2007, the cost of asthma to the United States was $56 billion. According to a 2003 study published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the average annual cost of care for an asthma patient is $4,912, with 65% of that going to medications, hospital admissions, and nonemergency doctor visits. The remaining 35% goes to indirect costs like lost time at work. Nadeau, Delfino, and others hope their research helps policy makers realize just how useful curbing air pollution can be. “We’re talking about the air we breathe,” Thurston says. “There’s nothing more communal than that.”

Select References:

Cisternas, M. et al., (2003). A comprehensive study of the direct and indirect costs of adult asthma. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 111(6): 1212–1218.

Delfino, R. J., et al. (2008). Traffic-related air pollution and asthma onset in children: A prospective cohort study with individual exposure measurement. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(10): 550–558.

Dockery, D., et al. (1993). An association between air pollution and mortality in six US cities. New England Journal of Medicine, 329(24): 1753–1759.

Laden, F., et al. (2006). Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality, extended follow-up of the Harvard Six Cities Study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 173(6): 667–672.

Morello-Frosch, R., et al. (2002). Environmental justice and regional inequality in southern California: Implications for future research. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110(2): 149–154.

Nadeau, K., et al. (2010). Ambient air pollution impairs regulatory T-cell function in asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 126(4): 845–852.

Runyon, R. S., et al. (2012). Asthma discordance in twins is linked to epigenetic modifications of T cells. PloS ONE, 7(11): e48796.

Spira-Cohen, A., et al. (2011). Personal exposures to traffic-related air pollution and acute respiratory health among Bronx schoolchildren with asthma. Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(4): 559–565.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Individuals can have an effect on air quality by researching the threats to their area, making appropriate behavior changes, and supporting legislation that limits the production of air pollutants.

Individual Steps

•Reduce your exposure to indoor air pollution by reducing your use of harsh cleaning products, synthetic air fresheners, vinyl products, and oil-based candles.

•Avoid outdoor exercise during poor air quality days. Go to http://airnow.gov to find the local air quality forecast.

•Buy a radon detector and carbon monoxide detector for your house to keep your family safe.

Group Action

•Organize a “car-free day” at your school, community, or workplace to reduce emissions from vehicles.

•Work with community leaders and businesses to sponsor a “free public transit” day.

Policy Change

•If your community does not have public transit, ask community leaders to investigate bringing it to your area.

•Many groups are working to improve our air quality. Find one in your region and see what issues it is addressing. For a list of national and regional organizations, go to www.inspirationgreen.com/air.